About $11.4 billion has been looted from Ukraine’s banks in recent years and Ukrainians, directly and indirectly, will be paying for the grand-scale theft for years to come.

What makes the crimes even more maddening are that the bank robbers are, for the most part, known to the authorities.

Yet no one has been convicted, let alone prosecuted, for bank fraud, and less than 10 percent of the total losses are likely to be recovered.

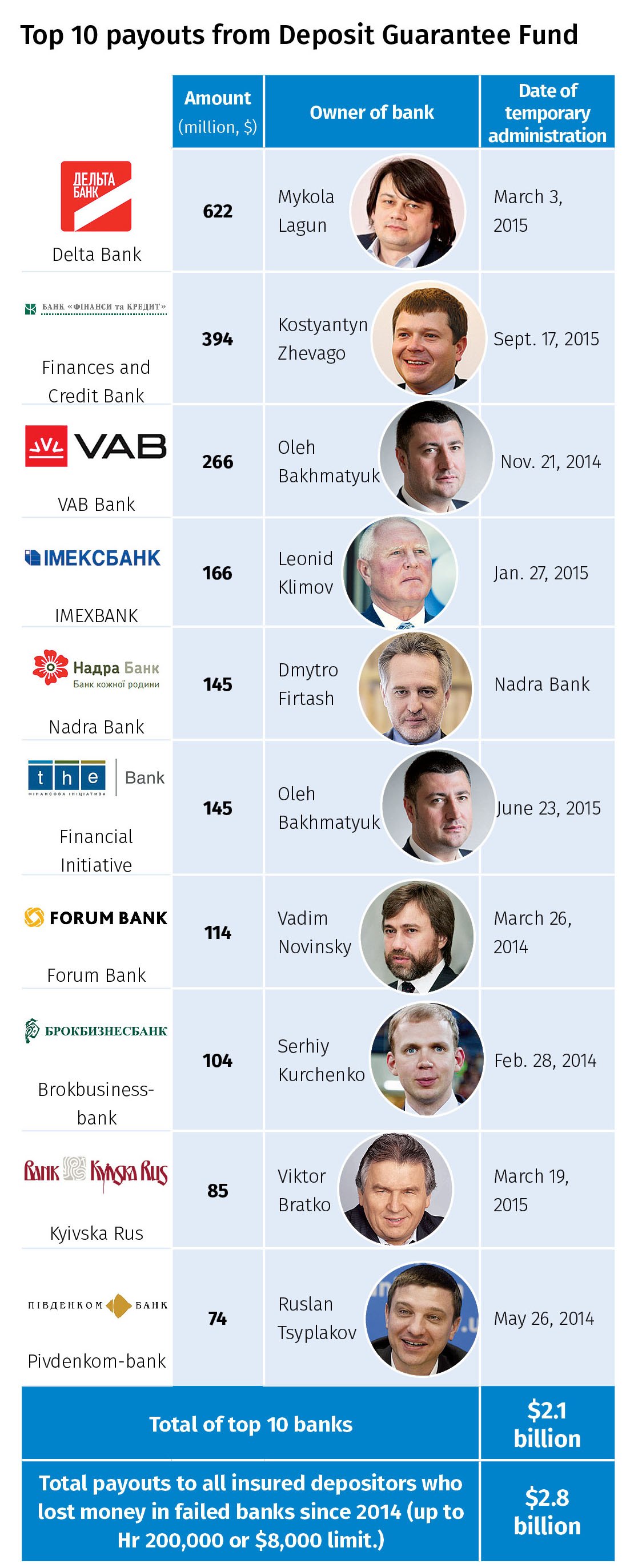

The $11.4 billion figure is made up of three parts, estimated by the National Bank of Ukraine and Deposit Guarantee Fund:

1. $3 billion paid out to insured depositors;

2. $5.2 billion in uninsured losses; and

3. $3.2 billion in loans still owed to the central bank.

