By Ukrainian standards, ArcelorMittal looks like a model of corporate social responsibility.

On its website, the Luxembourgish multinational steel manufacturer features a touching video of employees from its many branches discussing the importance of on-the-job safety.

ArcelorMittal publishes quarterly sustainability reviews, and also larger country-focused reports. And it claims to orient its work around “10 sustainable development outcomes,” ranging from carbon and energy to people.

But in March, after the roof at a converter shop at ArcelorMittal’s Kriviy Rih factory collapsed, killing one worker, some of the company’s Ukrainian employees rallied to demand wages of 1,000 euros a month and safer working conditions.

As negotiations with management waxed and waned, the workers held several other protests, at one point paralyzing production for three days in May.

Labor disputes can erupt at any company. But the case of ArcelorMittal — a multinational that touts its reputation for sustainability — raises a larger question: Can for-profit companies truly demonstrate much heralded “social responsibility,” particularly in a less regulated, developing economy like Ukraine?

Vague concept

Corporate social responsibility — often abbreviated as CSR — is one of the buzzwords of 21st century business. And it is increasingly finding a home in Ukrainian companies.

But for all its growing importance, CSR is a slippery concept. Even experts struggle to offer up a broadly accepted definition.

Maryna Saprykina, the CEO of Kyiv’s Corporate Social Responsibility Development Center, stresses that CSR focuses on decreasing a company’s negative impact on society and increasing its benefits for its local community.

Unlike charitable giving, which simply hands money or resources over to a good cause, CSR focuses on the sector in which the company works, involves company employees, and is connected to the long-term business goals of the company.

Saprykina provides the example of a car company. If that company buys food for needy people, that’s charity. But if the company harnesses its resources and employee to launch a campaign that aims to prevent auto accidents, now the company is working in CSR.

“The key thing is when companies understand their influence,” she says.

Nike scandal

CSR professionals stress that responsible business is not simply a public relations strategy. However, historically, efforts at greater social responsibility have often emerged after scandal.

In fact, one of the discipline’s central parables is the redemption story of footwear and “athleisure” apparel giant Nike. In the 1990s, the company came under withering condemnation for outsourcing its manufacturing to sweatshops in Asia, where workers — sometimes children — received abysmally low wages, toiled with dangerous chemicals in inhumane conditions, and even faced physical abuse from management.

The scandal nearly brought Nike to its knees. Consumers boycotted the brand and activists held protests on college campuses and outside Nike stores.

Then, at the end of the 1990s, the company took decisive steps to clean up its act and make its labor practices more transparent. It began carrying out factory audits. It published lists of the factories with which it contracted and reports detailing wages and working conditions. It also raised worker salaries and sought to minimize the use of dangerous chemicals.

Most importantly for its reputation, CEO Phil Knight admitted Nike’s flaws and took clear public actions to correct them. In a 1998 speech marking the start of the transformation, Knight described the situation in uncompromising language.

“The Nike product has become synonymous with slave wages, forced overtime, and arbitrary abuse,” he said. “I truly believe the American consumer doesn’t want to buy products made under abusive conditions.”

This was actually a positive moment for the company, says David Crowther, a professor of corporate social responsibility at Britain’s De Montfort University.

After Nike’s admission, “sales went up and the share price went up,” he says. “People like honesty in companies.”

Ukrainian reality

For all CSR’s importance in global business, the concept is still developing in Ukraine. But local specialists agree that it is now an undeniable part of modern Ukrainian business.

According to Natalia Telenkova, a CSR specialist at audit firm EY’s Kyiv office, there are at least several dozen companies in Ukraine that “have a deep and correct understanding of CSR,” and they continue to develop. However, so far, Ukrainian CSR is not universally understood as necessary.

“This is not a problem of CSR, but of the immaturity of Ukrainian business on all levels,” Telenkova told the Kyiv Post.

Increasing social responsibility in business has also faced practical challenges. The collapse of the Ukrainian economy in 2014 has meant that companies have less money to spend on large-scale social projects.

At the same time, the reformist ethos of the EuroMaidan Revolution, which drove President Viktor Yanukovych from power in 2014, have helped to advance CSR, Telenkova believes.

“The understanding that it’s time for change has grown sharper,” she says.

