Hakan Yazici is just one of numerous businesspeople working in central Kyiv. He runs a print and copy shop popular with students of Taras Shevchenko National University, and also operates a small online store on Amazon.com, designing and selling drink coasters in the United States.

But Yazici differs from most of the entrepreneurs around him in one way: he is a Turkish citizen living in Ukraine on a temporary residency permit. And that makes certain aspects of his work a challenge.

Yazici has discovered that, in practice, he cannot easily deposit money on his Ukrainian bank account. He has also had problems transferring funds — even amounts that, globally, are quite small.

That predicament is not unique: Many foreign temporary residents in Ukraine have struggled with the country’s byzantine currency and banking rules.

But a new currency law that entered into force in July has some hoping the situation may improve. It’s still in a transitional period and has not been entirely implemented, but some banking analysts suggest the law looks better on paper than it actually is.

Foreign exchange

Yazici has lived in Ukraine for five years. He has a wife and a child — they are his legal ground for residency. He is also registered as a “physical individual-entrepreneur,” more frequently abbreviated in Ukrainian as FOP. Despite bureaucratic difficulties and the high interest rates on loans, Yazici has managed to open a successful business.

But as a temporary resident, he cannot deposit profits in his bank account — unless he can prove where they came from. That poses a challenge for a man whose shop often carries out relatively small typography jobs frequently paid for in cash.

“There’s a conflict between the government giving you the right to have a company (and not giving) you the chance to take (payment) in cash or put cash in your bank account,” Yazici says.

Most surprisingly, currency controls have also affected Yazici’s Amazon store. Recently, he wanted to send money to a Chinese manufacturer to produce a batch of coasters.

However, the central bank would not allow the transfer, suggesting that Yazici was an importer and thus needed a special license — even though the product would never reach Ukrainian shores.

Ultimately, Yazici found a workaround. He gave the money to his wife and she deposited it in her PrivatBank account (as a Ukrainian citizen, she could do that). Then, using PrivatBank’s money transfer application, she sent the money to Yazici’s Turkish bank account. From there, it took only a few minutes for him to convert the money to dollars and send it to China using a standard SWIFT transfer. A few days later, his manufacturer had the money and could start making the coasters.

All’s well that ends well, but this isn’t good for Ukraine, Yazici believes. In SWIFT transfers, the banks involved often make money off currency conversions and levy fees on the transaction. But if that transfer never touches Ukraine, the Ukrainian economy is losing money.

“Now the Turkish bank gets money from SWIFT,” Yazici says.

The Nigerian way

Yazici is not the only one adapting to currency operation problems. Nigerian Michael Akwara has also seen and experienced the challenges people from his country — who often come to Ukraine to attend medical school — face financially.

He arrived in Ukraine to study electrical engineering at Luhansk State University in 2012. Less than two years later, he found himself in the midst of a war zone when Russia invaded the Donbas.

After many sleepless nights filled with the sounds of gunfire and explosions, Akwara fled to Vinnytsia, and then to Ternopil, where he continued his education. After graduating, he moved to Kyiv to pursue a master’s degree in innovation.

Now, he is involved in an innovative project: helping Nigerians in Ukraine bypass the country’s onerous currency controls.

Most Nigerian students face significant challenges in Ukraine. Receiving a visa to come and study in the country is not easy, something Akwara attributes to corruption.

“You definitely need to get somebody inside before you will be issued a visa. If you don’t have an insider, forget it,” he says. “And having an insider entails money — sometimes $3,000 to $4,000 just to get a visa.”

Once inside Ukraine, students often struggle to cover tuition, and failing to pay on time can result in expulsion. If the student does not re-enroll in the next seven days, he or she is residing in Ukraine illegally. Akwara estimates that 40 percent of Nigerian students are no longer legally registered.

There are also many Nigerians working in Ukraine, both legally and off-the-books. They have achieved significant success in importing Nigerian foods to Ukraine to cater to the needs of the over 10,000 of their compatriots living in the country, Akwara says. And they often want to send money home to support their families.

For all these reasons, moving money to and from Ukraine and avoiding high ATM withdrawal fees is of paramount importance to local Nigerians.

Akwara believes he is part of the solution. He is a manager at Keycom Online Solutions, an e-commerce company that helps Nigerians transfer money more efficiently, and has also branched out into bitcoin and providing invitation letters to Ukraine.