The staggering sum is more than 10 percent of the nation’s expected total economic output this year of $100 billion.

‘Absolutely frustrated’

“As you mentioned correctly: absolutely no prosecution, or any court hearings about all this fraud – everything is documented and sent to our police, to our prosecutor’s office,” National Bank of Ukraine Governor Valeria Gontareva told the Kyiv Post in a June 21 interview. “We did our job properly. We sent these banks for liquidation. The Deposit Guarantee Fund sent more than 2,000 requests for our prosecutors and police.”

About the lack of results, Gontareva said, “we are absolutely frustrated about that. For us it’s a more frustrating picture than for all of our citizens because we did our job properly. We documented it properly.”

She scoffed at claims of prosecutors who, when asked to explain their inactivity, questioned the strength of the evidence of bank fraud supplied by the two major players: the central bank, which regulates the industry and declares banks insolvent, and the state-financed Deposit Guarantee Fund, which liquidates insolvent banks and repays individual depositors up to Hr 200,000 ($8,000) in state-insured losses.

“Top quality is our quality,” Gontareva said. “Everything is documented; 70 percent or 80 percent of cases are just simple fraud or money laundering. You do not need any high-quality forensic professionals. We’ve already documented all this fraud and money laundering. We could not send banks to the Deposit Guarantee Fund for liquidation or for resolution without any proof of wrongdoing.”

She said that more than 90 percent of loan portfolios in many failed banks simply involved insider lending schemes.

Corrupt courts

In the end, Gontareva said, nothing will improve substantially in Ukraine without rule of law – including independent, effective and honest police, prosecutors and judges.

“Everybody should start from the court system,” Gontareva said. “If the court will not be corrupted, all prosecution and police will start to transform themselves.”

But as for her role in this transformation, “it’s not absolutely not my responsibility, not my mandate,” Gontareva said.

She doesn’t favor the appointment of a special anti-prosecutor or legal team for bank-fraud issues and recovery of assets. She also doesn’t favor making a public registry of all bad loans in Ukraine, even in state-owned banks.

“Like a regulator, I believe that bank secrecy should be there,” she said.

Deadbeat borrowers

When claims for repayment of bad debt are made in court, as the central bank has done, the information becomes public. It is not only Ukraine’s remaining 103 banks that are infected with non-performing loans, or deadbeat borrowers.

So is the central bank.

When she took over as NBU governor in 2014, she inherited a stock of Hr 110 billion (now $4.4 billion) in unpaid refinancing loans issued to bankers stretching out over many years, not just during Viktor Yanukovych’s 2010-2014 presidency.

“The biggest part of this portfolio is the legacy of 2008,” Gontareva said. She said Hr 77 billion ($3.1 billion) of the total in unpaid refinancing loans were issued before Yanukovych came to power.

“You can find to whom you like to blame from this period,” she said.

That’s easy enough to do. At that time, Viktor Yushchenko was president, Yulia Tymoshenko was prime minister, Volodymyr Stelmakh was central bank governor and President Petro Poroshenko was a member of the central bank’s board of directors.

Through steady repayments, however, the total has been whittled down by Hr 29 billion ($1.1 billion – and now stands at Hr 81 billion ($3.2 billion).

“We estimate the recovery ratio will also be about 30 percent,” Gontareva said. Gontareva created a special division to recover non-performing loans due the central bank.

Source: National Bank of Ukraine, Deposit Guarantee Fund of Ukraine.

Firtash owes Hr 12 billion

Who are the leading deadbeats? More than 50 percent of the remaining amount owed is from five former bankers:

1 – Billionaire Dmytro Firtash, the fugitive oligarch who used to own the now-defunct Nadra Bank, owes Hr 12 billion (now $482 million). (Considering the loans were taken out in 2008-2009, they might have been worth $2 billion, since the hryvnia/dollar exchange rate was 5:1 throughout most of 2008.)

