The government focused on fighting the pandemic this year, further stalling reform in the energy sector as the state amassed a $1 billion debt to green energy developers.

But important steps did take place: Ukraine opened its gas and its electricity markets for competition.

Green investors deterred

The green-tariffs crisis in renewable energy has been the most talked-about event, with Ukraine’s government reneging on guarantees in pricing made to lure investors.

Today, renewable energy secures about 8% of all the energy produced in the country, while the government’s official goal is 25% by 2035.

Ukraine started to foster green energy production in 2008, when it introduced green tariffs, obliging the company known as State Guaranteed Buyer to buy renewable electricity at the highest price in Europe — 0.46 euros per kilowatt.

The tariff has been lowered since then to roughly 0.13 euros per kilowatts, but it’s still one of the highest in Europe.

The strategy seemed to work: The number of investors in this sector increased significantly and renewable power generation climbed from 3.9% in 2014 to today’s 8%.

But when the pandemic hit, the state couldn’t keep up with payments anymore. Many green energy developers, deprived of fast returns, were left with debts. After much negotiation, the government and investors reached a compromise to repay the government debt in exchange for reducing the tariffs.

But Ukraine still hasn’t managed to pay off the debts and several renewable developers have threatened the state with international arbitration.

Ukraine’s government now plans to eventually get rid of the controversial green tariff and introduce competitive auctions for green producers to sell their electricity to other buyers.

The auction system promises to reduce electricity costs for consumers and introduce Ukraine to European standards in energy.

Under the new system, Ukrainians will be able to freely switch suppliers and benefit from pricing that is market-based and not set arbitrarily by the government.

In 2020, however, not a single new investor put money in renewables.

All that said, Oleksandr Kharchenko, managing director at the Energy Industry Research Center, thinks the green industry crisis won’t have a huge impact on the energy industry.

“It needs to be managed,” he said, “but it serves only as an example of stupidity and corruption” of Ukraine’s officials.

Green energy production is still too small a share of all electricity generated in the country.

Opening electricity market

One victory is the liberation of the electricity market.

For years since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the state dictated the prices to private electricity firms. Starting this year, however, energy firms can set their own prices.

Next year, energy officials also plan to reduce the public service obligation, which forces energy producers to sell some of their power to the state at below-cost prices to keep energy cheap for the public.

Nuclear power producer Energoatom, for example, today has to sell 80% of its electricity to the state cheaply. The change may help companies like Energoatom to generate more profit and improve their service.

Gas market liberalization

The year 2020 has also freed up the local gas market.

The government opened the gas market in August, canceling public service obligations too. Now consumers can freely change suppliers.

In the past, they had to pay the prices set by the government and use the services of specific gas providers, 75% of which belonged to exiled oligarch Dmytro Firtash, who is fighting U.S. corruption charges.

It also prevented state-owned gas company Naftogaz from selling gas directly to end-users. Gas companies have already announced their entry into the renewed gas market — from state-owned Naftogaz to smaller traders.

Acting energy minister

Yuri Vitrenko, former executive director of state-owned gas giant Naftogaz, was appointed acting energy minister on Dec. 21 by the Cabinet of Ministers, a week after the Verkhovna Rada voted against his appointment.

Vitrenko’s appointment in a sector dominated by oligarchs signals that President Volodymyr Zelensky and Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal are intent on attacking corruption in the energy sector, despite parliament’s efforts to block reforms.

During his time at the head of Naftogaz, Vitrenko spearheaded successful litigation against Russia’s state-controlled Gazprom, leading to a $2.9 billion arbitration award in a dispute over fees for transiting Russian gas through Ukraine’s pipelines.

After he left Naftogaz in May amid a fallout with his former ally CEO Andriy Kobolyev, Vitrenko said in a Kyiv Post interview that billionaire oligarchs Ihor Kolomoisky and Firtash, still have too much power over the sector.

“The oligarchs never left,” he said.

Firtash controls 75% of Ukraine’s regional gas supply companies and owes Naftogaz more than $1 billion for unpaid natural gas supplies. Kolomoisky, likewise, long stands accused of milking Ukrnafta, the state oil producer, for huge profits and stiffing the public with a large unpaid tax bill, also measured at more than $1 billion.

At the time, Vitrenko also called for Naftogaz — with $10 billion in revenue and 80,000 employees — to be privatized or liquidated because it’s not being run as a modern company, noting that oil and gas production has been stagnant for decades.

An employee of state-run gas extracting giant UkrGasVydobuvannya operates at a gas drilling site in Poltava Oblast on Oct. 24, 2018. The year 2020 has freed up the local gas market: The government opened it in August, canceling Public Service Obligation (PSO) in the gas subsector. Now consumers can freely change suppliers, depending on their prices and services offered. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

Forecast for 2021

Largely, however, 2020 was a year of inaction and lack of decisions, according to energy expert Yuri Kubrushko.

