From The Battlefield is an exhibition program that has united Ukrainian and Dutch artists in the Netherlands city of Tilburg. Maria Vtorushina, curator and researcher of queer culture, is one of the millions of Ukrainians fleeing their houses after the mass Russian aggression. She has moved to the Netherlands. Like many of her colleagues, Maria has continued her practices in order to tell Europeans what her compatriots are going through.

The main characteristic of a civilized society today is understanding the value of a person, of every individual. The right to define personal identity — complicated, tender, variable — is crucial for appreciating human rights in the XXI century. New generations, people of the digital age, naturally grasp tolerance, inclusion, the theory of neurodiversity, and ecological relations. New meanings can arise in comparing a person to a symphony, which is impossible to perceive as a single melody, abstracted from others, as Yukio Mishima wrote in his play Madame De Sade.

When evolutionary breakthrough happens, everything traditional, outdated, and degrading will inevitably try to defeat reality and destroy the sprouts of change. Thus, absolute monarchies attempted to choke revolutionary ideas in France. Thus, farmers destroyed the first tractors, seeing machinery as a threat to their existence (Russian writer Leo Tolstoy supported this movement). Thus, the USSR tried to smash “Socialism with a human face” in Prague using its tanks and the will for freedom in Vilnius. Thus, France, the U.S. and China tried to keep Vietnam as a colony.

The reaction didn’t stop scientific and technological progress; neither did it stop the development of civil society nor anti-colonial liberation movements. It may seem that the latter could also refer to the current Ukrainian resistance against Russian aggression. But this war is much more than just that. We are dealing not with the last waves, spread by the old dying empire, but with the actual storm, which brings a new understanding of human freedom and dignity. Attacked by this concentrated retrograde regime, Ukraine became the epicenter of this storm. This confrontation is between diversity and depersonalization, transparency and post-truth, emancipation and unification.

Katya Buchachka, “Alarm Tablecloth” (2022), Chantal Renz, Tamara Turlyun, Andriy Lyashchuk “One Day You Will Grow Back Your Thumb” (2022). General view of the exhibition “From the battlefield” at the SEA Foundation. Photo provided by the organizers.

With support from the SEA Foundation, Maria Vtorushina has highlighted several personal stories from this battlefield, initiating the direct interaction between artists from Ukraine and the Netherlands. The curator amplifies through the following: “Ideas of the brightest theorists seem not humane enough to establish the productive dialogue between the so-called Western world and the current frontier of the war. Therefore, From The Battlefield will address no theory. Through collaborations and artistic production by Ukrainian and Dutch participants, we want to capture a specific time and space where violence and disruption prevails. How do people live through a war whose will for freedom is so powerful? How to organize a safe space so that hope could sprout again? ”