2 – Mykola Lagun, owner of the defunct Delta Bank, owes Hr 9 billion ($360 million).

3 – Oleh Bakhmatyuk, owner of the defunct VAB bank, owes Hr 10 billion ($400 million).

4 – Kostyantyn Zhevago, owner of the defunct Finance & Credit Bank, owes Hr 5 billion ($200 million); and

5 – Leonid Klimov, a member of parliament and owner of the defunct Imexbank, owes Hr 3 billion ($120 million).

Ukraine’s central bank has gone to court against Bakhmatyuk, Zhevago and Klimov, an independent lawmaker who used to belong to Yanukovych’s Party of Regions. All three men gave personal guarantees for the loans, Gontareva said, and the central bank won a court judgment against Bakhmatyuk. But he is appealing.

Forensic audits have recently been done on Nadra and Delta banks, but the findings are not public.

Revamping, regulating

Despite the shortcomings of the legal system – allowing remorseless impunity to continue – and a lagging recovery process, Gontareva is convinced that the future will be brighter with tougher regulation to prevent bank fraud and related-party lending.

This has been accomplished by changing the law in three ways:

1 – Requiring transparency in bank ownership and shareholders in banks;

2 – Rigorous monitoring of related parties of those owners and shareholders; and

3 – Legal responsibility of bank shareholders and managers for criminal wrongdoing.

“Two years ago absolutely nobody understood related parties and how to recognize them,” Gontareva lamented.

“We now know all the related parties for the biggest 20 banks, their lending portfolio, they’ve disclosed 100 percent of shareholders. It’s the main priority for this year – to set up proper monitoring, forward-looking risk-based supervision. We truly believe that will turn this banking sector around and even revamp the sector. We would like all these changes to be irreversible.”

Financial experts define risk-based supervision as an approach that devotes most of its time and resources on the biggest and riskiest institutions, rather than compliance-based supervision, described as an outdated approach where all the banks are treated equally and in line with pre-approved rules and procedures.

Only 20 banks will be left standing?

The Ukrainian banking sector of the future might have as few as 20 banks, which now constitute 88 percent of the industry’s assets. The next 20 banks account for only 8 more percentage points of the market. In other words, Gontareva said, the top 40 existing banks account for 96 percent of the market.

So, when the shakeout is complete, Ukraine could possibly go from 180 banks in 2014 to no more than 20 to 40 banks. This means at least another 60 banks could fail in the coming year.

Unless one of those banks is PrivatBank, which is by far the largest bank in Ukraine with more than 20 percent of all banking assets, the harm to Ukraine’s financial system is likely to be minor.

Privatbank’s special case

PrivatBank and its billionaire owner, Igor Kolomoisky, are touchy subjects for Gontareva. Simply bringing up his name constituted a “provocation” during the Kyiv Post interview. She did not speak of him by name and insisted that PrivatBank is treated no differently than any other bank in the nation, which seems to be at odds with the risk-based regulatory approach.

Many people are skeptical that PrivatBank is treated the same as any other bank. Its failure, some think, would destroy Ukraine’s banking system. Others note Kolomoisky’s political and business clout – including ownership stakes in Ukraine International Airlines and Ukrnafta, the state oil producer – as well as his willingness to wield power, backed by at least two dozen loyal members of parliament.

But Gontareva said Privatbank’s issues are manageable.

“It’s only how you organize a proper process of recapitalization and repayment of related party loans. If the shareholder is willing to do that, we will succeed with it,” Gontareva said. “We have a program. This program is signed and stamped. They will be in line with all other banking requirements. It’s not only a program for Privatbank.”

Under the terms of the International Monetary Fund’s four-year lending program to Ukraine, ending in 2018, functioning banks have four years to recapitalize and repay related-party loans, Gontareva said.

She doesn’t want to talk about specifics, however.

“I will not disclose any related-party loan portfolio of any banks in our countries,” Gontareva said, leaving it up to the public to simply have faith that the central bank is solving the problem.

