Statistically, every fourth man and every sixth woman in Ukraine will be diagnosed with cancer. Of those cases, over 30 percent will be caught only in their final stages, according to Olena Kolesnik, director of the Ukrainian National Cancer Institute.

Ukraine’s incidence of cancer is not that far off its European neighbors’. But its situation diverges sharply and tragically when it comes to screening and treating the disease.

In few places is this more clear than in the difficulty sick Ukrainians have in getting care in the final stages of their lives.

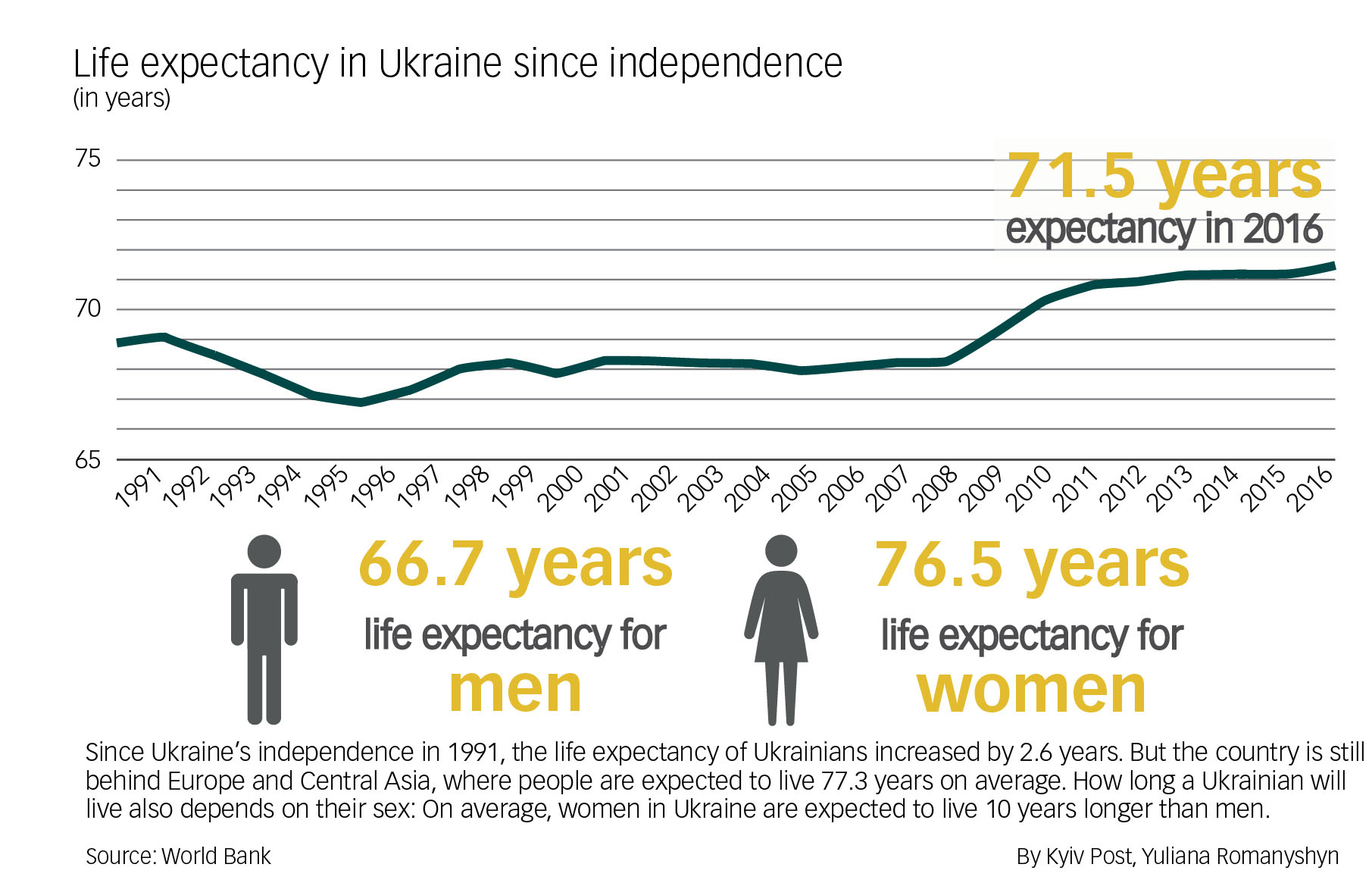

Life expectancy in Ukraine since independence

Few, shabby beds

The European norm for hospice centers is one bed for every 10,000 people, says Oleksyy Kalachov, the head of the department of palliative medicine in Kyiv’s city cancer hospital.

In Kyiv, a city of three million people, the number is half what it should be, he says: 135 beds. They’re spread through three city-owned hospices, and one palliative care center. Two of the hospices are in bad condition.

Oleksandr Wolf, head of the Association for Palliative and Hospice care in Ukraine, said that Kyiv’s Hospital 10 hospices, for example, have bad conditions and mostly takes care of homeless people.

But a bigger problem, he said, is that medical practitioners in Ukraine don’t have much of a concept of what hospice care should be.

“Palliative and hospice care are not just diapers, but a technology where communication is valuable. This includes bereavement care. In Ukraine, there are no such technologies,” he said.

One issue is the number of caregivers. In Ukraine’s hospices, there are 10 to 15 patients per one medical worker, while across the border, there are only two to four. This means far less attention to the dying.

Wolf said the problem is wider, across Ukraine’s medical system. “Our political elite, who come up with laws, live in a different dimension then everyone else in Ukraine,” he said.

In Kyiv, there is only one hospice with proper conditions, said Wolf — the one where Kalachov works. Part of the Kyiv Oncology Center, it is well-equipped and has highly trained specialists to provide care for people, specifically during their last stages of life.

“Mortality in our hospice is 87 percent during the three months of patients being here,” said Kalachov.

Low quality of death

