Analysts say that the upswing in birthrates is not enough to stop the longstanding slide in Ukraine’s population.

After many years of decline, Ukraine’s birthrate has begun to inch up, growing by about 8 percent year-on-year in 2006, according to a study released by the Institute of Demography and Sociological Research (IDSR) at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences.

But analysts say that the upswing in birthrates is not enough to stop the longstanding slide in Ukraine’s population.

The study, released in late March, shows that birthrates have been steadily rising in the past several years after more than a decade of decline sparked by the economic collapse that followed the breakup of the Soviet Union.

More than seven years of successive and sharp economic growth has raised living standards for many Ukrainians, increasing their ability to build families and spend new income on newborns.

But the overall population of the country continues to shrink.

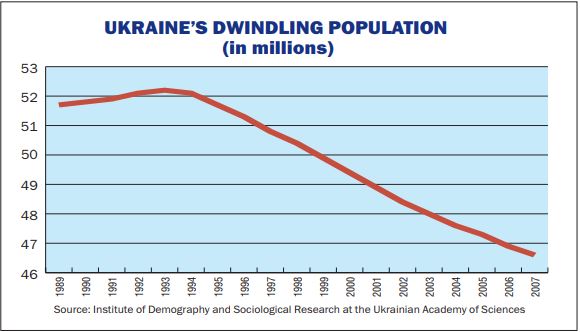

Since 1993, the population of Ukraine has fallen from 52.2 million to about 46.7 million, largely as a result of a growing death rate and lower life expectancy.

Although the government has introduced incentives intended to increase new births, analysts say that birthrates are not expected to grow much higher due to tight economic conditions for most Ukrainians combined with a general European trend favoring single-child families and women putting career ambitions ahead of having children.

Grim forecasts

According to the State Statistics Committee, Ukraine’s population is shrinking by some 300,000 people annually. Just over 700,000 citizens died last year, while others emigrated out of the country.

The IDSR forecasts that Ukraine’s population will fall to approximately 36 million people by 2050, with the elderly comprising 32.5 percent of this total.

IDSR director Ella Libanova said the average life expectancy in Ukraine is about 10 years below that of European countries. On average, men in Ukraine live to 62 years of age, while 73 is the average lifespan for women.

Thanks to improved medical care and rising living standards, the lifetime expectancy rate in Ukraine is expected to eventually rise to 79.5 years for women and 71.5 years for men.

But the downturn is expected to continue nevertheless. In addition to Ukraine’s aging population (currently, about 20.4 percent is over the age of 60), the country also suffers from a high death rate among its able-bodied population.

Ukraine`s population graph by the Institute of Demography and Sociological Research (IDSR) (scan)

Andriy Bychenko, director of sociological services at the Razumkov Center for Economic and Political Research, a Kyiv-based think tank, said the country’s able-bodied male population is dying early due to alcohol abuse and smoking, both of which cause heart disease and cancer-related deaths. These problems are common among lower income segments of the population, he added.

Rising birthrates have compensated a bit.

Ukraine has seen its birthrate rise from nine births per 1,000 people in 2004 and 2005 to a rate of 9.8 in 2006.

The institute expects that birthrates will peak this year and that deaths will fall somewhat, particularly among children and able-bodied males due to improved medical services. However, the country will also see a rise in its aging population.

ISDR analysts say that short-term incentives are not enough to fundamentally change the current situation. A complex program aimed at raising incomes, improving healthcare and reversing massive emigration are required.

Birthrate up, but not enough

Libanova said one contributing factor to the higher birthrate is a government incentive introduced in 2005 that provides families with Hr 8,500 ($1,700) for every newborn.

“Based on the experience of other countries, similar reforms can only lead to short-lived results for some two or three years. But for noticeable and stable results a more complex approach is required. In particular, the cost of raising a child needs to be lowered,” she said.

Analysts at the Razumkov Center do not attribute the increased birthrate solely to the government incentive, explaining that a large percentage of women born in the 1980s are now reaching childbearing age and that many middle-aged women who put births off during the 1990s are now more inclined to become mothers.

A contributing factor to the rising birthrate is the considerable reduction of abortions achieved by national programs on family planning and reproductive health, improvements in reproductive healthcare and safe-sex education among youth.

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the abortion rate in Ukraine fell from 126 abortions per 1,000 live births in 1999 to 50 in 2006 and continues to decrease.

UNFPA Program Officer Oleh Voronenko said two-thirds of Ukrainian families currently have only one child.

Voronenko said that a moderate depopulation due to natural decline is occurring throughout Europe and other developed countries.

However, unlike developed countries that benefit from higher living standards, lower death and higher life-expectancy rates, Ukraine’s depopulation is occurring at a much more rapid pace, intensified by the country’s health problems and lower living standards.

“In most of the developing countries in Asia and Africa we see positive population growth despite very high mortality due to a very high birthrate, which is connected to local family and societal traditions,” Voronenko said.

The trends observed in Ukraine are common to other post-Soviet countries, according to Voronenko.

“Ukraine’s main problem is not the birthrate, which is more or less on par with other European countries, but a high death rate, which has grown considerably over the last 15 years and exceeds the birthrate by almost two times,” Voronenko added.

According to IDSR, 16 out of every 1,000 Ukrainians die each year. In comparison, less than 10 out of 1,000 Europeans die each year.

In Ukraine, the birthrate is 1.2 children per childbearing woman, while in Europe, that figure is 1.4.