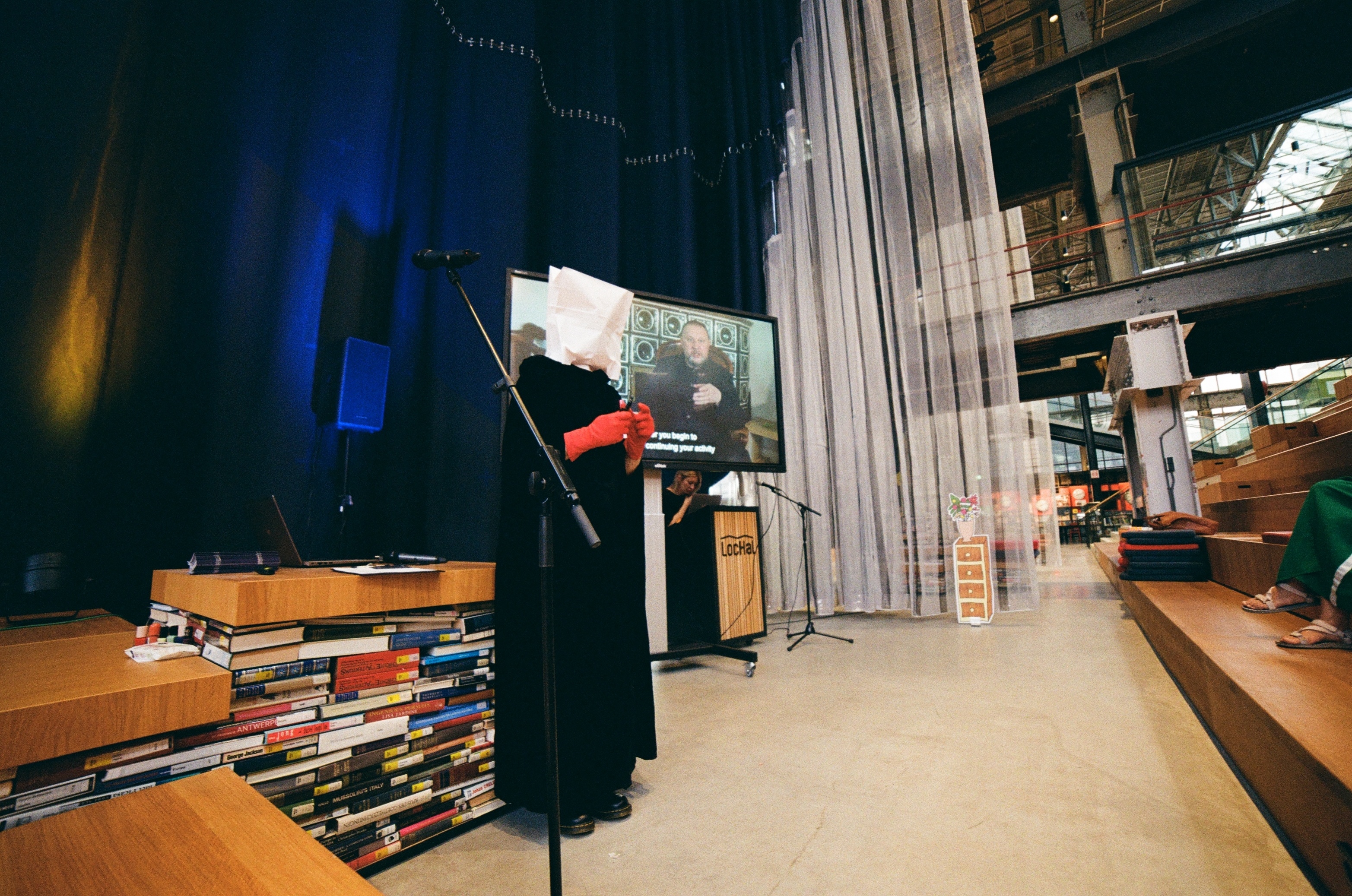

The exhibition at the SEA Foundation was accompanied by a public program at LocHal Bibliotheek and the De Pont Museum. As part of the project, a screening of Homewards, a film directed by Nariman Aliev, telling about the fate of a Crimean Tatar family, separated by the Russian annexation of Crimea, took place at Cinecitta.

It is obvious that Russia is waging war to eradicate national identities. The Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians are the primary targets. But the final aim of the Moscow regime is complete negation of any personal identity. Bombardment of Ukrainian villages and cities and crimes against humanity in occupied towns is synchronized with increased repression inside the aggressors’ state — suppressing freedom of speech, cultural and religious rights of indigenous peoples and small communities, eradication of any opposition, and persecution of members of LGBTQ+. People are sentenced to prison because they have reposted stuff on social networks or for publicly displaying posters with quotes from the Bible.

“… Don’t be the other, be the one.

Stand firm.

Take off your clothes.

Take the step.

Take off your clothes.

Learn. Listen. Walk. Crawl.

Eat. Listen. Sleep. Fuck.

Drink. Listen. Shit. Piss.

Fall. Listen. Walk. Fall…”

These are lines from the poetic performance of Nick J. Swarth And The Nail Polish Is My Weapon. Why The Rainbow Doesn’t Fit Into The Bear’s Mouth, written for the project From The Battlefield. This performance is a result of our dialogue. In a series of online conversations, I shared with the artist my individual experience of living through war, and the cultural and historical analysis of the reasons and consequences of Russian aggression. Nick wrote a poem in which the world of colorful variety is attacked by a brutal force willing to reduce everything to black and white, to gray and red.

