The Netherlands is 14 times smaller than Ukraine, but its trade turnover is 12 times larger.

In 2019, the Netherlands was the world’s eighth largest exporter of goods, selling commodities worth $710 billion abroad. The Dutch are among Ukraine’s main trade partners in the European Union — last year, the turnover between the countries amounted for $2.6 billion. That trade volume has been increasing for four years running.

This year, however, the upward trend might be at serious risk. The COVID‑19 pandemic is harming trade around the world. Ukrainian agriculture — which accounts for 80% of bilateral trade — remains under-performing.

Trade priorities

When many people think of the Netherlands, they imagine flowers. The tulip is one of the country’s symbols, and flowers are a major source of revenue for the Dutch.

Ukraine alone imported $21 million worth of Dutch roses, chrysanthemums, carnations and other flowers last year, a 20% jump compared to 2018.

But as the world struggles to curb the spread of COVID‑19, the global floral market is withering.

Trade priorities are changing rapidly.

“It’s a disaster,” said Reinoud Nuijten, agricultural counselor at the Embassy of the Netherlands in Ukraine. “As members of the embassy, we were preparing to have a Dutch pavilion at a flower expo in April, but we had to cancel it, as well as a visit of a large delegation of Dutch companies.”

Apart from flowers, Ukraine imports pharmaceuticals, tobacco, cars, chocolate and milk products from the Netherlands — $907 million worth of Dutch goods in 2019. But import figures appear modest compared with Ukraine’s exports to the country, worth $1.9 billion in 2019.

The Netherlands is one of the top five destinations for Ukrainian agricultural products, along with China and India. Ukraine’s grains, seeds, sunflower oil, vegetables and poultry accounted for 80% of its total exports to the country of tulip fields and windmills.

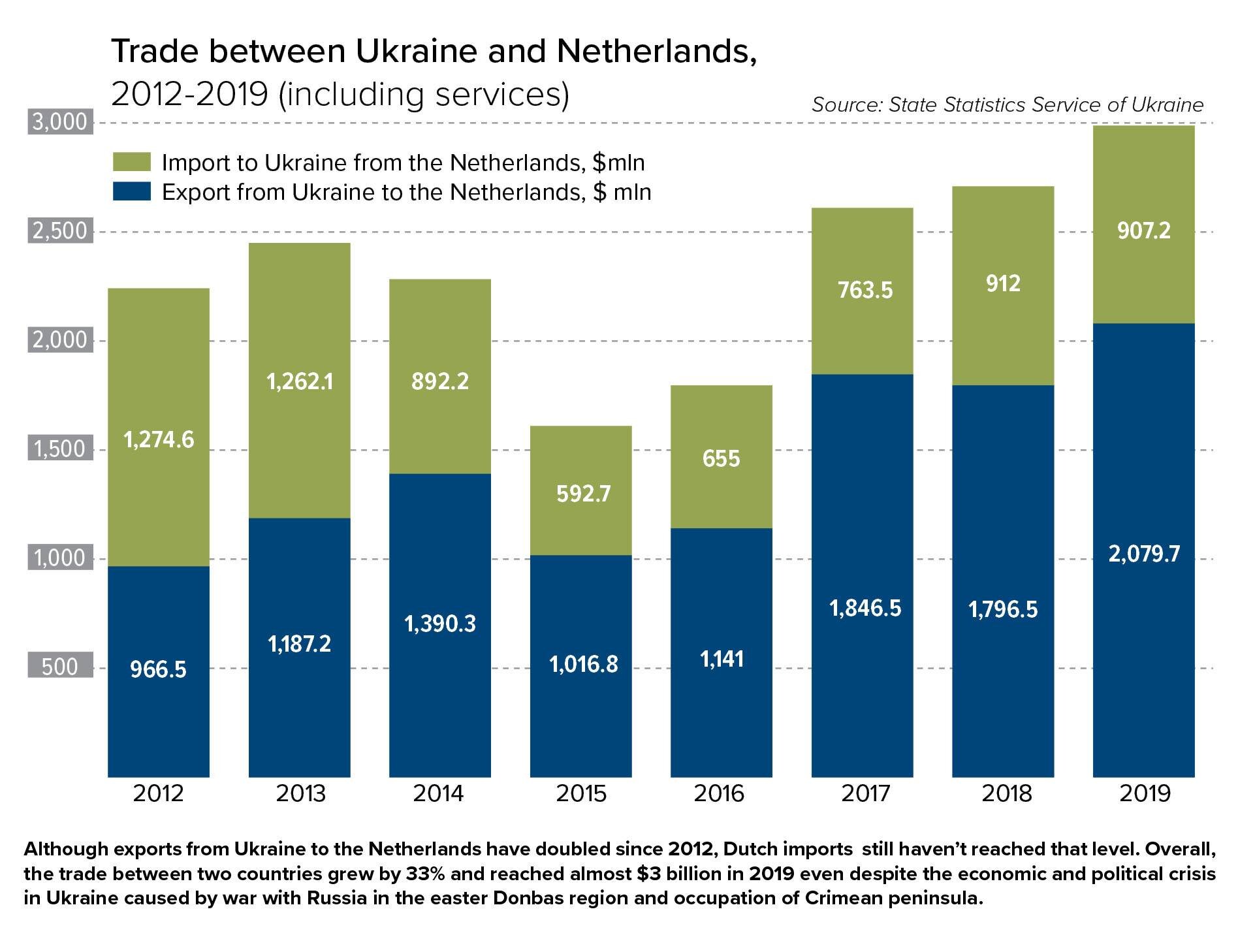

Overall, trade between the countries — including services — reached $2.9 billion last year, $400 million more than in 2018. It was a record turnover for the last seven years of Ukrainian-Dutch trade relations.

