“It is important to emphasize that [Peace Corps volunteers] will receive as much as they give, and perhaps more. I want to make it clear that when our Peace Corps volunteers go to other countries they will go to learn, not just to teach.”

— R. Sargent Shriver (1915-2011), the first U.S. Peace Corps director

I imagine sometimes how the world looked to the audience listening to the Peace Corps’ first director, Sargent Shriver, on March 24, 1961.

Just two months earlier, John F. Kennedy had taken the oath of office and become the youngest man to serve as president of the United States.

Shriver was in New York that day to celebrate Executive Order 10924, signed on March 1, 1961, which established the new independent agency and volunteer program run by the United States government. America was full of optimism but, amazingly, still somewhat modest about what the world could expect from its army of young volunteers, anxiously waiting to engage it.

When I landed at Kyiv Boryspil International Airport on Oct. 4, 2002, I was anxiously waiting to engage Ukraine.

Except for a few short road trips to Montreal during university, I’d never left the United States.

I was curious about my new home-to-be. I was a little intimidated by the prospect of the language and cultural barriers which laid ahead of me. But mostly, I was hungry.

My very first memory is trying to buy a Snickers from the coffee bar in the old Borispol.

I said Snickers.

The woman behind the bar asked: “Shto?”

I said Snickers.

She repeaed: “Shto?”

Two more rounds of this and the man behind me in line stepped up, pointed, and said “Sneakers,” with the appropriate roll of his “r”.

My first lesson: Sneakers, the Ukrainian Snickers (side note, I would later be told that salo was the Ukrainian Snickers). At that exact moment, I thought, “I’m never going to make it here.”

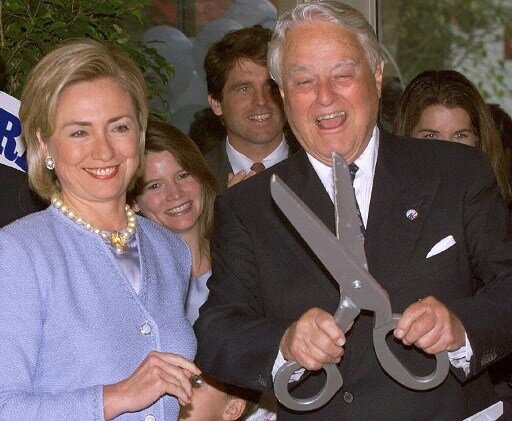

On Sept. 15, 1998, then-U.S. First Lady Hillary Clinton and Sargent Shriver prepare to cut the ribbon during the opening ceremonies of Shriver Hall in Washington, D.C. The new multi-purpose center was named in Shriver’s honor, the Peace Corps’ first director, from 1961-1966. (AFP)

In truth, I’m still not sure if I “made it” as a Peace Corps volunteer.

There isn’t a lasting institution or program in Ukraine because of me. There wasn’t a school full of children who spoke fluent, American-accented English after my two years of instruction. My formal impact is negligible if I’m truly being honest.

Ukraine, or more accurately Ukrainians, gave me much, much more than I gave them. My impact, I believe, was friendship and the trust and honesty which comes with true friendship.

Olia Mihailivna was my counterpart at School #1 in Kosiv, a small town of 8,000 residents in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, more than 500 kilometers southwest of Kyiv. Our relationship developed from a stiff professional acquaintanceship to a warm friendship.

Khoma, my best friend, quite literally shepherded me through the complexities of life in a small town, often over a beer and a cigarette.

There was the family who ran the local restaurant that treated me as one of their clan, welcoming me into the kitchen for family meals.

Nelya and Zoriana took pity on their teacher, who was only a few years older, and always extended invitations to go camping or hiking.

Oleg and Victoria were young parents and my adopted siblings.

Yuliya, my Chernivtsi “big city” sister and confidant, remains a close friend today.

American Dave Elseroad (right) with friends in Ukraine.

I think back to Shriver’s speech often and reflect on the fact that Ukraine gave me more than I gave her.

The Peace Corps and Ukraine changed my life. There is no other way to say it.

When I think of everything and everyone that I hold most dear today, almost all of those things are in my life because I served in Peace Corps in Ukraine. After returning to the US, I was fortunate enough to get a job working for a nongovernmental organization that ultimately sent me back to Kyiv, just after the 2004 Orange Revolution that brought Viktor Yushchenko to power and overturned a rigged presidential election.

While there, I accepted a chance dinner invitation at the home of a Peace Corps staff member and friend, Iryna, who serendipitously seated me next to my future wife. She was a Swiss graduate student, studying the role of civil society in the Orange Revolution. Within six months, we were married. This summer, we will celebrate our 15th wedding anniversary with our two children. Iryna and her daughter, Marta, remain family friends.

Serving as a Peace Corps volunteer allowed me to not only meet and fall in love with my wife, it allowed me to meet and fall in love with Ukraine. Like any great love, I’ve worked to give back as much as I’ve taken.

In the nearly 20 years since my service, I’ve devoted my career to working with Ukrainians to make Ukraine safer, healthier, and more peaceful. I’ve worked on weapons non-proliferation, tobacco control, road safety, and human rights.

But, like the Peace Corps, this work has meant that I’ve had the incredible good fortune to work with some of the greatest Ukrainians of their generation: advocates, future politicians, human rights defenders, civil society leaders, journalists, lawyers, academics, researchers, anti-corruption crusaders.

These are passionate and devoted servants to the idea that Ukraine can the country that Ukrainians deserve. It is a true privilege to count them as friends as they are also inspirations to me. I would not have these friends and these inspirations were it not for the Peace Corps.

So, for me, friendship and love are the lasting images of the Peace Corps.

If Shriver is somewhere keeping tabs on the great scorecard in heaven, I hope that I have done enough to give back for everything that Ukraine and Ukrainians have given me. They’ve changed my life.