Archbishop Yevstratiy Zoria’s long red hair is tied back, and a gold chain is draped over his black robe. At the end of the chain hangs an oval, jeweled medallion with an icon bearing an image of the Virgin Mary and the baby Jesus in the center. Zoria says his medallion, called a Panagia, was a gift from Metropolitan Volodymyr, the late former head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate.

But for Zoria to be wearing this Panagia seems almost inappropriate. The archbishop belongs to the Kyiv Patriarchate, an Orthodox Church that rivals the Moscow Patriarchate in Ukraine. The two patriarchates, both claiming to represent the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, have been in conflict since the Kyiv Patriarchate split off from the Moscow one in 1992. Zoria said that when the Metropolitan gave him the gift in 2005, the relationship between the two churches was not so hostile. But at this point, the medallion looks like a gift from behind enemy lines.

If the Kyiv Patriarchate is the Russian church’s prodigal son, claiming independence, then the Moscow Patriarchate in Ukraine is its obedient one. The Kyiv Patriarchate is considered a schismatic church, illegitimate in the eyes of the international Orthodox community. But in June, the Ukrainian parliament urged Bartholomew I, the head of the Pan-Orthodox Council, to consider creating a unified Ukrainian national church and grant canonical legitimacy to the Kyiv Patriarchate.

Hybrid holy war

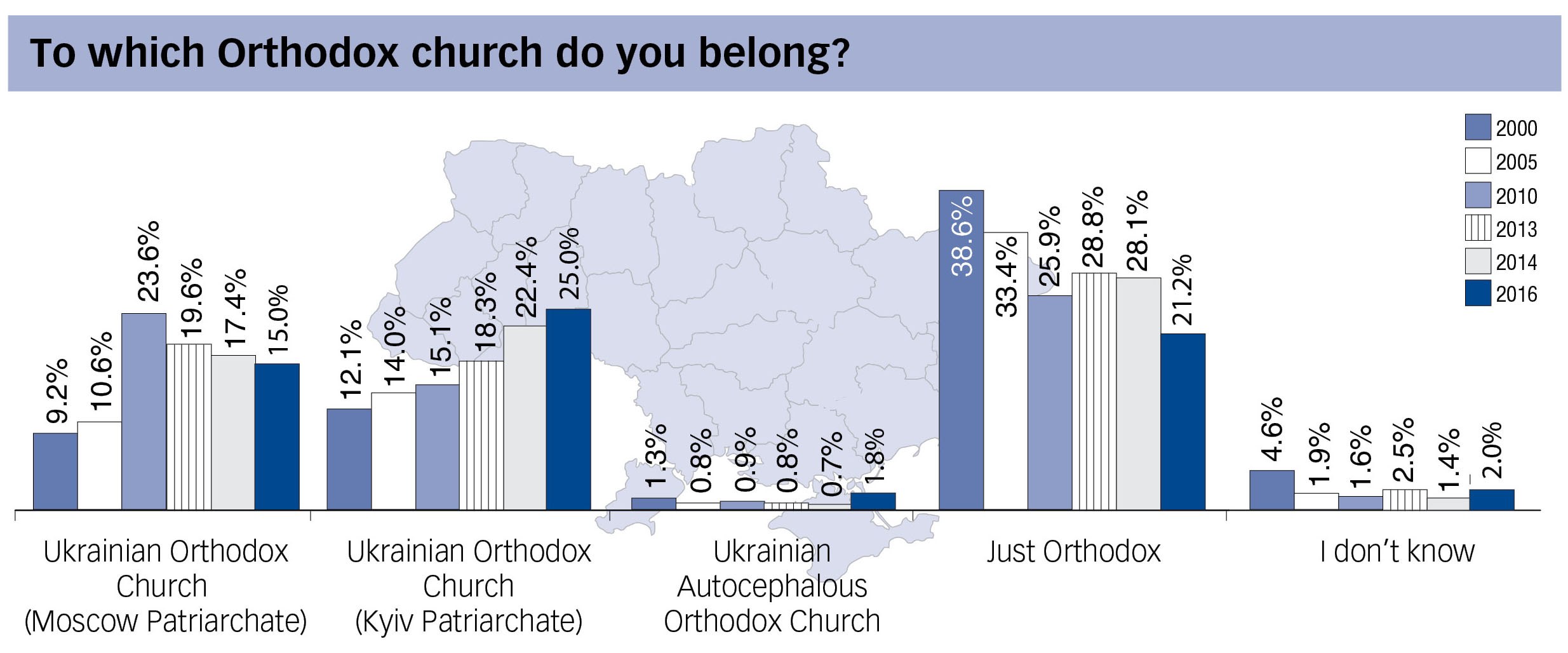

About 65 percent of Ukrainians are members of eastern Orthodox churches, totaling about 27.8 million people. The popularity of the Moscow Patriarchate has been waning in recent years, while support for the Kyiv Patriarchate is only growing. Allegiance to the Kyiv Patriarchate has grown steadily, from 12 percent in 2000 to 25 percent in 2016, while allegiance to the Moscow Patriarchate fell to 15 percent of the country this year, according to a survey by the Razumkov Center.