Touchy subjects

Gontareva also tires of fielding questions about her work at Investment Capital Ukraine financial group, which she headed from 2007 to 2014, and her ties to Poroshenko, who chose ICU as his financial manager for arranging the sale of his confectionary corporation Roshen through a network of offshore companies after his 2014 election.

One allegation she debunked is whether ICU under her leadership improperly profited on the domestic bond market at the expense of the state taxpayers, as some documents circulating publicly purport to show.

“Everything that was written in this letter was false…It’s just an insinuation,” Gontareva said. “We didn’t even trade any securities with banks. We did only public auctions…ICU is the biggest trader of securities in this country. ICU was 10 years the biggest one and still the biggest one. I am happy for that. Because I started the organization with my partners. Before ICU, I was the biggest trader of treasury bills and bonds in 1996 in Societe Generale Ukraine. After I joined ING Bank, ING was the No. 1 securities trader. And ICU was the biggest trader – of course, ICU, 90 percent of their deals are linked to treasury bills and bonds. It is the biggest trader and broker and dealer of securities.”

Under her tenure, ICU had the “top position” and “everything was No. 1” – in treasury bills, managing assets and in research, she said.

ICU, Poroshenko’s offshore firms

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and Slidstvo, a Ukrainian investigative reporting group, on May 20 reported that nearly €4 million was moved out of Ukraine to a Poroshenko company in Cyprus.

The transaction, the Kyiv Post partner OCCRP reported, involved a combination of cash and in-kind payments. The cash payment would have violated the central bank’s currency control regulations in place at the time unless the Poroshenko company had a National Bank of Ukraine license for the transaction, which it did not.

“We didn’t issue any license because it was not any operation that needed a license,” Gontareva said. “We already publicly announced all of that. It’s not news.” Her explanation is consistent with the president’s disputed position that no currency was transferred abroad.

On another matter involving her time at ICU, OCCRP reported earlier this year that Yuri Soloviev, an official from the Russian-owned VTB bank, issued a 3 percent interest, $10 million offshore loan to her company six months before she took over as Ukraine’s top regulator. OCCRP also reported that the wife of the VTB official appears to have been Gontareva’s business partner. Specifically, OCCRP reported that in December 2013, an offshore company called Quillas Equities S.A., owned by VTB’s Soloviev, loaned $10 million to another offshore, Karanto Holdings Ltd., which is connected to Ukraine’s ICU – it had the same mailing address in Kyiv as ICU.

Gontareva said the loan had nothing to do with VTB and that commercial loans were a common practice in ICU’s business. “Traders never work using their own capital because their capital is limited,” she said.

Delta Bank scandal

There have been numerous reports of millions of dollars in money and assets being transferred out of several banks ahead of being declared insolvent by the central bank and on its way to liquidation by the state-financed Deposit Guarantee Fund.

Among the allegations is that her son, Anton, withdrew Hr 800,000 and her daughter-in-law even more money from Delta Bank after the central bank identified it as a problem institution. Gontareva responded bluntly: “Why should I discuss with you insinuation and bullshit?”

However, at worst, the transactions involving some failed banks suggest insider information allowed bank fraud and asset stripping. Consequently, the thefts increased financial losses for taxpayers who have to bail out depositors who lose their savings in failed banks, guaranteed by the state to a maximum of Hr 200,000 ($8,000) per individual.

At best, the transfers show that a dangerous delay and regulatory gaps exist in the process that prevents regulators from freezing transactions in a timely way.

“The NBU needs more legal tools to be able to deal with some of these issues more quickly,” said Qiamio Fan, the World Bank country director for Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova told the Kyiv Post. “From the time they identify a bank as problem to the point it’s declared insolvent, it takes too much time.”

