On the frosty morning of Feb. 25 three years ago, Viktor Yanukovych was sworn in as the fourth president of Ukraine. He had won the votes of almost 12.5 million people, or 48.95 percent, beating Yulia Tymoshenko, who got close to 11.6 million votes, or 45.47 percent.

Both supporters and opponents of Yanukovych thought that, like it or not, the trajectory of his presidency would be clear. Yet the intervening years saw its share of surprises. Here are some of them:

Myth of pro-Russian president

Yanukovych was labeled pro-Russian during the 2004 Orange Revolution, when he lost the decisive round of presidential election to rival Viktor Yushchenko. In his unsuccessful quest, Yanukovych enjoyed strong support from outgoing President Leonid Kuchma and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

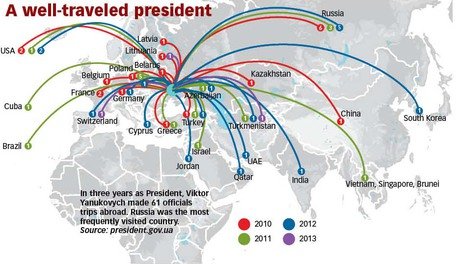

Upon election to the presidency in 2010, he made six official trips to Russia, more than any other country. In April 2010, Yanukovych signed the controversial Kharkiv Accords, allowing the Russian naval fleet to remain stationed in Crimea until 2042 for a $100 discount per 1,000 cubic meters on natural gas imports from the price negotiated a year earlier by ex-Prime Minister Tymoshenko. But relations between the two countries have since soured. Ukraine pays one of the highest gas prices in Europe, and Moscow is pushing Ukraine to join the Russian-led Customs Union in exchange for further gas discounts.

“Russians definitely did not expect his obstinacy. Putin thought he can outsmart Yanukovych, pressure him into entering the Customs Union. But he is holding on and turned out more difficult for Russians to deal with than Yushchenko was and Tymoshenko would have been,” says political analyst Vadym Karasiov.

Myth of oligarch puppet

Yanukovych was largely per – especially billionaire Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine’s richest man and financial backer of the Party of Regions. Instead, Yanukovych has taken care to boost the fortunes of “The Family,” a loyal group of advisers who occupy top spots in the government. In particular, the president’s son, Oleksandr, has been a top recipient of government tenders and his company MAKO was recently estimated by PwC to have a net worth of Hr 1.7 billion.

“Nobody expected him to be monopolizing power both in the country and in business. President Kuchma was balancing among clans. He was the moderator. He never created his own clan number one, like Yanukovych has. Therefore, Yanukovych, in fact, received much more real power than even Kuchma, who was considered authoritarian,” Oleksiy Haran, director of the school for political analysis at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy, said.

See the list of Yanukovych’s bloopers gathered up by Kyiv Post.

Myth of pragmatic team

The business community, optimistic in 2010, is now largely disappointed. Many thought the wealthy businesspeople in the Party of Regions would bring pragmatism, professionalism and stability.

Indeed, the state’s administrative capacity has improved. Experts praise the adoption of new, progressive legislation, particularly the Tax Code and Criminal Code. Natalie Jaresko, CEO of private equity firm Horizon Capital, runs down a list of successes: regulatory improvements helping reduce bureaucracy; a successful Euro 2012 football championship; the signing of the Shell natural gas development agreement; and steps toward pension reform.

Yet this has not been enough to make up for rising corruption and corporate raidership, which have all but blocked off further investment.

“Ukraine failed to recoup the GDP (gross domestic product) it lost in 2008-9, conduct structural reforms, improve its business climate, deal with corruption, foster fair competition, and eliminate red tape,” says Alexei Kredisov, managing partner at Ernst & Young Ukraine.

“As a result, a small handful of businesses report good results and are expanding their operations. The majority of other businesses show poor results, have negative expectations for the future, and are scaling down their investments and employment – as reported by the latest business leaders’ poll conducted by the European Business Association, which unites over 900 companies.”

Myth of strong opposition

Many political analysts and opposition members confess that Yanukovych’s quick seizure of power in the executive, legislative and judicial branches came as a surprise. “After just a month in power, Yanukovych canceled the political reform of 2004, going back to the Constitution of 1996 with more power for the president. It became clear that the Constitutional Court, as all (other) courts, are in Yanukovych’s pocket,” says Volodymyr Fesenko, head of Penta think tank. “After this, many were surprised how easily some members of parliament from the opposition joined the pro-presidential faction in parliament. So, Yanukovych had all the power in his hands – the government, the parliament, and the courts,” says political analyst Vadym Karasiov.

“Most people underestimated Yanukovych. We thought he was more simple minded, primitive, if you will. But he turned out to be a very effective Machiavellian autocrat,” Karasiov adds.

Myth of tolerating opposition

Few, if any, expected Yanukovych would let Tymoshenko be imprisoned. In 2011, his rival was sentenced to seven years in prison for abuse of office for signing the 2009 gas deal with Russia. The trial is condemned as politically motivated by Western leaders and the Ukrainian opposition. “Most people did not suspect that to put Tymoshenko in jail would be so important for Yanukovych, and no pressure, either from abroad or inside Ukraine, will make him change his mind,” Karasiov says.

Other opposition figures have also become targets of the administration’s intolerance for opposition leader. Ex-Interior Minister Yuriy Lutsenko is in prison, while other members of Tymoshenko’s government, as well as her husband, have sought asylum abroad. “The courts have remained dependent … Moreover, the constitutional right to free assembly is violated by courts, who, in 80 percent of cases, ban assembly without legal reasons,” says Yevhen Zakharov, head of the Helsinki human rights group in Ukraine.

Kyiv Post staff writer Svitlana Tuchynska can be reached at [email protected].