This spring, Gennadiy Kanishchenko, the owner of a small bar in the heart of Kyiv, decided to take his own stand against Russia.

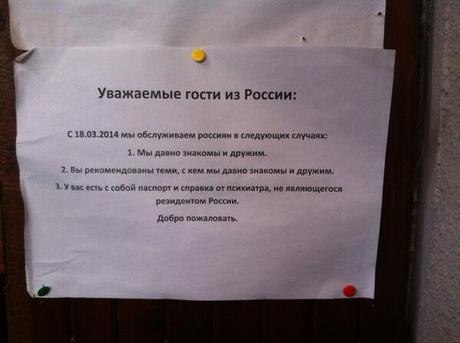

The notice outside Baraban (Drum) reads: “Starting from March 18, 2014, we serve Russians on the following

conditions: 1. We have been friends for some time. 2. You are recommended to us

by those with whom we have been friends for some time. 3. You bring your

passport with you and a note from a psychiatrist who is not a Russian citizen.”

This notice got noticed. The bar, opened 14 years ago by two

journalists, has built a following among the city’s press corps. With its

discrete but central location off the main Khreshchatyk Street, it became a popular

venue for free debate during the 2004 Orange Revolution. During the 2013-2014 EuroMaidan Revolution, the bar served free coffee and tea to activists, and

still does.

Since assuming ownership two years ago, Kanishchenko says he has tried

to retain Baraban’s open-door policy. However, recent events have him reviewing

his bar’s policy.

“Russians have changed under

the influence of state propaganda. They believe we are fascists and

nationalists. We obviously don’t understand each other any longer. Any attempt

to discuss the current situation leads to nowhere. They refuse to consider our

arguments,” he says.

Reaction from Baraban’s clientele has been overwhelmingly positive. When

the notice was posted to the bar’s Facebook page, it was “liked” more than 300

times. One user commented: “Cool. I’ve never been to your bar but after seeing

that notice I’m convinced it’s worth visiting.”

Others have been more hesitant. Dima Borisov, a restaurant owner who

knows Kanishchenko well, disagrees. “It’s not right to put up such a sign. We

should not single out one part of society,” he says.

Borisov, who owns a chain of establishments in Kyiv, believes little has

changed in the attitude of Kyivans towards Russians. “The atmosphere has always

been tense, ever since the breakup of the Soviet Union. The recent crisis has

simply brought many suppressed feelings to the surface,” he says.

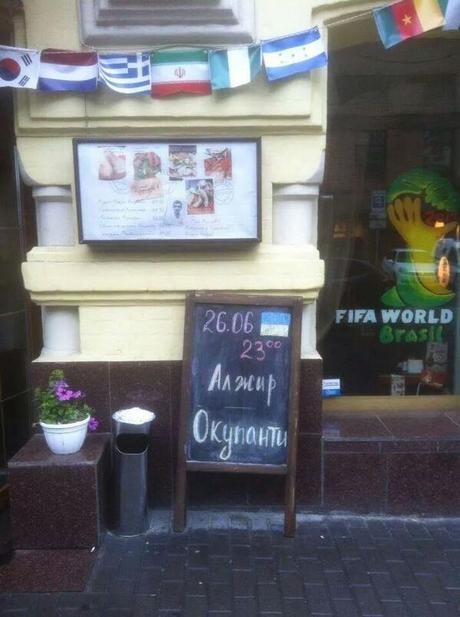

This much was obvious during the recent World Cup football championship

in Brazil. One Kyiv bar advertised Russia’s final group-stage match “Algeria

vs. Occupants.” Another popular venue hung the flags of each participating

country from its ceiling – only the Russian tricolor was missing. Staff said

customers had torn it down.

Jokes and innocent pranks at the expense of Ukraine’s eastern neighbor

disguise broader and deeper tensions.

On April 24, an exhibition in Kyiv saw three men dressed as

stereotypical Russians placed in a cage posted with signs saying “Beware of

Occupiers” and “Please do not Feed.”

Many Ukrainians, meanwhile, continue to actively support a boycott of

Russian goods launched in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March.

It even has its own smartphone application.

The reaction goes both ways.

A survey by Russia’s Fond Obschestvennoe Mnenie (FOM) in early July showed that

62 percent of Russians consider Ukraine an enemy, second only to America. And recent polls by the

Moscow-based Levada Centre reveal two-thirds believe the rights of Russian

speakers in Ukraine are being suppressed.

But even in Ukraine, the atmosphere of mistrust has not gone unnoticed

by Russians.

Journalist Gregory Kuznetsov, a Russian with a Ukrainian wife who has lived in

Kyiv for five years and has permanent residency in the country, says the new

chill has been felt by Russians.

“If I didn’t have a

residency permit here I’d have a big problem. Since the crisis began, it’s

become very hard being a Russian citizen in Ukraine. You never know if they’ll

let you return to the country after a couple of weeks spent back home,” he

says.

Like other foreigners, Russians are allowed to stay in Ukraine without a

visa for a maximum of three months. Many used to cross the border back into

Russia once this period had passed and re-enter Ukraine with a new stamp

permitting another three-month stay. This is no longer possible since the

EuroMaidan Revolution, Kuznetsov says, and policies have grown more stringent

since the conflict in Ukraine’s east began.

“Since the start of the

conflict, the border service has paid special attention to males aged 18-60,”

he says, adding that a number of his friends have been denied entry.

Kuznetsov says he has not personally experienced any hostility. He tries

to visit his ill mother in Moscow regularly, though work commitments have

recently kept him in Kyiv. Now, with free time on his hands, he admits he is delaying

the trip.

“I don’t really want to go there,” he says. In recent weeks, he has had

some uncomfortable exchanges about the Ukrainian crisis with friends back home,

many of whom refuse to accept his version of events. He fears the gap between

the two nations is only set to grow.

“Russians and Ukrainians

have always had a similar mentality. We share the same history, we watch the

same films, we read the same books as children. But if Russia continues in the

direction in which it’s heading, a civilizational rift will certainly develop.

Ukraine is moving towards Europe, and Russia is clearly moving in another

direction,” he says.

Kyiv Post staff writer Matthew Luxmoore can be reached at [email protected] and on Twitter at @mjluxmoore.