Defends system in place

But Gontareva doesn’t see a problem, including with the failed Bank Mikhailovsky. “They decided to do a fraud and we caught them and sent them to liquidation,” Gontareva said. She said that Mikhailovsky’s owner and CEO, Viktor Polishchuk and Igor Doroshenko, respectively, fraudulently added Hr 1.1 billion ($44 million) to the balance sheet, evidently in an attempt to gain more state Deposit Guarantee Fund payouts for clients who lost their money.

The NBU “did not accept the balance sheet. We will not accept the balance sheet. We sent the claims to the police.”

Critics, however, note that the central bank put the bank under supervision in December, mysteriously lifted restrictions on transactions before the declared insolvency in March and that an attempt to change the bank ownership was registered in May, ostensibly to remove Polishchuk from criminal liability.

But the NBU press service said that “nothing cancels Polishchuk’s responsibility for Mikhailovsky.”

Depositors, meanwhile, say they were duped by the bank into transferring their money into a related investment company and deserve to have their losses covered by the state fund.

Gontareva and Deposit Guarantee Fund head disagree.

“I even publicly announced the sentence should be five years (in prison) for each of them,” Gontareva said of Polishchuk and Doroshenko. “What else should I do? Maybe I should kill them or what?”

Whatever happened, considering that 2,000 cases of suspected bank fraud have been referred to police and prosecutors with no result since 2014, there is no reason now to think that the criminal justice system will start working on the Bank Mikhailovsky case.

Source: Deposit Guarantee Fund of Ukraine, National Bank of Ukraine.

Central bank credibility

When asked whether the failure to prosecute any bank fraud undermines the central bank’s regulatory powers, Gontareva said the credibility of the institution she leads will be judged in other ways.

“Our credibility is more on the territory of fighting with inflation, a new monetary policy…a clean-up of the banking sector,” she said. “We are ahead of a lot of our peers in the world right now. We are like a role model for other central bankers on how to clean up the banking sector.”

She doesn’t expect that future losses will be high because, after asset-quality evaluations and stress tests, “we know what’s going on in the top 20 banks that are 88 percent of the banking system. I am really proud we know what’s going on.”

Many of the groundless attacks against her and the central bank, she said, come from oligarch-owned media.

“Because of all this tough fight with oligarchs and all the mass media in their hands, you cannot expect anything good on TV and the press,” Gontareva said. “But in the international community and among bankers here, we have very high credibility.”

IMF lending

Gontareva said the prospect of reduced IMF lending or a slower payout in 2016 should not affect the central bank’s goals, including lowering of interest rates and relaxation of hard currency restrictions designed to help protect the value of the hryvnia – the national currency that has lost two-thirds of its value since 2014.

“It’s not a big deal for us,” she said of reports that the IMF in July will approve only a $1 billion loan installment instead of the planned $1.7 billon. The IMF’s thinking appears to be to delay until greater progress is made by Ukraine in the anti-corruption drive.

Russian banks

She also sees no reason why, despite Russia’s war against Ukraine now in its third year, Ukraine should exclude Russian-owned banks, with 15 percent of the banking market, from doing business in Ukraine.

The top three Russian-owned banks are Sberbank, VTB and Prominvest.

One argument undermining Ukraine’s call for tougher sanctions on Russia from Western governments is the continuing business done between Ukraine and Russia. Critics note that Ukraine was slow to formally adopt trade and other sanctions against Russia, and that it took a blockade by activists last year to stop commerce between the Ukrainian mainland and Russian-occupied Crimea. Moreover, Poroshenko keeps doing business in Russia with his Roshen confectionary subsidiary.

Gontareva doesn’t see the problem.

“VTB is facing very specific sanctions. It doesn’t prohibit them from operating locally. They have their correspondent accounts in the USA and Europe. The prohibitions prevent them from borrowing on the international markets more than 90 days,” Gontareva said. “To prevent financial instability, we treat them equally with all other banks. Of course, we are regulators, not political animals here. If our security council decides these banks should not be on our territory, we will react accordingly.”