See the investigation’s extended version here.

As an old saying goes “nothing lasts longer than the temporary.”

The war in Donbas, which began as an armed insurgency led by a paramilitary company in Sloviansk, transformed into a type of trench warfare lasting for more than five years by now. Although the variety of challenges Ukraine is facing is broad, it is the unresolved conflict that became the central issue according to the Ukrainian opinion polls prior to presidential elections.

Volodymyr Zelensky appealed to this sentiment in the pre- and post-election period by publicly raising hopes to end the war within his presidentship. As he has put himself on July 8th: “I want to hope that in a year we will no longer have this war”. Yet quick results demand quick actions and with the 100 days bar crossed in August, it appears to be the right time to check how much difference was Zelensky’s team able to bring to life at the contact line in Donbas.

Mapping words to actions

Although the new president was naturally limited in tools before the new government was appointed on August 29th, Zelensky’s team tried to implement measures, which could potentially have a positive impact on security along the contact line. Among the most notable ones were the following:

- June 29, 2019: Disengagement of forces at Stanytsia Luhanska completed

- July 29, 2019: Recommitment to a ceasefire agreement comes into force

- August 5th, 2019: Change of military command, a new commander of Joint Forces appointed

- September 7, 2019: Exchange of prisoners between Russia and Ukraine

Of all four events, it was the recommitment to a ceasefire agreement which could have the most decisive impact on security along the contact line. Under the previous government, recommitments were numerous in the count but neither of them was long-lasting and if the new administration could reduce the number of violations done by heavy arms, that would already be a big improvement of security at the contact line.

To see whether the actions of the new administration were effective, the author has digitized reports of the special monitoring mission (SMM) deployed by OSCE to supervise adherence of the parties to the ceasefire agreement. The reports contain a daily number of ceasefire violations witnessed either by the OSCE crew in person or with distance controlled tools like cameras and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV).

The OSCE reports are not the only source of the data on ceasefire violations. Similar data are delivered by the government (Joint Forces Operation and the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine) and separatist (Militia Forces) press offices. Although the number of reported violations by OSCE does not match exactly with the numbers reported by opposing sides and the quality of reports is sometimes questioned by the locals and journalists, this column uses OSCE reports for the investigation.

Despite the drawbacks, the author finds OSCE reports the most reliable source among available ones due to the impartiality of OSCE, the constant presence of the crew in the conflict zone in the government- and separatist-controlled areas, and an established process of collecting information since the eruption of the conflict. Note, however, for completeness that the OSCE reports tend to show more ceasefire violations after the ceasefire agreements compared to data of Joint Forces Operations.

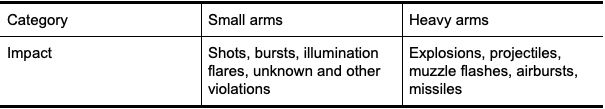

Each observation in an SMM report contains information about the number of recorded violations, type of evidence, location, and – whenever determined – a type of weapon it was shot by. The collected dataset contains 235 days of observations starting from January 8th, 2019 and ending with August 30th of the same year with a split by presumably heavy and small arms violations, where the classification was performed as follows:

Classification on small arms/heavy arms violations.

What numbers tell

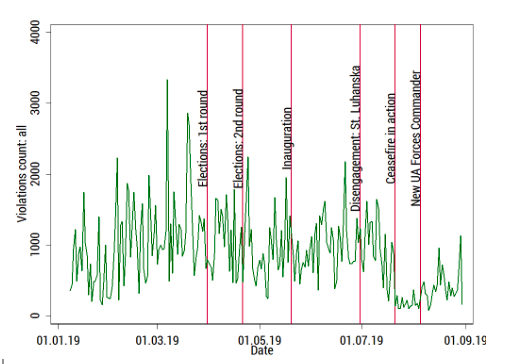

Summing up all violations unconditionally by each day generates the following distribution over time:

Figure 1 allows drawing a number of general conclusions about the conflict dynamics in Donbas. First, a full ceasefire never happened throughout the observed period neither under Poroshenko, nor under Zelensky; the overall daily minimum was recorded on August 10th with 79 violations per day (74 “small arms” and 5 “heavy arms” violations). Second, long periods of escalation are almost as rare as long periods of de-escalation.

Typically, the intensity “jumps” from escalation to de-escalation and vice versa. If one takes a 33% increase/decrease in conflict intensity as benchmarks for escalation/de-escalation respectively, one would count 65 episodes (day-over-day changes) of maintaining a status-quo, 110 episodes of a “gradual” switch, and 56 episodes of a rapid switch from de-escalation to escalation or vice versa.