This year, Ukrainian agribusiness even has a chance to contribute to Dutch food security more than other countries during the pandemic since Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers, unlike some other governments, hasn’t banned agricultural trade.

This year, Ukrainian agribusiness even has a chance to contribute to Dutch food security more than other countries during the pandemic since Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers, unlike some other governments, hasn’t banned agricultural trade.

“If you talk about international solidarity, I can say a number of countries are doing the opposite,” said Nuijten from the Dutch embassy.

That decision will also guarantee the inflow of foreign currency to Ukraine, the poorest country in Europe, which can help it stay afloat during a global economic recession. Last year, trade brought Ukraine $9.6 billion, or 40% of all foreign cash flow.

But to continue beneficial trade, including with the Netherlands, and to minimize risks, Dutch agriculture experts urge Ukraine’s farmers to stop mindlessly squeezing all they can out of the country’s fertile soils, causing soil depletion and potentially damaging Ukrainian agriculture in the long run.

Instead, Dutch businesspeople working in agriculture say Ukraine should start investing heavily into the dairy industry, which they see as one of the most profitable niches.

Lack of standards

While Ukraine is breaking its grain harvest records every year, domestic dairy production is stagnating. It constantly fails to reach the high standards, professionalism and the “long-term” think of the dairy industry in the Netherlands, Dutch experts say.

Instead of producing more milk and value-added milk products like butter and cheese, Ukraine has chosen to import them, including from the Netherlands.

“Ukraine has to reorganize all production around cow keeping, increase the scale of farms, change the quality of infrastructure,” said Nuijten. “That’s not done overnight.”

If done right, the export of milk products like milk powder, baby food or cheese can bring Ukraine huge profits. But from year to year, the number of cattle in Ukraine is only decreasing. Since 1991, the number has dropped from 24.6 million cows to just 3.3 million.

“If you are doing it professionally, you can make nice money on cows,” said Rene Kremers, managing director at DIFCO International, a Dutch company specializing in dairy production projects.

Over the past seven years of hard work in Ukraine, Kremers has trained over 1,000 cow specialists. They’ve installed individual milk control in a Lviv laboratory, where each cow can be tested. And they supplied testing facilities to detect zoonotic diseases in Kyiv veterinary centers. Kremers clearly sees what is wrong with the Ukrainian dairy industry: the quality of milk, which nobody is really monitoring.

Kremers points to the Dutch success in this area: China is buying all baby formula powder from the Netherlands, which they trust because the milk is tested “for everything.”

“Sometimes (such sanitary control) is really annoying for the farmers, but if something is wrong, we are immediately reporting about a problem,” he said. “And this is what China wants. For milk with problems — they can produce (it) themselves.”

In Ukraine, production could be much cheaper due to favorable conditions and the amount of available space.

Still, the Netherlands has certain advantages. Dutch farmers are more open. It is common for them to share their knowledge with each other, even their budget figures to compare costs and prices.

“They are doing it to learn from each other,” said Kremers. “In Ukraine, it is a completely different situation.”

Additionally, Ukraine suffers from agricultural education that is too theoretical, something very different from what happens in the Netherlands. “They learn complete books, but they’ve never seen a cow,” Kremers said.

Not so fertile anymore

Ukraine has long been famous for its rich soil and was known as the breadbasket of Europe. But that may soon be history.

“The soil quality in Ukraine is decreasing very fast,” said Nuijten from the Dutch embassy. “It sounds like (it’s) far away, but in case farmers don’t pay attention now, it will only be a few decades away from the point when it’s a problem for the whole country.”

As an agrarian expert, he sees that in southern Ukrainian oblasts — Mykolaiv, Odesa, and Kherson — the black soil has really shrunk. It forces farmers to move to the north, where the soil is better.

“Take climate and sustainability very seriously,” said Nuijten, drawing parallels with the Netherlands, where ecology is strictly regulated by the law. “You cannot afford all the losses of nature and biodiversity because you cannot recover from that very easily.”

Ukraine needs better crop rotation, improved irrigation and to use enough fertilizers to help the soil’s recovery. On average, one hectare has 3,000 kilograms of organic compounds, but if that amount is gone, “your soil doesn’t work anymore,” the expert says.

In the long term, it can undermine the agrarian industry in Ukraine and decrease its international trade, including with the Netherlands. “So you have to make sure that soil stays alive,” said Nuijten.