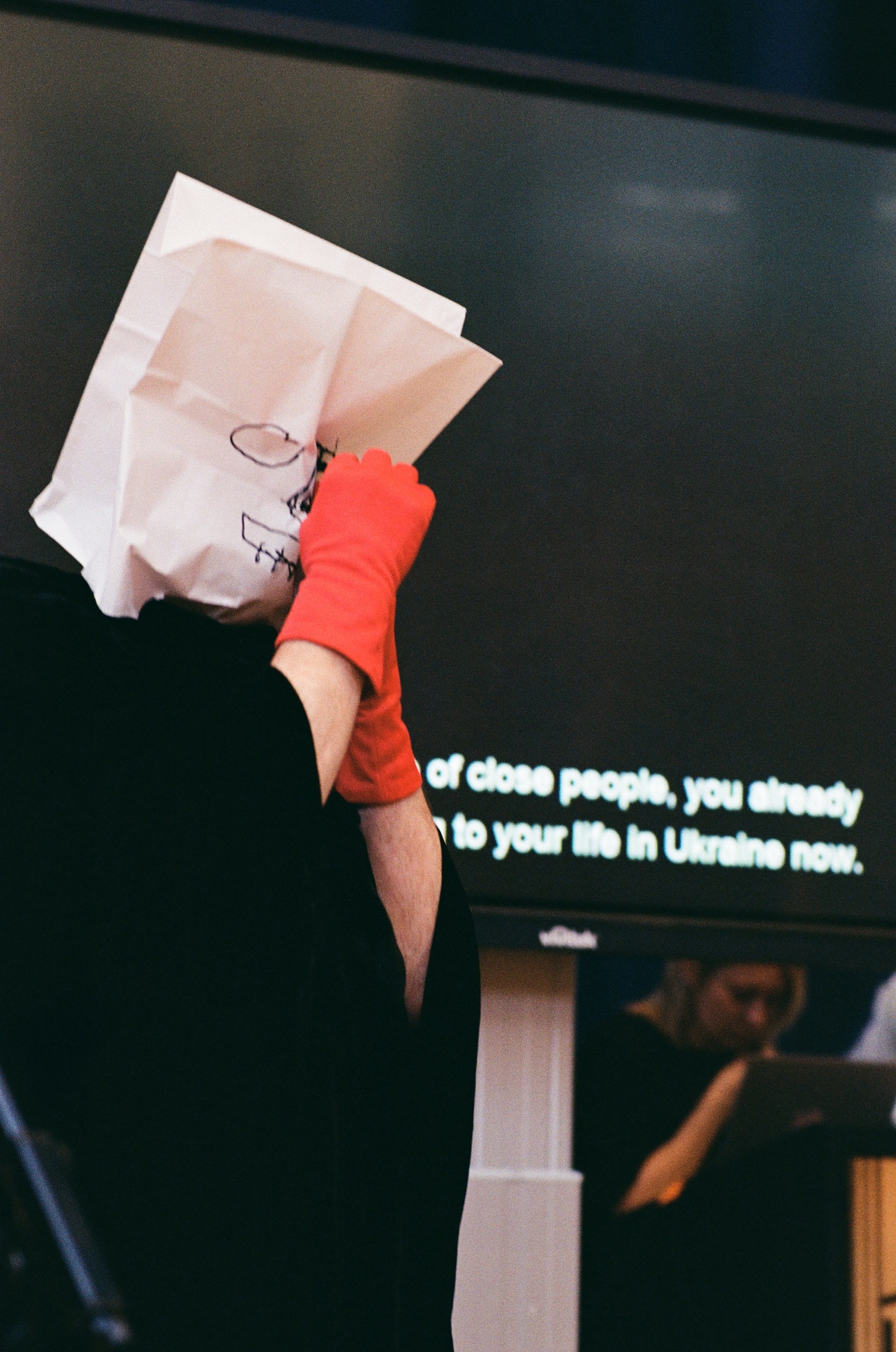

Nick J. Swart “And nail polish is my weapon. Why the rainbow does not fit in the bear’s mouth” (2022). Performance at LocHal. Photo provided by the organizers.

A bear, a recognsizable symbol of Russia, tries to devour reality. But only faceless things fit into his mouth. A rainbow breaks the darkness inside the bear’s stomach. “I am different, I speak without fear, and my nail polish is my weapon,” Nick J. Swarth sums up. The brightness of the nail polish becomes the symbol of personal resistance to captivity, the nurturing experience of staying an individual in a situation of dehumanization. The artist clearly visualizes this resistance in the performance: he dresses a square paper bag on his head. Blinded, in a rush, he tries to draw a face on the bag, saving himself from depersonalization.

In Katya Buchatska’s Alarm Tablecloth, evidence of humanitarian catastrophe reveals itself through everyday experience. Because of the war, the artist had to go to Lviv, where she stayed with her distant acquaintances.

