Take any large Ukrainian company and they will likely promote themselves as being vertically integrated. Enthusiasts of the management solution argue that bringing the whole production life cycle in a given market under a single holding increases efficiency and sorts out a firm’s finances. But this trend – one of the main drivers of mergers and acquisitions – also belies a lack of trust among market participants, and can encourage the transfer of profits offshore.

The management strategy of vertical integration involves bringing together companies working on different stages of a single product under one holding structure. For a poultry producer, for example, this can involve buying up land to produce feed, employing its own fleet of transport trucks, and having its own brands or even retail outlets to sell directly to consumers.

Internationally, the trend took off during the industrial era, with rail, steel and other giant firms dominating the market. The arguments in favor of it were fairly straightforward: lower transaction costs, synchronize supply and demand and the possibility to monopolize an entire market.

It also helps boost independence and protection from rivals, no doubt one of the reasons why Ukrainian companies are so quick to seek this option. You don’t need to worry about good relations with power companies, the argument goes, if you produce energy in-house.

Indeed, agricultural companies like poultry producer MHP and sugar giant Astarta lead the nation in turning biowaste into fuel.

But the strategy also involves a lot of risks. Costs of coordination can eat away profitability, it’s very difficult to switch suppliers, and the motivation of specific sections falls fast once you remove the need for market rigour. An article on company strategy in McKinsey Quarterly, the business consultancy’s publication, boils down the problem of such a strategy – it’s complex, expensive and hard to reverse.

“Don’t vertically integrate unless it is absolutely necessary to create or protect value,” the article warns.

But this has not deterred Ukraine’s biggest industrial players, who continue to pursue the strategy with an insatiable appetite. Energy giant DTEK has used upstream and downstream acquisitions to become one of the nation’s three biggest companies. It now combines coal mines, coal enrichment plants and thermal power stations, and it is actively buying up power distributors.

„Vertical integration is one of DTEK’s competitive advantages. It helps the company to benefit from synergies of its coal-producing and power-generating companies, to be more flexible and effective,” Maria Pomazan, a company spokeperson, told the Kyiv Post. „Looking to the future, we also think

of the prospect to conclude direct contracts between our power generation and sales when the electricity market is liberalized.”

„DTEK has weathered the global economic crisis, which proves the company’s business model: the vertical integration of operating companies provides necessary insurance and the possibility for further development even in an unfavorable environment,” Pomazan argued.

But even if it’s good for an individual company, it doesn’t always benefit consumers. This is particularly true in Ukraine, whose economy remains heavily influenced by monopolistic Soviet-era structures, warned Iryna Akimova, currently first deputy head of the presidential administration, in a 2001 policy paper. Since then little has changed, with the economy being dominated by large industrial groups.

Yet according to Alexander Boboshko, a senior associate at law firm Schoenherr’s Kyiv office, much of the apparent vertical integration is actually clarifying on paper what already exists in practice. Ukraine’s large groups typically operate on the basis of a gentlemen’s agreement’s, he said, which are formalized when companies need to tap Western capital markets.

„The issue driving vertical integration in Ukraine is first, the need to do international financial reporting … so that you can prove that you are actually in control of this or that business,” he said. „Moreover, international investors don’t invest in structures they don’t understand … If you take a mid-level business in Ukraine and you try to draw its corporate structure you will find that it is made up of 50 entities owned by people with no relation to each other.”

But there is one more reason for its use, namely taxes, Boboshko adds. By ensuring that holding strucutures are located in tax havens, it is possible to minimize the taxes on dividends to guarantee favorable conditions for an intra-company loan, or repatriate profits in an efficient manner.

„Tax minimization is one of the main reasons for vertical integration, not just in Ukraine but around the world,” Boboshko said.

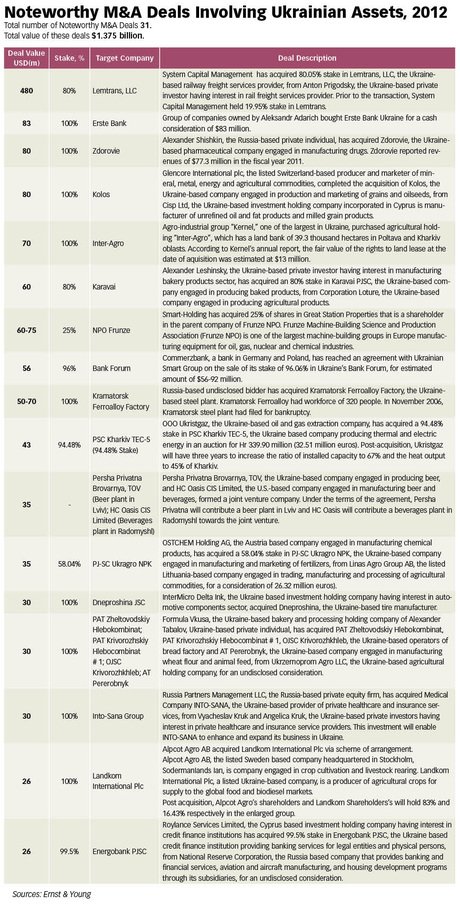

Noteworthy M&A Deals Involving Ukrainian Assets, 2012

Total number of Noteworthy M&A Deals 31.

Total value of these deals $1.375 billion.

Kyiv Post editor Jakub Parusinski can be reached at [email protected]