The government decided

to create a single electronic system of interaction with

citizens and transfer the key administrative services to the

Internet. This is where the process halted.

E-government

has long been a reality not only in distant

countries like Singapore, the US or Sweden, but also in

former Soviet countries, such as Georgia,

Moldova or Estonia.

Back in the 1990s these

nations realized that transition to an electronic system of

procurement could save up to 50 percent of

the typical expenses from

the state budget. Due to

e-procurement, Georgia saved $200 million in just

two years. Moldova is currently actively advancing the idea of

a single datacenter, on the basis of which government agencies are

providing unified services to citizens.

Ukraine, however,

is trying to live by old habits. The latest promise the government

made to the world community is Ukraine’s accession to the

international Open Government Partnership Initiative. It was launched

in September 2011 in order to introduce standards of openness and

transparency of governments’ actions. To date 57 countries, Ukraine

included, have joined the initiative.

The Ukrainian

government adopted a national action

plan for the implementation

of the open government

idea with the following priorities:

a) community participation;

b) counteraction to corruption;

c) access to information;

d) administrative services; and

d) e-governance.

But again, there has been

no progress beyond adopting the action plan.

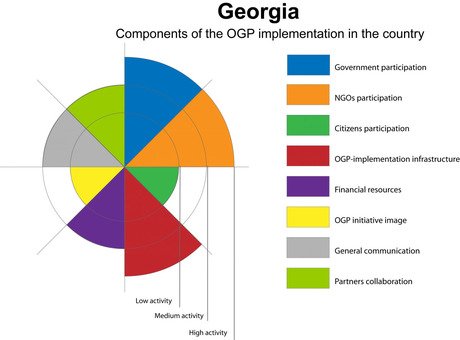

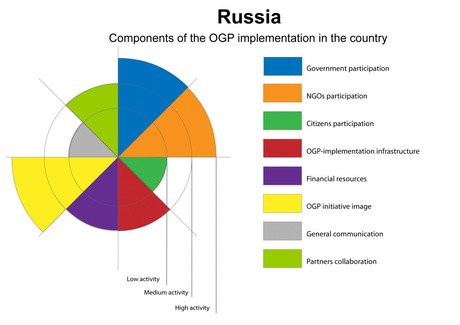

Can it be done otherwise? The

experience of our neighbors shows that it can. Jointly with their

partners in Russia, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moldova,

Transparency International Ukraine analyzed the government’s

actions of implementing the open government plan.

Their attention was centered on

government participation, nongovernmental

organization participation, community participation,

implementation infrastructure, financial resources, image of

e-government, general communication, and

partners engagement.

It’s not difficult to see the

interdependence of the indexes of infrastructure development of

e-governance and the level of a government’s engagement in its

implementation. The high political will in all the countries, except

for Ukraine, is also obvious.

There’s something we can learn from

our neighbors – in Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moldova.

E-governance is working.

In Georgia, public procurement is carried out online. In Armenia, an

interactive budget has been adopted; the sessions of the government

are transmitted online.

Moldova’s leadership cherished an

ambitious plan to complete an e-transformation by 2020, i.e., to

switch over to a total electronic form of reporting.

In Russia, the idea

of e-governance is becoming fashionable due to the government’s

propaganda machine and the support of key media people behind it.

In Ukraine, Russia and Azerbaijan, the

idea of e-governance forced the authorities to

greater interaction with the public.

Incidentally, participation of

non-government sector is practically the only

indicator in which Ukraine has achieved a high score. Because of

active NGO involvement, 80 percent of the national

action plan

consists of their proposals.

In all the countries

we reviewed the citizens know very little about the e-governance.

In Armenia, 5 percent of the population has some

knowledge of the project, for instance.

Some countries are

taking actions to increase public awareness and engagement. Georgia

is holding student competitions to improve the action plan, while

Moldova is engaging senior students for internship at government

departments for e-transformation.

In Ukraine there are four key dangers

in implementation of

e-government plan:

Lack of an efficient coordination

mechanism between the government agencies responsible for the Open

Government Partnership Initiative and between the government

and NGOs.

Inadequate quality of enacted

legislation.

Insufficient budget funds for

implementing the “electronic governance.”

Deadlines are

impossible to observe due to the highly bureaucratic process

of decision-making that causes substantial delays.

To advance the

implementation of e-governance, both the authorities and the NGOs

need to create an efficient permanent mechanism

for communication. Also, the government

should get serious about control and management of e-governance

action plan. The government is not experienced enough in

conducting a transparent dialogue with NGOs and needs support and

recommendations in establishing the much-needed

communication mechanism.

Oleksii Khmara is the president

of Transparency International Ukraine. Olga

Tymchenko is communications

department head

of Transparency International Ukraine. Olena

Kifenko is head of fundraising and

the international relations

department of

Transparency International Ukraine.