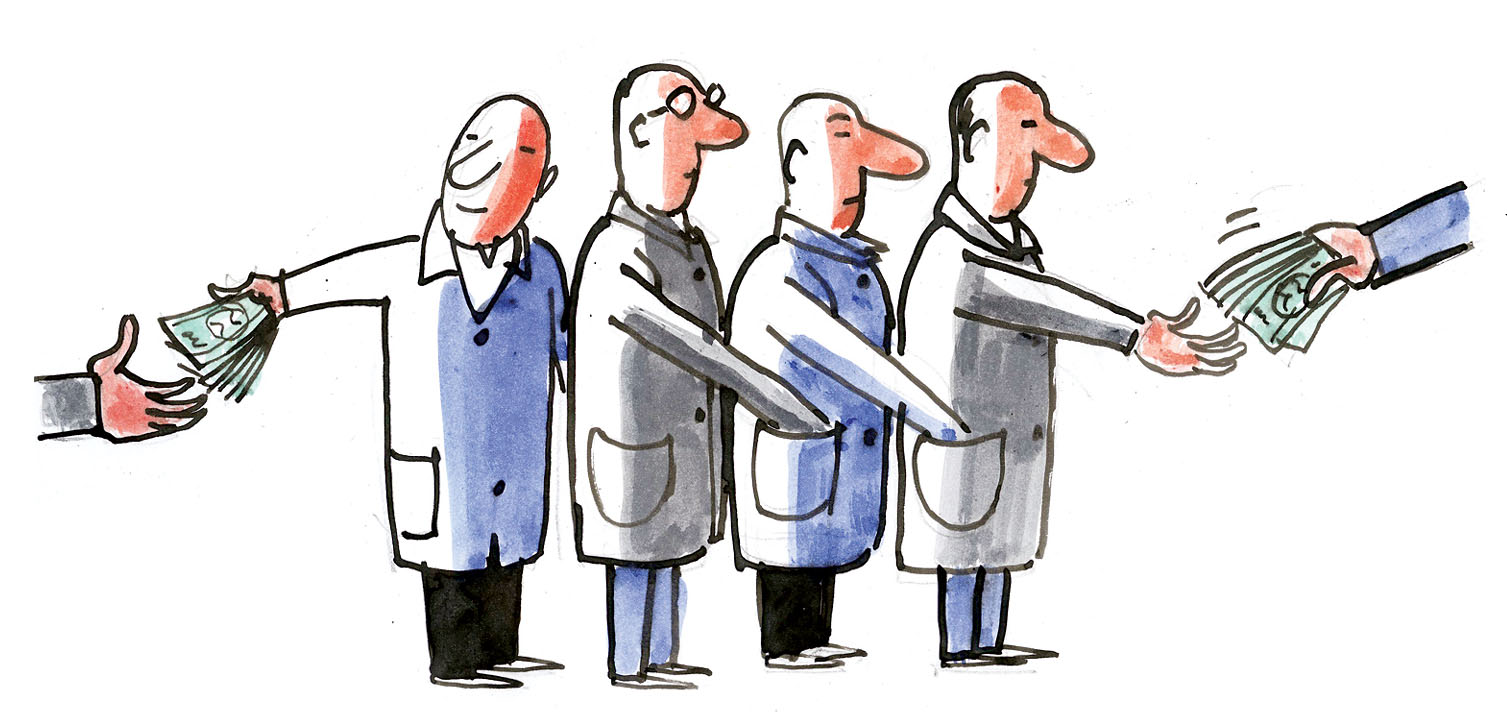

The technique is simple. The company has bank accounts in both Nigeria and Ukraine. A Nigerian in Ukraine can transfer money from a personal Nigerian bank account into the company’s Nigerian account. Then, he or she will receive that money in Ukrainian hryvnia or dollars (calculated according to the black market exchange rate) from the company’s bank account in Ukraine.

The money never actually crosses a border, allowing the sender and the receiver to avoid the difficulties and costs of regular money transfers.

“We have a website, everything is very transparent,” Akwara says. “If we’re dealing with Nigerians, we have to be transparent. If you’re not transparent, they’ll probably think you’re fraudulent.”

Change?

While Akwara appears to have found a solution to Nigerians’ currency woes in Ukraine, Yazici is hoping for more mundane help: the country’s new currency law.

Signed by President Petro Poroshenko in July, the law is part of Ukraine’s association agreement with the European Union. It aims to liberalize currency transactions, attract investors to the country, and make it easier for Ukrainians to invest abroad.

One particular provision is of interest to Yazici: foreign economic transactions that do not exceed Hr 150,000 — or roughly $5,340 — will no longer be subject to currency controls. The funds that Yazici struggled to send to China were definitely below that limit.

But while that sounds good, the currency law may not be as straightforward as he thinks.

Ukraine’s old currency law, which dates back to 1993, is of a restrictive nature: everything that isn’t expressly legal is prohibited.

“The new law will provide for new principles: everything that is not forbidden is allowed,” says Viktoria Sydorenko, a manager in Deloitte’s taxes and legal department. “It’s more freedom in currency control.”

The old law was an “outdated document” defined by bureaucratic logic, while the new one works on market principles, she says. Additionally, the old law — initially intended as a temporary measure — was created to prevent the transfer of vast amounts of capital from Ukraine. It does not take into account the many ways the economy has changed since 1993.

But while Sydorenko believes the law is an important positive step, she says it is difficult to predict how exactly it will affect temporary residents like Yazici and Akwara.

According to her, temporary residents already have legal grounds to transfer their earnings abroad. But judging by Yazici’s experience, actually being able to do that is another thing entirely.

Moreover, before the new law goes into effect in February, the National Bank of Ukraine has the right to impose certain restrictions, limitations, and clarifying rules to govern currency operations. What this will look like remains unclear.

And while the law will eliminate currency control for small operations, there will still be currency oversight.

“We will have to see how the banks will treat these different definitions,” Sydorenko says.

There is another criticism of the law, according to Oleksandr Savchenko, president of the International Institute of Business in Kyiv and a former deputy finance minister and deputy central bank governor.

The new law does not place enough limits on what the central bank can do to restrict currency flows. The ability to remove capital should be “ironclad,” Savchenko believes.

“We have the harshest limits on removing capital and the largest outflow of money during economic crises,” he says. This shows that strict regulations “don’t work.”

But with few other solutions on the horizon, Yazici hopes that the new currency law will at least make it easier for him to send money to his coaster manufacturer. He says he loves Ukraine, but finds this currency issue particularly frustrating.

Meanwhile, Akwara isn’t holding out hope. He feels that the $5,340 limit on currency control-free operations is too low. He believes this will make life more difficult for successful business people.

Akwara suggests a distinctly libertarian alternative: “There shouldn’t be a restriction on the amount.”