Leo Trotsenko, “Alarm tablecloth by Katya Buchatska. From the series “Replicas and Differences”, (2022). Alevtyna Kakhidze, Untitled (2022). From the From The Battlefield exhibition at the SEA Foundation. Photo provided by the organizers.

To help Katya, a displaced person, someone gave her an old tablecloth with yellow marks and some handmade embroidery. “This evening was the most difficult: I was safe in someone else’s apartment and couldn’t save anyone. The only thing I had left from my past was a backpack with my belongings; I didn’t pack it as my emergency bag,” the artist recalls. So Buchatska laid out the things from her bag on the tablecloth and enclosed the contours.

Leo Trotsenko paid homage to this work in the Replika And Differences project. The artist embroidered the same contours on a rose fabric. Here, embroidery addresses self-soothing rituals through traditional household practices from past centuries. It tames the feeling of helplessness and saves one from panic.

Another work by Katya Buchatska shows that people traumatized by war and those who lead peaceful lives perceive the same visual information in two different ways. The artist captured a scene on Venice Lido beach that she chooses not to comment on: a seemingly breathless human body lies on the sand, while one can observe the contemporary ships sailing far away. Although Europeans don’t feel bothered by what they see, Ukrainians associate this image with the tragedy of Mariupol or rocket attacks on Odesa; the person seems to be a victim of shelling or a mine explosion.

Alevtina Kakhidze adapted her long-term action Seeds Of Ukraine to new realities. Right from the start of the war, the artist’s mother had lived in that part of Donbas that was occupied by Russian troops in 2014. While visiting her daughter in Kyiv, Alevtina’s mother bought seeds of flowers and vegetables that disappeared from sale in the Russia-supported, self-proclaimed Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics.

Alevtina Kakhidze. “Seeds of Ukraine”. Kiosk (2019). From the From The Battlefield exhibition at the SEA Foundation. Photo provided by the organizers.

In 2019 Alevtina’s mother died at a checkpoint on a non-controlled part of Ukrainian territory. In her memory, the artist brought to Zero, a border between the controlled part of Ukraine and territories occupied by Russia, a kiosk with seeds that people could take in exchange for their stories, drawings, and small souvenirs from Donbas. From February 24, 2022, Ukraine became isolated as a battlefield, and Alevtina changed the project to Seeds Of Europe. The kiosk is accumulating seeds in the Netherlands to bring to Ukraine in exchange for stories, drawings, and little artifacts. Under the threat of global famine due to difficulties with the export and further production of Ukrainian food caused by Russian bombing and the blockading of Ukrainian ports by Russian occupiers, Alevtina Kahidze’s work takes on a new scale. We see how small private initiatives can manifest the international agenda.

Kakhidze’s artistic statement was supported by Dutch artist Roos Vogels. In her practice, Vogels researches the evolution of plants from growth to decay, aiming to reveal the intermediary between blooming and death and translate the rhythmic changes of nature as a message to humanity.

Project One Day You Will Grow Back Your Thumb — is a fruit of collaboration between Ukrainians Andriy Liashuk and Tamara Turliun and the Dutch artist Chantal Rens.

Tamara Turlyun, Andriy Lyashchuk “One Day You Will Grow Back Your Thumb” (2022). Photo provided by the organizers.

After the bombardment of Kyiv, artists Tamara Turliun and Andriy Liaschuk began to make wooden birds to sell in support of Ukrainian defenders. In April, Liaschuk cut off his thumb while crafting. Together with Turliun, they developed thumb prosthetics from objects that they found: plastic from a coffee machine body, fridge radiator, parts from a track light, rubber from a GP5 gas mask, etc. This prosthetic unexpectedly proved ergonomic, and the artists started to work on multiple productions using 3-D technologies. What followed these events was a dialogue with Chantal Rens in social media, guided by objects randomly found by the artists, that were associated with the traumatic experience and the will to overcome it. The result is the Leporello, published in Tilburg with a print run of 500 copies.

Personal experiences, individual tragedies, facing challenges and overcoming obstacles despite the everyday reality of war, nervousness from air raid sirens, exhausting news from the front and occupied territories in unison forge empathetic art. This type of art causes a persistent aversion to war as concentrated anti-humanity. To protect their homes from this threat, Europeans have no alternative but to contribute to Ukraine’s victory and the complete demilitarization of the aggressor country. The bear must be repulsed and forced to settle forever in his den.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and not necessarily those of the Kyiv Post.