At least $11 billion in non-performing loans from deadbeat borrowers is still on the books of the country’s state banks, an amount that equals about 20% of the annual state budget.

The share of bad loans in the portfolios of these banks declined from 63.5% to 57.4% in 2020, but the struggle to shed them is far from over. The longer the banks take to sell their unneeded assets, the more their market value decreases, according to experts participating in a Kyiv Post webinar titled “Ukraine’s Mountain of Bad Debt: How to Collect?”

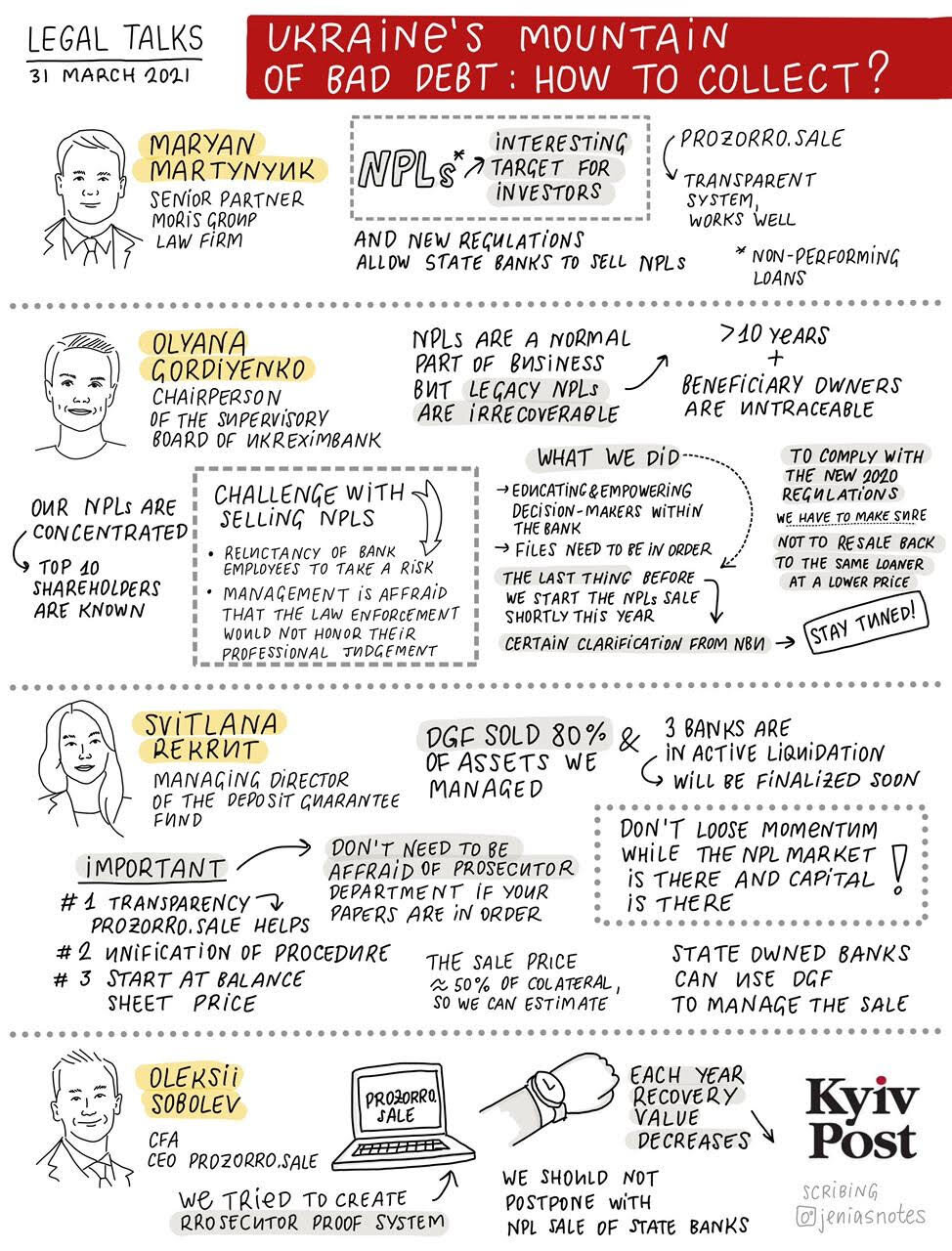

The event was sponsored by Moris Group law firm, whose senior partner, Maryan Martynyuk, said investors are very interested in acquiring these assets when they are up for sale. “It’s a huge market, actually,” he said. But he said that Ukraine’s state banks have yet to put their large portfolio of distressed assets on the market, keeping investors waiting for “the next wave of the non-performing loans” to hit the market.

Martynuk’s law firm successfully represented the winning bidder of Odesa’s Chornomorets Stadium for $7 million at a state auction lastyear after it was repossessed from its former owner, Leonid Klimov, whose Imexbank collapsed, costing taxpayers $165 million.

Oleksii Sobolev, CEO of ProZorro.Sale, oversees the online bidding platform on which many of these assets from private banks have been sold competitively and transparently. He said legal safeguards have been put in place in recent years to reduce shady transactions and attract a better price for assets on the market.

But he said that, the longer the delays in selling off non-performing assets, the lower their value — and hence the less that taxpayers will recoup from the banking sector collapse that cost taxpayers at least $20 billion in the last decade.

