DNIPROPETROVSK, Ukraine – On a dusty, pockmarked highway on the southeastern border of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, some 20 scruffy fighters from Ukrainian volunteer battalions stand guard at a newly erected block post, scrutinizing vehicles coming from the separatist-controlled regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. License plates beginning with “AH” (Donetsk) and “BB” (Luhansk) are what they are on the lookout for.

The position is not only a checkpoint, but also it marks what has become the new, de facto border that divides the separatists’ enclave – which Kyiv has granted special status – from the eastern limits of Ukrainian-controlled territory.

“We have conflicts with the central authorities and ministries. They live in a virtual world. They don’t understand the real situation,” said Svyatoslav Oliynyk, a Dnipropetrovsk Oblast deputy governor responsible for military preparation.

Looking over a map on a table inside his office, Oliynyk pointed to red markings, indicating the locations of other block posts, fortified with steel tank traps, cement slabs and deep trenches.

Dnipropetrovsk, the regional center, is Ukraine’s third largest city with a million people and now the jump-off point for soldiers and supplies headed to the front lines. A predominantly Russian speaking region, it is an important industrial hub and home to Yuzhmash, the Ukrainian rocket manufacturer.

Also, Dnipropetrovsk is part of what separatists in the east, as well as Russian President Vladimr Putin, have deemed Novorossiya, or New Russia, the czarist-era name for modern-day southeast Ukraine. But since attempts here to spark a separatist uprising like those in neighboring Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts last spring failed, it has become a burgeoning center for pro-Ukrainian sentiment and preparations for the war effort. Blue and yellow national flags line the streets and fly from the tops of the city’s tallest buildings here.

With the conflict in such close proximity to Dnipropetrovsk, the political and business leadership has taken to organizing war preparations themselves to support the defense of the region.

The oblast has two charity funds that local businessmen contribute to get around the stifling Ukrainian bureaucracy and help the war effort. One is for military supplies and equipment and the other is to help victims of the war.

Despite obvious concerns and potential conflicts of interest, Oliynyk said the government cannot help but turn a favorable eye to those who donate to the funds and help with the war effort.

The new block post was built just a few weeks ago with money from the military fund. Along the road there is a shelter dug into the ground erected out of cement blocks and covered with sandbags. With the war dragging on and winter nearing, the fighters manning the region’s borderline will soon need cold-weather clothes and the bunker will need to be insulated. The fund will help with all that.

Most of the men who stand guard there are locals, with the exception of one Security Service of Ukraine official, who is from Ternopil, a western Ukrainian oblast capital. They range in age from their early 20s to 60s..

On Sept. 19, about a dozen fighters from Dnipro and Donbass battalions worked the block post with a handful of local police and some fighters from the Sicheslav Battalion. One masked man from the nationalist group Right Sector joined them, checking cars leaving Dnipropetrovsk past a cement block adorned with the words, “Knife the Moskali,” a derogatory term for Russians.

Patting the side of his automatic rifle, a beefy, elderly fighter with a neatly trimmed mustache who goes by the nom de guerre “Ded,” meaning grandfather, said: “We are ready if the terrorists’ spill onto our land.”

With the war so close and Kyiv so far away – both geographically and in mentality –local authorities, under the leadership of the oblast governor, the billionaire oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskyi, have increasingly taken matters into their own hands. One of those areas has been the exchange of war prisoners.

“We waited for the central government for a long time, but no one wanted to deal with it, so we set up contact ourselves” with the prime minister of the Donetsk People’s Republic and organized an exchange of prisoners,” Deputy Dnipropetrovsk Oblast Governor Borys Filatov told the Kyiv Post in an interview.