But rising support for the Kyiv Patriarchate has come at a price—heightened polarization. The percentage of people who are Orthodox but do not associate with either patriarchate fell from 39 percent in 2000 to 21 percent in 2016, a survey by the Razumkov Center survey said. The Ukrainian people have increasingly been forced to choose sides—first in politics, and now in their religion.

Where support for the Kyiv Patriarchate is especially high, the people are also particularly polarized. In the west, where nationalism is also at an all time high, 36 percent belong to the Kyiv Patriarchate and 10 percent to the Moscow Patriarchate. Only five percent say they are “just Orthodox” without taking sides, compared to 21 percent throughout the country.

People are leaving the Moscow Patriarchate for the Kyiv Patriarchate amid Russia’s war against Ukraine, according to a nationwide survey of 2,018 conducted by the Razumkov Center in March 2016.

At a time when the Ukrainian people are becoming increasingly politicized and estranged from one another, the Orthodox church might have united them. Nearly 60 percent of Ukrainians trust the church, compared to 17 percent who trust the president and a dismal 6 percent who trust the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s parliament, according to a 2015 survey. But the church itself is sharply divided along political lines, and the divide has only heightened since Russia started its war against Ukraine in the east.

“Moscow is using its influence over Ukraine in the church as an instrument of hybrid warfare against Ukraine,” Zoria said, painting the Moscow Patriarchate in Kyiv as a pro-Russian weapon.

Tensions between the two churches got so bad in 2015 that in one incident, a priest from the Moscow Patriarchate church stabbed a priest from the Kyiv Patriarchate, allegedly shouting “For Rus! For the Orthodox faith!”

Establishing a national Ukrainian Orthodox Church is just one way Ukraine is trying to rid itself of Russia’s influence. Verkhovna Rada speaker Andriy Parubiy, who pushed for the request to Bartholomew I to pass, argued that the creation of a national church independent from Russia’s influence is a matter of national security.

“There is economic aggression, which we have seen for many years, but there is also political meddling in the spiritual life of Ukraine,” Parubiy said in a parliament press release. “Ukraine as a nation must do everything possible to not allow outside powers to provoke division among the Ukrainian people for any reason, especially religious.”

Political persecution

However, the Moscow Patriarchate in Ukraine sees parliament’s request for autocephaly, a term signaling autonomy in Eastern Orthodoxy, as the latest in a long series of aggressive measures aimed at dismantling its church.

The head of the church’s information department, Bishop Kliment of Irpin, goes as far as to say his church is under attack.

It is by the grace of God that the Moscow Patriarchate has survived amidst political persecution, Kilment said. He went on to accuse the Kyiv Patriarchate of seizing its churches throughout Ukraine. In June, the Moscow Patriarchate website published photos of militants from the Right Sector ultranationalist organization in army uniform taking control of a church in a village in Ternopil, one of many such posts by the site.

Though the Ukrainian question will not be considered at the historic Pan-Orthodox Council, Kliment still described the move by legislators as violation of the separation of church and state and an infringement on religious freedom in the country.

“If the canon changed every time the politics changed, the church would change its laws every two to three years,” he said, speaking in his office on the territory of the famous Kyiv Pechersk Lavra Monastery after returning from evening services on the Day of the Holy Spirit.

The Moscow Patriarchate denies all claims of Russian influence. “We are not administratively or economically dependent on Moscow,” Kliment said. In 1990, the Moscow Patriarchate granted its church in Ukraine maximum autonomy, giving it the power to appoint its own bishops and manage its own financial and economic affairs.

Kliment also denied allegations of its pro-Russian stance. “We are accused of supporting separatists. In official documents, we always say that Crimea is Ukraine, that the war in the Donbas must stop immediately.”

But a press release by the Moscow Patriarchate on the eve of the Russian invasion in Crimea in 2014 casts doubt on the church’s pro-Ukrainian stance. “Let us hope that the mission of the Russian warriors defending freedom and the identity of those people and their very life will not meet staunch resistance leading to large-scale clashes,” the press release read.

Spiritual aid

For Father Sergii Dmytriev, head of the Kyiv Patriarchate’s social policy department, the fact that the Ukrainian Church does not have its own Patriarch is enough to prove its lack of autonomy.

The Kyiv Patriarchate, on the other hand, has made itself out to be the people’s church, supporting first the protesters during the Euromaidan Revolution, and now the Ukrainian soldiers fighting against Russian-backed separatists.

“The Kyiv Patriarchate is the spiritual aid of any person fighting for the interests of the country,” Dmytriev said over lunch, wearing a blue t-shirt he would later cover with a black church robe. Dmytiev had just come from the hospital, where he was visiting a Ukrainian soldier.

During the revolution, the patriarchate opened the doors of its golden-domed Mikhailovsky Monastery to protesters as a safe haven and later, as a hospital. In a dramatic moment, when Berkut police began attacking protesters on the eleventh night of the revolution, Mikhailovsky rang its alarm bells for the first time in 800 years in support of the protesters. The bells continued to ring for eight hours, until the police retreated.