Kubrushko said the important issue to watch in 2021 is whether the state can pay off its $1 billion debt to renewable energy producers and reduce the influence of oligarchs in the sector.

He also believes the government should increase electricity and gas prices for households — an unpopular but long-overdue move.

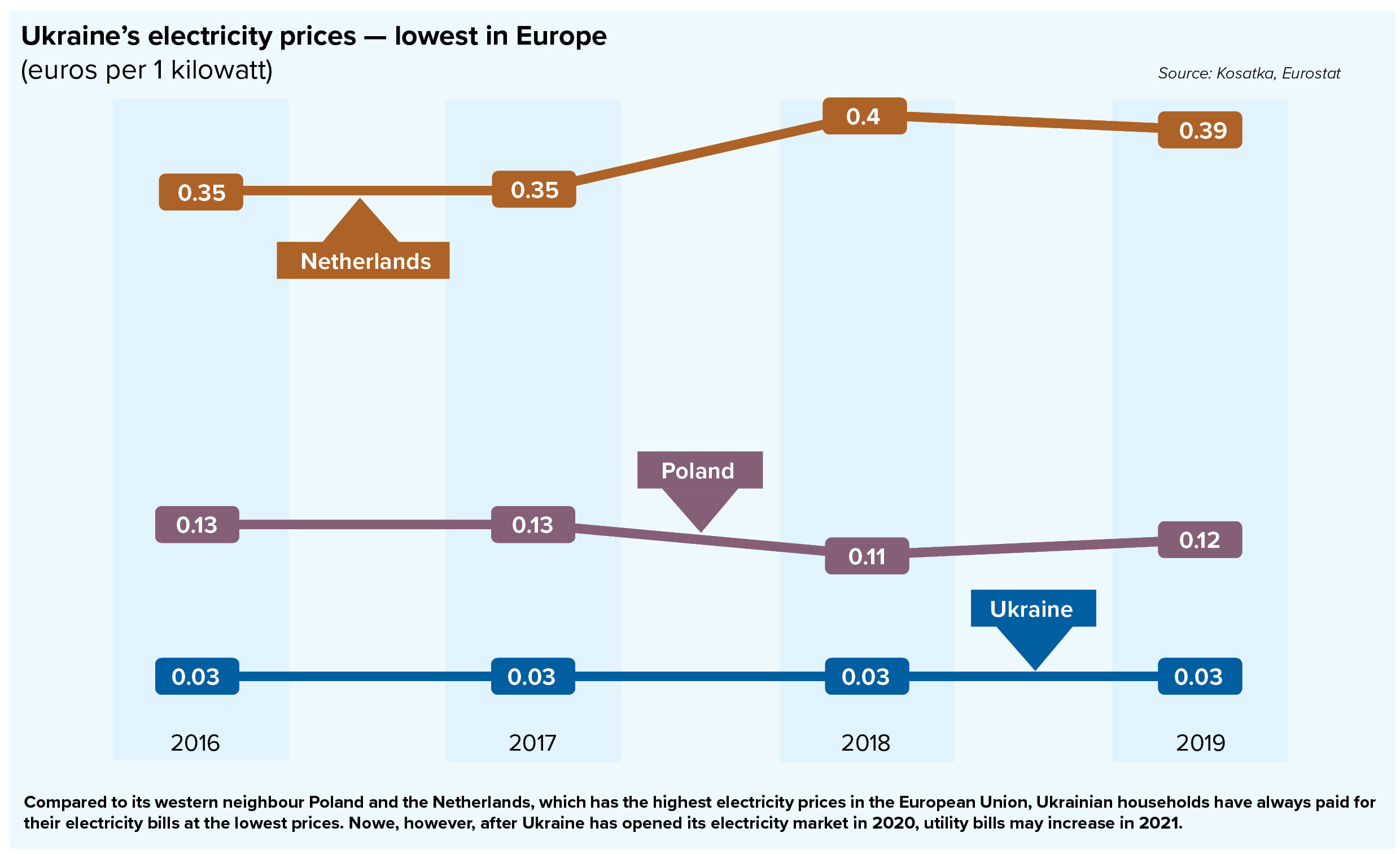

The current prices, which aren’t based on the market, are among the cheapest in Europe. As a result, energy producers and distributors can’t afford to invest properly.

Everything will depend on the government’s ability to show leadership and to appoint a good team to lead the energy sector, Kubrushko said. “Otherwise, it will be another wasted year which will kill the sector,” he said.