Almost daily, newly released Ukrainian fighters taken prisoner by the separatists are brought to the Dnipropetrovsk Regional Administration and debriefed before being taken home. Inside the building’s elevator just before midnight on Sept. 18, one fighter who had been taken captive by the separatists spoke on the phone with his father in Kyiv after government-appointed hostage negotiator Vladimir Ruban brokered a deal to free him. “Dad, it’s me. I’m OK. I’m free,” he said. “I’m with Ruban. He’s taking me to Kyiv. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

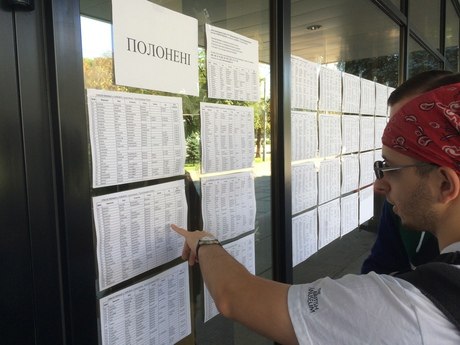

But many families still await the return of their sons and daughters, hundreds of whom are listed on sheets of paper hung near the administration building’s entrance. According to the lists, 422 soldiers remain missing and 803 are still being held in captivity. The lists are updated and new ones posted each morning. In some cases, when the lists have not been updated, soldiers who were freed and returned to the building have written, “I am alive!” next to their names.

“When we were organizing the exchange of prisoners, the separatists came and we talked. It’s clear they are difficult to deal with, some have blood on their hands so to speak, but we need to talk. And even the separatists understand they have no way out. They understand that Russia will eventually just liquidate them or make them into a full puppet,” Filatov said, highlighting the pragmatism that has come to define wartime Dnipropetrovsk.

The city has also become a recovery center for soldiers wounded at the front. National Guardsmen are treated at the city’s military hospital, while battalion fighters and policemen are treated at separate public hospitals in the regional capital.

Inside Ilya Mechnikov hospital, several fighters from the Donbas Battalion are recovering after sustaining gruesome injuries during the bloody fight for Ilovaisk, a strategically important city in Donetsk Oblast, in late August. At least 107 Ukrainian fighters were killed in action when separatist forces and Russian soldiers, according to Ukraine’s Defense Minister Valeriy Heletey, surrounded them and bombarded the group with rocket fire as they tried to escape through a corridor designated as a safe passage out.

One fighter, who gave only his first name, Eduardo, told the Kyiv Post from his hospital bed that a bullet flew through his right upper arm and then struck him in the jaw, knocking out several teeth and part of the roof of his mouth, during the infamous battle. His face was still swollen and daubed with green disinfectant as he reminisced with friends from the battalion.

He chatted with Alexander, another battalion fighter, who was hit in the neck by shrapnel from a rocket. Removing the white bandage taped to his throat, he showed the freshly stitched wound.

“I was very lucky,” he said.

Also in the room was their commander, known by his men as “Fagot,” a type of Soviet anti-tank missile.

“I used to think, if something happens to Ukraine only Russia will help,” he said. “The same language and same weapons. I just don’t understand.”

Fagot said he has recently been released after being held captive by Russian soldiers who treated him well at first, because he had been in officer in the Soviet army. But later they turned him over, along with several comrades, to separatist forces after promising they would be transferred to Ukraine authorities.

Recalling his time on the front line, Fagot tears up and pulls his sunglasses over his eyes when talking about a young man from his hometown of Bila Tserkva, near Kyiv, who left three children and a wife behind when he was killed by a grad rocket near Donetsk.

Stories like these are common in Dnipropetrovsk.

“Everyday we deal with dead soldiers, injured soldiers, prisoner exchanges while Kyiv just dealing with elections,” said Filatov.

Filatov said the realities here are not understood in Kyiv. However, he is also thinking of elections, announcing on Facebook that he will run for parliament in next month’s election as an independent.

In discussing the motivation behind the beefing up of defenses here, Filatov said: “When you sit down and see that there isn’t an army, you know you have to do something. You have to organize units.”

“If we hadn’t done that ourselves, the (separatist) DNR would already be here,” he added.

Editor’s Note: This article has been produced with support from www.mymedia.org.ua, funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark and implemented by a joint venture between NIRAS and BBC Media Action, as well as Ukraine Media Project, managed by Internews and funded by the United States Agency for International Development.