Zoria sees parliament’s request as an attempt to right a long-standing, historical wrong against the Kyiv Patriarchate. He invoked the political rhetoric of annexation to describe the unjust plight of his church.

“Moscow annexed Kyiv’s Metropolitan in 1686 by threatening military pressure,” Zoria said. “This was a violation of the canon in the first place.” At the request of the Russian tsar, the Kyiv Patriarchate was transferred from the jurisdiction of the Constantinople Patriarch to Moscow’s in the late 17th century.

Moscow lays historical claim to the Orthodox church in Ukraine, just as it does over annexed Crimea, which Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev gave to Ukraine in 1954.

In most independent nations, the Orthodox churches have been granted autocephaly. The Patriarch of Constantinople finally recognized the autocephaly of the Georgian Orthodox Church in 1990, after a long fight to gain independence from the Russian Orthodox Church. Even in countries like Poland, where Orthodox Christians are a minority, the church is autonomous. But Ukraine’s legitimate orthodox church has remained under Moscow’s jurisdiction.

Religious battlegrounds

Archbishop Zoria works at the Monastery of St. Theodosius, a modest church with green domes. Directly across the street is the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra Monastery, the heart of the Moscow Patriarchate in Ukraine. In a city peppered with cathedrals, the two patriarchates often find themselves squeezed into close quarters.

Opposite the golden-domed Mikhailovsky Monastery, the Kyiv Patriarchate’s most famous church, stands St. Sophia, historically a Moscow patriarchate church. Today, St. Sophia no longer holds active services, but, in an unexpected twist, a smaller church on its grounds hosts priests from the Kyiv Patriarchate every evening.

Outside Kyiv, even this uneasy coexistence has proved impossible. What the Moscow Patriarchate describes as church seizures, the Kyiv Patriarchate sees as the will of growing numbers of Kyiv Patriarchate believers. The real travesty is that the Kyiv Patriarchate has more constituents and fewer churches than the Moscow Patriarchate, Dmytriev said.

“What is really happening is that people from the Moscow Patriarchate want to transition to ours,” Dmytriev said. Mikhail Mishchenko, the deputy director of sociological research at the Razumkov Center, confirmed Dmytriev’s claim. Mischenko explained that the “seizures” happen in villages where there is only one church, and the villagers are divided over patriarchal allegiance. If most of the villagers want to change to the Kyiv Patriarchate, but a minority want to stay in the Moscow Patriarchate, an aggressive conflict might ensue, Mischenko said.

Kliment accused the Kyiv Patriarchate of an “intimate symbiotic relationship” with the radical political party, Praviy Sector, the group allegedly helping seize churches. Zoria said he supported them only to same extent that he would support any political parties fighting for Ukraine’s autonomy. Dmytriev hinted at a closer relationship, but emphasized that the group’s influence was overblown in the media.

The Kyiv Patriarchate mostly holds their services in modern Ukrainian, while the Moscow Patriarchate—in Church Slavonic or modern Russian. When asked if the divide between the patriarchates was language-based, Dmytriev and Zoria explained that language was not the deciding factor. Like the political divide, language is only element of Ukrainian nationalism, but Russian speakers are not necessarily shamed.

Dmytriev, a Russian-speaker himself, said that he was not forced to speak Ukrainian after the war, but he felt it was important to. Speaking Ukrainian is “a kind of protest, a way to defend ourselves” against the onslaught of russification,” Dmytriev said. But Zoria said it was most important for churchgoers to understand what is preached; some Kyiv Patriarchate churches hold services in Russian if that is the language their congregation speaks.

“It’s not about difference in faith. We are of one faith,” Zoria said of the two patriarchates. The difference is purely political. Zoria went on to say that the Kyiv Patriarchate welcomes all political parties – except ones that are against Ukraine as an independent state.

“A person should not see the church as a continuation of politics. It is only anti-Ukrainian parties that we do not associate with. We welcome all the other parties, and keep up relationships with all of them,” Zoria said.

Zoria’s exception speaks to the partisan rhetoric used by church leaders of both patriarchates, each accusing the other of aggression.

Both churches are well-versed in the language of victimhood and finger-pointing. “Unlike the church of the Moscow Patriarchate, which is used to leaning on the regime for its power, the Kyiv Patriarchate has always relied on the Ukrainian people,” Archbishop Zoria said. “We have never had support from the government. We have survived only by the support of the people.”

In an interview just two days before, Bishop Kliment accused the Kyiv Patriarchate of relying solely on the support of the government to stay afloat.

The numbers show increasing support for Ukrainian autocephaly — 48 percent in 2016 compared to 38 percent in 2013, with only 10 percent of Ukrainians preferring to remain subordinate to Moscow. These numbers are an expression of burgeoning national spirit in Ukraine, but they also tell of an increasingly alienated, pro-Russian minority. And Ukraine’s churches are not helping bridge the divide, but rather are widening it

A version of this article appeared in print on June 24, 2016.