Ukraine’s middle class currently accounts for only a small part of Ukraine’s society and is a far cry from being a girder of the nation’s economy

While a middle class has visibly emerged in Ukraine in the last several years, it currently accounts for only a small part of Ukrainian society, and is still a far cry from being a girder of the nation’s economy, as in other more developed countries.

A recent study shows that while the middle class in Ukraine currently accounts for less than one-tenth of the country’s population of around 47 million, more than a third of Ukrainians subjectively feel themselves to belong to the middle class.

The Kyiv-based market, consumer and sociological research and consulting organization Gorshenin Institute of Management Issues (KIMIG), which conducted the survey among 2,000 respondents in the second half of April, found that 8.9 percent of Ukrainians actually belong to the middle class.

By contrast, the middle class in most European countries on average accounts for 50-70 percent of the population.

Of the respondents polled by KIMIG, 33.6 percent, or more than one-third said they saw themselves as middle class.

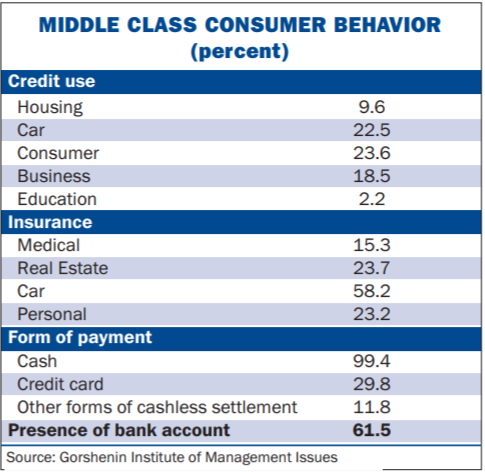

The poll’s margin of error was 2.2 percent. The criteria used in the survey to determine respondents’ socio-economic status included personal income, educational level and aspects of their consumer behavior.

According to the director of the Razumkov Center for Economic and Political Studies’ sociological department, Andriy Bychenko, the percentage of those who consider themselves middle class depends on the criteria used to describe that class.

“In the Western understanding, Ukraine does not have middle class at all, since all of the conditions [for the existence of that class] have not been met. This is due primarily to financial factors. A middle class has a genuinely middle level of income, which is supposed to allow them certain privileges,” Bychenko said.

“In Ukraine, income that can be considered mid-level is still unable to afford European standards of living and the consumer behavior that corresponds to that.”

The Razumkov Center conducted its own research on Ukraine’s middle class in 2004 and reports that since then, the number of Ukrainians who consider themselves middle class has grown from 40 percent of the population in 2004 to 54 percent today.

According to the KIMIG poll, 8.7 percent of respondents estimated their incomes at between $400-1,000 a month, 2 percent at $1,000-2,000, and 0.7 percent at more than $2,000 a month.

Nearly 21 percent of respondents said they earned incomes of $200-400 a month, 34 percent (the highest percentage of those polled) said they made $100-200 a month, and nearly 31 percent (the second highest percentage) said they earned less than $100 a month.

State figures show that the official monthly salary in Ukraine grew by around 28 percent in 2006 year-on-year, with the average salary standing at just over $200 one year ago last summer.

In the first quarter of this year, salaries in the financial sector were among the highest, averaging more than $500 a month. The lowest salaries were found in the agriculture and health services sectors, with an average of around $120-160 a month.

The capital Kyiv boasted the best-paid labor force in the country in the first quarter, with average salaries of nearly $400 a month. Following Kyiv were the highly industrialized Donetsk and Dnipropetrovsk regions, where average monthly salaries stood at about $220-250 per month. The lowest average monthly salary, a little more than $150, was in western Ukraine’s Ternopil Region, where high-paying jobs are scarce.

Independent dependents

Bychenko said that due to its small size, Ukraine’s middle class does not perform the role of economic stabilizer as the middle class does in more mature economies. He said that a real middle class was very important for a country’s economy, since it influences that economy and its growth directly through tax payments and commercial consumption.

He added that in the West, these two factors were economically determinative, meaning that while the middle class is independent, the state depends on the middle class.

“In Ukraine, we can observe the opposite situation: The state is economically independent from the middle class, which, due to its small size and low consumer activity, does not have any influence on the country’s economy,” Bychenko said.

He added that when the middle class comprises the majority within a society, many members of that class possess high professional qualifications, making their country more economically competitive in the world.