Considering the impact of the newly elected president, the chart provides a mixed account. Although both sides claimed that the ceasefire agreement was almost immediately violated, one can notice a rapid decline in the number of violations straight after a recommitment came into force on July 21st.

Yet, the period of a comparatively “mild” warfare with 100 to 300 violations per day did not last longer than two weeks. On August 6th – the day when four marines of the Ukrainian army were killed – the number of violations crossed 400 records with almost 500 following on the next day. From there on, the conflict intensity started to rise again with a tendency to return to it pre-recommitment levels.

The “turnaround” however, mainly applies to the “heavy arms” used as the “small arms” violations were less affected by the agreement on July 21st.

the upper bound of the quartile range of the post-ceasefire “heavy arms” violations does not exceed the median value of the pre-recommitment period under Zelensky. Albeit “small arms” violations have decreased, the pre-recommitment and post-recommitment distributions still overlap significantly. This outcome resembles the pattern under Poroshenko’s government during his last ceasefire recommitment on December 29th, 2019.

The way out

What Zelensky’s administration is probably facing now are the consequences of a commitment problem: an incentive to violate an agreement to obtain short-term gains. Whenever one side withdraws its armed forces, it leaves a contested territory unprotected and reduces the costs of a military advance by an opponent.

The inability to stop active warfare at the contact line resembles the problems of conflict resolution in other war-afflicted countries. History of conflicts across the world over the last century shows that peaceful conflict resolutions are exceptions, not a rule. Unfortunately, those one, which were reached do not last long: most post-conflict countries slip back to war after the ink of the peace agreements has barely dried.

There are two major impediments for reaching peace with separatists. Even if the command of separatists is centralized, there is no guarantee that the implementation would not be undermined by spoilers – individuals or parties, who exploit the war for extracting rents or obtain power – on the local level. The other one is an asymmetric distribution of coercive power in favor of the government after the conflict ends. Separatists know that the very moment they lay down arms, there are barely any obstacles for the government forces – especially in the country with weak institutions – to violate the agreements ex-post.

Thus, ceasefire agreements with no external involvement are inherently unstable. Although OSCE acts as a broker in the negotiations between the separatists and the government in Ukraine, its mandate is limited. Neither can it punish ceasefire violations, nor can it establish arms control. Since pursuing the rebels to give up the stock of weapons directly is barely feasible in the near future, the negotiations within the trilateral group leave little room for optimism.

Fortunately, direct methods are not the only ones. In that respect, a UN peacekeeping operation is a viable alternative because it assures the highest level of legitimacy and credibility for both conflict parties and the international community. And it is the legitimacy of peacekeeping forces in the “buffer zone” – not guns and bullets – which are going to increase costs of advancing at the contested territory after withdrawal of armed forces and overcome the commitment problem.

Although the idea of a UN peacekeeping mission is recurrent, many find this option unfeasible in practice. The perceived feasibility, however, relies on assumptions made about the true strategic goals pursued by Moscow. If the Kremlin uses unrecognized republics as a mean to have constant leverage over the Ukrainian government(s), then the peacekeeping mission will never be effective. Yet in that case any negotiations are meaningless and diplomacy is not the right tool to resolve the conflict.

A Ukrainian soldier engages the enemy lines in the war zone near the town of Novoluhanske, eastern Ukraine, on June 14, 2019. Outgoing shell casings has broken the camera’s glass filter. (Volodymyr Petrov)

The other assumption could be that the Russian government is indeed interested in a conflict resolution. It is most likely then that Moscow is pursuing a setup which would avoid a scenario that happened in Srpska Krajina, when Croatian military overran the separatist forces despite a UN mission on the ground.

In that case, deploying a peacekeeping mission in a stagewise manner – starting with the contact line and gradually extending its presence farther to the East – is a scenario that could align the incentives of all conflict sides. Separatists and Moscow will not have to face an immediate increase of a risk of a military operation – the option sporadically (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) discussed in the context of a conflict, while Kyiv will be able to gradually restore control over the whole Russian-Ukrainian border and set up conditions for an organized post-conflict transition.

One has to admit that the outlined approach is technically complicated: it will most likely be the biggest peacekeeping operation in UN history in terms of deployed forces and territory monitored. It would also face a risk of being stuck at the early stage without proceeding to the full restoration of the border control. If these risks, however, materialize the government of Ukraine will always have an option to withdraw the consent and come back to the present setup.

And in case Moscow objects the proposal, it would hit the diplomatic reputation of Russia, while Kyiv would lose nothing. This approach demands compromises from all involved parties. Yet diplomacy is all about finding compromises in the realm of the possible. Since there are voices in Russia that support the idea in principle, there is a chance for diplomats to achieve more.

As long as Zelensky and his team are committed to end the war, they better at least try this chance because otherwise, guns will continue to speak. Just as they are right now.