If Kyiv’s hospice is patchy, the situation across the rest of Ukraine is arguably worse. On The Economist’s latest 2015 Quality of Death Index, Ukraine ranks between Ethiopia and Colombia, at 69th place out of 80.

In a country with 42 million people, there are eight hospices and 57 care units. Approximately 70 percent of their patients are people with last stages of cancer, said Wolf.

Ukrainians who live in such regions as Kyiv, Zaporizhzhia, Sumy, Kirovograd or Odesa have the highest chances of being diagnosed with cancer. The most complicated cases are directed to the Kyiv Institute of Cancer, which provides more qualified assistance than in any other hospital across the country.

But, in the end, very few Ukrainian patients can either find or afford palliative care. Only 15 percent of patients receive proper end-of-life treatment, according to the non-government organization, “Ukrainian league for the development of palliative and hospice assistance.”

For those who don’t want a public bed, there are alternatives: private palliative care centers or nursing services. However, at $15 to $30 a day, they are often out of reach for the average Ukrainian.

Oleksyy Kalachov, head of the department of palliative medicine in Kyiv city cancer hospital stands in church in hospice on May 3. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Will reforms help?

Ukraine’s hospice situation is changing. Ongoing medical reforms mean that more hospice centers are under construction, says Kalachov. But Wolf said the improvements, so far, have been superficial at best.

He describes hospitals in small towns being renamed “hospice centers,”—but without bringing in expertise, or instructing medical staff how to care for the dying.

“There’s a lack of support and the proper level of communication,” he said.

Kolesnik, the director of the Ukrainian National Cancer Institute, says that cancer treatment in general in Ukraine remain underfunded.

“We still have a big gap between what the hospital needs and what the state can allocate,” Kolesnik said.

“This year we received around $7 million, which is 11 times less than what we need to cover all our needs.”

In 2018, these allocated funds will be enough to meet only 30 percent of patients’ needs for medical supplies and 50 percent of medications, including chemotherapy, Kolesnik said.

But investing into the health of Ukrainians could pay off in the long run. Cancer in Ukraine’s working age population means that Ukraine’s gross domestic product is losing $180 million per year, says Kolesnik.