More than 50 years have passed since his release from a Siberian labor camp but the smell still reminds him of the prison swill called balanda. A thin gruel made of komsa baitfish – not even cleaned – balanda was usually all he got to eat during of his nine years in the gulag. With a revanchist Russia changing the Perm-36 Gulag Museum from a memorial for the victims to a celebration of the jailors, it is worth remembering the decisive role that political prisoners – mostly western Ukrainians but also other ethnic groups – played in bringing the deadly Soviet prison system down after World War II.

My father, Myron Mycio, was one of them. He even plotted to hijack one of Josef Stalin’s slave ships.

In January 1948, a Soviet court sentenced him to 15 years of hard labor for the “counterrevolutionary activity” of being in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, known as UPA, and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.

He was 22. His story is a chilling illustration of why it’s wrong to close down gulag museums like it happened in Moscow this month. There should be more, not less of them, to remind humanity of the horrors that should never be repeated again.

For a year, they sent him from camp to camp in Russia’s northwest Komi region. In Ukhta, he cut trees. In Vorkuta, he built barracks. The stink of balanda followed him everywhere.

For decades, Gulag jailors mixed political prisoners with criminals as a form of intimidation. This worked with the pre-war “politicals,” mostly urban intelligentsia who were easily cowed. After the war, the authorities continued the practice, especially targeting Ukrainians – derided as Banderovtsi or Banderites, after OUN leader Stepan Bandera (1909-1959). “Life wasn’t worth a cigarette butt,” my father recalls.

But the new politicals were different. Many were hardened fighters and underground organizers who started “eye-for-an-eye” warfare with the criminals. The jailors noticed. If the politicals could fight the criminals, they could fight the authorities, too.

In the beginning of 1949, they separated the two groups and sent the “most dangerous” politicals, including my father, to special camps with the harshest conditions. A grueling, several-week train journey took him south to the sprawling Ozerlag prison complex in central Siberia.

That May, in Camp 26 near Taishet, my father and three other OUN-UPA veterans secretly formed one of the first cells of what would become known as “Polar OUN” or “OUN North” – the Ukrainian-led self-help organization in the camps. After reciting the OUN pledge – “Achieve a Ukrainian state or die in the fight for it” – they sealed their oaths with blood.

He remembers two of their surnames: Svyshch and Terpelyvets. When Svyshch decided to escape, the rest helped him plan it. In July, during the daily delivery of the detested balanda, Svyshch and three new recruits lured the guards away to seize their weapons and take them prisoner. For two days, they fled through the forests towards the west.

After releasing the guards, they should have separated so that one might make it back to Ukraine. But they didn’t and camp security captured them within days. They executed the two men and laid their bodies by the main gate as a warning. The escape’s failure meant that the OUN cell in Ozerlag’s Camp 26 had no hope of outside help — outside the gulag, that is. Inside, they found fertile ground for organizing. Using prisoner transfers, truck drivers and chance encounters, they made contact with compatriots in other camps. By 1950, OUN cells appeared all over Ozerlag and they changed their slogan to “freedom for all nations” to attract other ethnic groups.

That spring, my father transferred east to the notorious Vanino Bay on the Pacific. From there, Stalin’s slave ships shuttled tens of thousands of prisoners through a treacherous strait near Japan and on to the Kolyma region in Russia’s sub-Arctic northeast. Like Auschwitz in the Nazi concentration camps, Kolyma meant certain death in the Gulag.

