Even as the dust settles from the Oct. 28 parliamentary election, Ukraine’s economic challenges remain stubbornly the same: fiscal imbalances, growing pressure on the hryvnia and a global slowdown.

But parliament’s latest decision – to authorize the mandatory resale of up to half of banks’ foreign currency proceeds – shows the strategy hasn’t changed, even if the Verkhovna Rada’s composition will.

During the run-up to the fall election, Ukraine’s business climate was plagued by a toxic mixture of uncertainty and worsening economic conditions.

Some took comfort in the modest victory of the pro-presidential Party of Regions, who under President Viktor Yanukovych promised stability.

Recent weeks have seen some uplifting headlines. Ukraine jumped up 15 spots in the World Bank’s 2013 Doing Business ranking to 137, driven by improvements in the ease of starting a business, registering property and paying taxes.

Likewise, Ukraine’s main stock index, the UX, took a break from its month-long freefall, recovering 7.5 percent in three days. Abroad, Ukrainian names also rallied. Five-year credit default spreads – a rough measure of a country’s perceived risk – fell to a 13-month low.

But it’s premature to call this encouraging news. None of the country’s fundamental problems has been addressed. The economy shrank 1.3 percent in the third quarter of 2012, while steel output dropped 15 percent in October compared to last year.

Moreover, pressures on the currency are mounting.

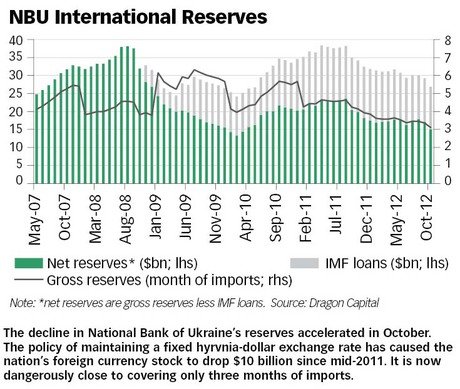

Ukrainian citizens have rushed to trade soft hryvnias for hard dollars, bringing down the National Bank of Ukraine’s international reserves by $2.4 billion in October alone.

At the end of last month, these reserves stood at $26.8 billion, the lowest level since December 2009.

“Gross international reserves are likely to continue shrinking through year end, gradually approaching the safety threshold of three months’ worth of future imports of goods and services ($24-25 billion).

This could prompt the authorities to execute exchange rate adjustment and consider changes to the current de facto fixed exchange rate regime,” investment bank Troika Dialog wrote in a note to investors.

If a current gradual depreciation strategy is pursued, the hryvnia-to-dollar exchange rate should hit 8.5 by end-2012 from the current 8.2 hryvnias per dollar, experts note.

In a move to provide relief to the hryvnia, parliament on Nov. 6 signed a bill that would authorize the National Bank of Ukraine to require banks to surrender up to half of their foreign currency proceeds for up to six months.

The restriction could be extended beyond the six months, claims opposition parliamentarian and former banker Stanyslav Arzhevitin.

If signed by Yanukovych, the forced selloff of foreign currency would bring Ukraine back to the 1998-2005 period, when such heavy-handed controls were in force.

Experts have long argued that a more flexible exchange rate would benefit the economy, boosting exports and cutting the current account deficit.

In neighboring Poland, a weaker zloty in the first half of 2012 is set to drive the country’s highest food exports in history.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian leaders mention end-2013 as a likely date for currency regime liberalization.

According to investment bank Dragon Capital, the central bank is likely to start with more modest demands of 20-30 percent selloff. Given Ukraine’s onthly export cash inflows of $8 billion, this would mean temporary gain of $1.6-$2 billion a month.

If signed by Yanukovych, the forced selloff of foreign currency would bring Ukraine back to the 1998-2005 period, when such heavy-handed controls were in force.

“The legislation should thus provide for steadier inflows of foreign currency to the interbank foreign currency market and tighten NBU control over these flows. However, if the NBU reaches the point when it can no longer withstand currency pressures, the regulation will hardly prevent abrupt devaluation,” the bank wrote in a note to investors.

Meanwhile, the global slowdown is affecting revenue collection and blowing a hole in the budget. As a result, parliament increased the central budget deficit by almost $1 billion to provide subsidies for regional heating outfits.

While this could be popular with the populace, it goes against International Monetary Fund demands to eliminate de facto gas subsidies to households as a condition of renewing a loan program.

Despite the country’s need for cash and the benefits for long-term macroeconomic stability, Ukraine’s authorities put off any such moves until after the elections.

Now that the vote has come and gone, it seems nothing in their economic strategy has changed.

Kyiv Post editor Jakub Parusinski can be reached at [email protected]