KIMIG head Kost Bondarenko said the main reason behind the large disparity between Ukraine’s middle class and the rest of the population is the poor financial standing of most of the country’s intellectuals, who share characteristics of the middle class but cannot be considered among its number.

“The point is that in Europe, most professions traditionally associated with intellectuals, such as physicians, teachers and engineers, are very well paid and thus form the middle class,” Bondarenko explained.

“In Ukraine, these occupations are still mostly state-funded, which is a synonym for being poor. Consequently these people are budget-dependent, with their salaries often being below subsistence levels,” he added.

“In fact, in Ukraine, about 14 million people are paid by the state and about 17 million are pensioners, which altogether accounts for more than half of Ukraine’s population.”

New class, new behavior

As in more developed market-economy countries, the rise of Ukraine’s middle class is reflected in increasing consumer spending and consumption, savings, and bank loans for household items, automobiles, apartments and private homes, and business development.

Bondarenko said, however, that as consumers, Ukraine’s middle class is still obliged to spend the lion’s share of their incomes on food and other living essentials. Most Ukrainians currently spend up to 90 percent of their incomes on food. According to Bondarenko, a Ukrainian making $1,000 a month typically spends around half of that amount on rent and the rest on food.

He said that in contrast to a genuine middle class, Ukraine’s middle class is still limited in its purchasing power and cannot spend as much money as middle classes elsewhere do on high-quality goods, vacations, and insurance.

“As a result, it turns out that although they are middle class in their ideology, these people [the Ukrainian middle class] still cannot be considered fully middle class.”

Because the middle class in Ukraine is still in its early stages of development, it hasn’t developed sociological patterns of behavior that would anchor it to a set of traditional values, among them, political values and voting patterns, such as those developed among the middle classes of other European countries.

According to KIMIG’s research, that’s why it is still too early to refer to Ukraine’s middle class as a separate social category. Ukraine’s middle class is less politically active than its European counterparts, although it tends to express greater interest in political issues than other stratums of Ukrainian society.

According to Bondarenko, Ukraine’s middle class predominantly supports the pro-Russian Party of Regions, with about 38 percent of the country’s middle class favoring that party. More than 20 percent give their support to Byut, led by fiery oppositionist Yulia Tymoshenko, while nearly 7 percent support the pro-presidential Our Ukraine.

A June 2007 poll of political preferences conducted nationwide by the Razumkov Center showed nearly similar results, indicating that of those Ukrainians planning to vote in the upcoming early parliamentary elections Sept. 30, a little more than 37 percent plan to vote for the Party of Regions, more than 21 percent plan to vote for Byut, and 8.5 percent will cast their votes for Our Ukraine.

According to Bychenko, these combined results indicate that the political preferences of Ukraine’s middle class do not differ from those of Ukraine’s population on the whole.

Some foreign observers say Ukraine’s middle class has definitely started to take shape and forecast good prospects for its further development.

“I can say for sure that Ukraine has a middle class now,” said Slovenian ambassador to Ukraine Primoz Seligo.

“I arrived here three years ago and have witnessed lots of changes in this respect. I am convinced that the only thing needed for [the middle class] to become well-structured and numerous is time and it will definitely meet European standards,” said Seligo.

According to Seligo, Slovenia’s middle class is about 80 percent of that country’s population, one of the highest indicators for the middle class in Europe.

“The middle class in Ukraine is coming to realize that it should not wait for somebody to do something for them, but they increasingly understand that they should take action themselves,” said the Netherlands ambassador Ron Keller, who has also spent the last three years in Ukraine.

“This can only be done effectively if people organize themselves into NGOs or political parties,” Keller said, adding that it would take time for Ukraine’s middle class to organize itself to influence decision-making “from the bottom up.”

Keller said that the middle class in the Netherlands is around 60-80 percent of the population and accounts for the bulk of employment and wealth creation in that nation.

“They [the Netherlands middle class] are heavily organized and active in many NGOs, from labor unions, branch organizations, to environmental lobby groups, and so on. And all of these organizations influence political parties, parliament and the government in one way or another,” Keller said.

He added that his country’s middle class was also the engine that drove small and medium-sized businesses, which “are the essential factor in innovations in our economy. They are the most flexible and modern part of our economy.”

Bondarenko said that the further development of the middle class in Ukraine depends mostly on the political situation in the country and the existence of a plan for the development of the nation’s economy.

“While the development of the middle class depends on a market economy, the health of the middle class is in turn an indicator of a mature market society,” he said.