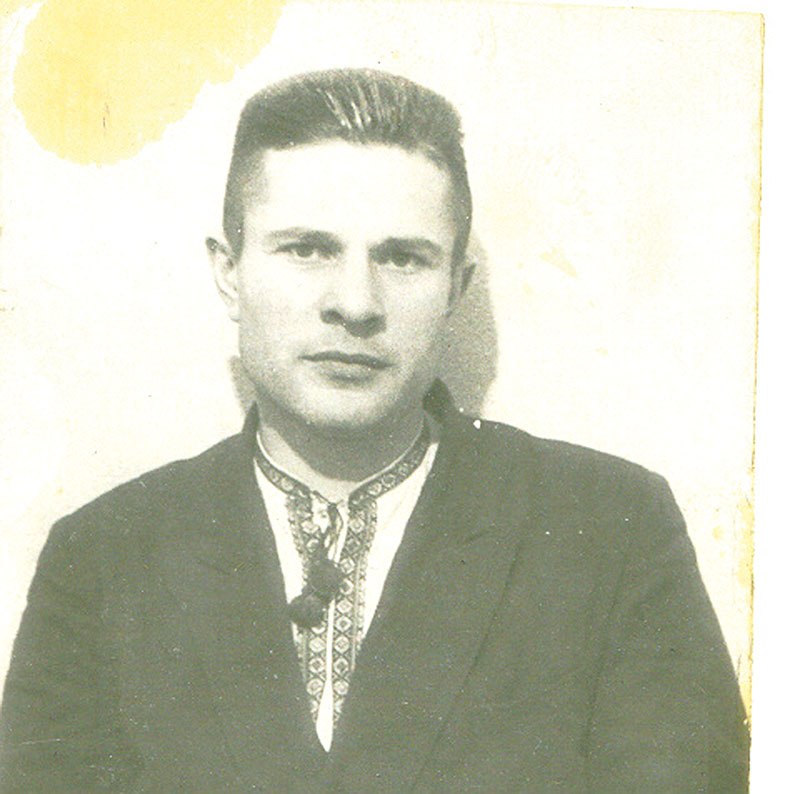

This photo of Myron Mycio was taken secretly in 1954 in Camp D-2 after Josef Stalin’s death, when prisoners were allowed to receive packages. His family found out he was alive and his sister sent him the embroidered shirt. In 1948, Mycio was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor for “counterrevolutionary activity” — being part of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. He served nearly nine years in various prison camps.

In a daring attempt to avert it, four Ukrainians including my father and Terpelyvets, a Belarussian Jew named Lyova, a Russian major called Biletsky, and Shablevsky, a Polish naval officer; secretly hatched a plot. When their turn came for the Kolyma voyage, they would capture their ship – the infamous Dzhurma – and steer it to the nearest Japanese island. To prepare, they planted their people among the ships’ civilian workers and the prisoners: my father headed the carpenters’ brigade. In the first days of July, when the Nogin set out with 2,000 prisoners, they sent agents to collect information.

Their conclusion: “Don’t do it.”

Two guard boats – a rarity – had escorted the Nogin for the entire journey. No one knew why, though it could have been because German POW convicts had seized their ship and set course for the United States a few months earlier. They were captured and shot but the incident might have tightened security.

Guard boats also accompanied the Dzhurma when it carried the Vanino Bay co-conspirators to Kolyma later that month. My father would spend the next five years in D-2, a secret camp on the Myaundzha River, where winters froze to -40 degrees and giant mosquitoes tormented the prisoners in summer.

But with Polar OUN’s help, he survived and helped others to, as well, delivering food and clothing to prisoners held in punishment cells.

After Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953, prisoner uprisings rocked the camps in Norilsk, Vorkuta and Kengir. In D-2, OUN launched its own war against the cruelest jailors and informants. “Terror was met with terror,” my father says, without many details except that Lyova killed one of the stoolies. The authorities lost more control with every day.

Revolting prisoners made the gulag untenable. The jailors needed too much security to keep it from exploding, raising alarms in Moscow. So, they let the prisoners go. In December 1956, having served nearly nine years of his sentence, my father got on a train to go home, never to eat fish again if he could help it.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote with grudging respect for the Ukrainians in the third volume of The Gulag Archipelago. His observations about the pre-war political prisoners’ reaction to them particularly resonate today.

The “orthodox Soviet citizens,” as he called them, condemned the Ukrainian-led war on informants and their fight for prisoners’ rights. “They accepted all forms of repression and extermination if they came from above – as manifestations of the dictatorship of the proletariat. But they saw the same kind of actions from below as banditry and, what’s more, the loyalists considered its ‘Banderite’ form to be bourgeois nationalism.”

It sounds, sadly, familiar. Today, Russians – most of them really neo-Soviet – are again calling Ukrainians who refuse to bow to dictatorship “Banderites.” But it is a badge of honor. From the EuroMaidan protesters to the soldiers on the front: all are demonstrating the courage and spirit displayed during the audacious Vanino Bay ship plot, when people like my father refused to submit meekly to a dictator’s monstrous penal machinery and, eventually, helped to bring the system down.

I am grateful that he has lived to see another generation take up that banner.

Mary Mycio is a lawyer and writer. Her most recent book is Doing Bizness: A Nuclear Thriller about Ukraine’s disarmament in the early 1990s.