Svitlana Rekrut, managing director of the Deposit Guarantee Fund, agrees that banks should act while there’s still demand and while investors are ready to spend their money. The Deposit Guarantee Fund owned assets worth an estimated $20 billion in 2020 and 90% of them were bad loans. The fund has reduced that to $3 billion, according to Rekrut. “If you don’t provide a pipeline to the market, the capital will go,” Rekrut said. Once it’s gone, it will be harder to bring the interest back to the market of non-performing loans and money will flow elsewhere, she said.

The managing director is confident that, by the end of 2021, the market will “vanish” unless state-owned banks make a move. The Deposit Guarantee Fund has sold most of its bad debts. The priority was to sell them even if it meant to reduce the price significantly. The fund has recovered $1.4 billion, according to Rekrut, for taxpayers. “Till the end of the year, our assets from banks will be zero,” she promised.

Kyiv Post Legal Talks webinar, sponsored by the Moris Group, took place on March 31, 2021, on the subject of $15 billion in non-performing loans in Ukraine’s banking sector.

Cleaning up the mess

Before major banking reforms started in 2014, even the National Bank of Ukraine didn’t know the true beneficiaries of some of the banks — they weren’t required to disclose their identities. This created a situation in which owners lent to themselves, their businesses, their friends and allied lawmakers with little to no intention of repaying the loans. The mayhem of insider lending collapsed after Kremlin-backed President Viktor Yanukovych fled Ukraine, ousted by the EuroMaidan Revolution in 2014.

Private banks have done a better job of reducing their non-performing loans over the past several years, mainly by writing off bad debts that are more than 90 days past their due date.

Today, private banks have $4 billion worth of non-performing loans. State-owned banks have a bigger hole to fill.

To tackle the mountain of debt, the goal in the government’s recent reform strategy is to have reduced the share of such loans to below 20% by 2025.

Fear of prosecution

Olyana Gordiyenko, the chairperson of the board of directors of state-owned Ukreximbank, says banks have been reluctant to take a proactive approach in reducing non-performing loans because of the risks associated with them. Assessing the assets’ value is difficult, and prosecutors will question the reasons and sale price of distressed assets. “You cannot answer them (by) saying, ‘I’m a banker, I have a professional discretion and you need to trust me,’” Gordiyenko said.

Before the government began allowing state-owned banks to sell such loans with discounts last year, there was a fear that bankers could face criminal charges for mismanagement of state funds. With legal changes in place to protect against such circumstances, the next step is to start selling these distressed assets more actively.

Jenia Poluektova-Dehghani created the sketch of the Kyiv Post Legal Talks. The drawing was commissioned by Olyana Gordiyenko, chair of the supervisory board of state-owned Ukreximbank.

Worthless debts

Some non-performing loans in Ukreximbank’s portfolio are more than 10 years old. Their ultimate beneficiaries are unknown and hence they are “totally irrecoverable,” Gordiyenko said.

Rekrut said the sales can be discounted heavily. Non-performing loans that have existed for more than 10 years, in turn, are almost worthless because of the difficulty of collecting or identifying the beneficiary owner.

On average, Rekrut says, the Deposit Guarantee Fund recovers around 7%. The ratio depends on the type of asset and its quality. For example, it can be over 100% when this is real estate. But if the asset is not valuable, it can be below 1%.

Sobolev says that the recovery value “decreases drastically” every year. The value can drop by 10 times after the first five years and by 100 times after 10 years.

He insists that the process should begin now before their value decreases further.

Martynyuk also emphasizes that it is “crucial” for state-owned banks to indicate that they are ready to sell non-performing loans to everyone and that they want to get rid of them as fast as possible.

Gordiyenko says that all regulations are “in place” for Ukreximbank to start selling bad debt, which is “huge in our bank” and which is freezing up credit because of the currency reserve requirements put in place to ensure that the debts can be written off if needed. The state-owned bank needs to lend, but cannot do so until the non-performing loans are reduced, she explained.

“If we are not lending, the bank shrinks and we will need to give up our license to the national bank and merge with the Deposit Guarantee Fund,” Gordiyenko said.

Main Points

- Until recent changes in the law, the fear of criminal prosecution was discouraging state-owned banks from selling non-performing loans more proactively at current market prices.

- When selling NPLs to investors, transparency and having one simplified set of procedures for the banks to follow will help avoid criminal investigations. All files need to be prepared to show the reasons for the sale and how the selling price was decided.

- NPL borrowers are taking advantage of the fact that state-owned banks are slow to liquidate assets.

- There are still investors interested in buying NPLs, but the market will vanish unless the state-owned banks start selling them to meet the demand. The longer that the state-owned banks hold on to these assets, the further their value decreases.

- Though the state-owned banks should speed up their disposal of distressed assets, they should also be careful that the buyer of the NPL is not a third party acting as the borrower’s agent, which is very difficult to control.

Key quotes

Maryan Martynyuk

“Everyone is expecting the state-owned banks to create the next wave of non-performing loans on the market.”

Olyana Gordiyenko

“Bankers need to make sure that the level of non-performing loans does not exceed the target and they all know the targets.”

Oleksii Sobolev

“With each year, the recovery value (of the distressed loan) decreases drastically.”

Svitlana Rekrut

“Don’t lose the momentum, the non-performing loan market exists right now, there is capital there. (But) if you don’t provide the pipeline to the market, the capital will go.”

Read some of the Kyiv Post’s best coverage of the banking sector for more information:

Unpunished Bank Fraud – Feb. 14, 2020

Banker Busts – Nov. 22, 2019

Legal Quarterly – Oct. 5, 2018

Unpunished Bank Fraud – June 8, 2017

Legal Quarterly – Dec. 23, 2016

Legal Quarterly – July 1, 2016

Ukraine’s Epic Banking Disaster – July 1, 2016