The proof is in the practices. Saprykina, of the CSR Development Center, lists several projects that have demonstrated the positive role business can have in its local community.

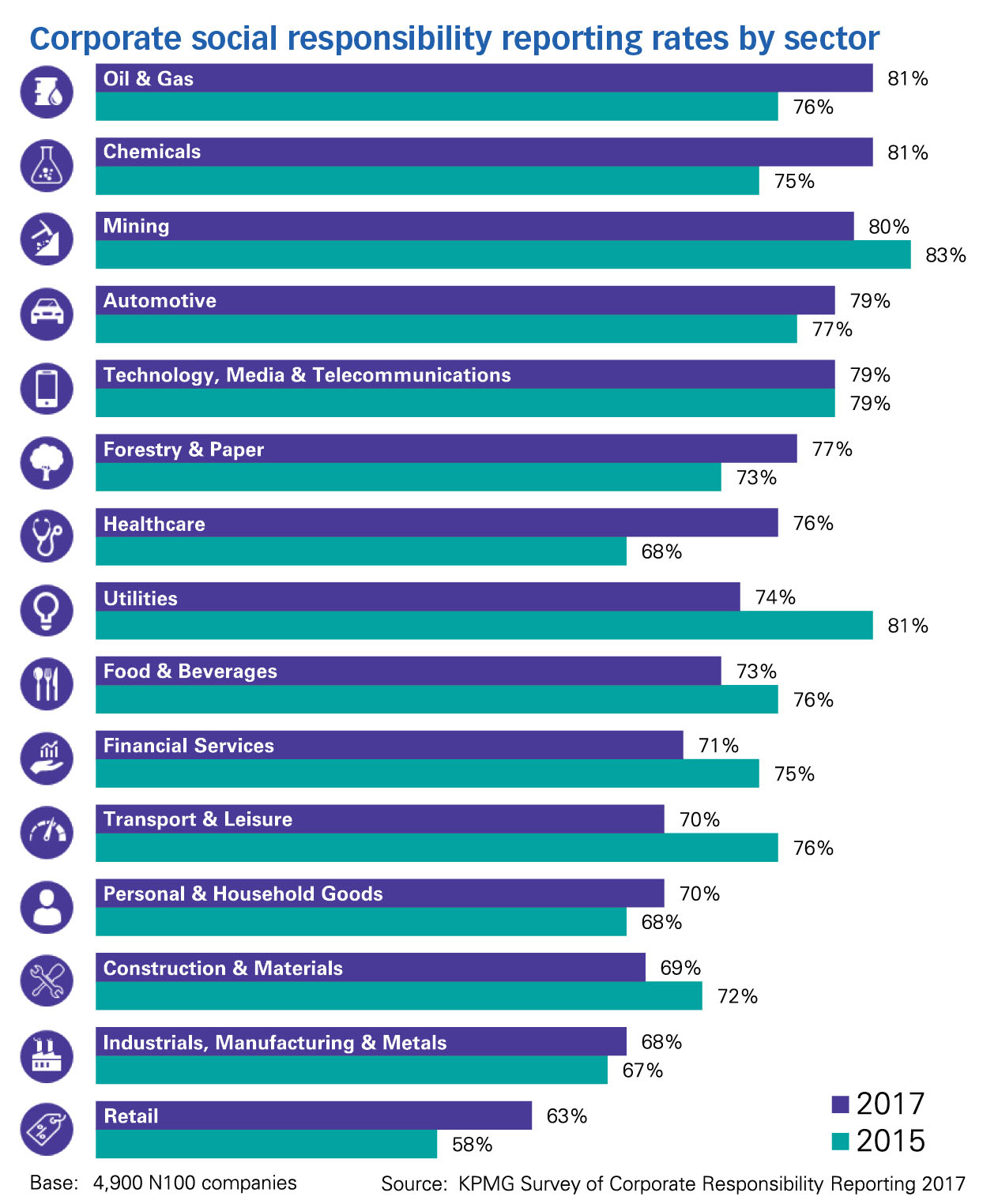

Sectors with high environmental and social impacts — such as oil and gas, chemicals, mining — tend to have high corporate social responsibility rates, according to KPMG audit firm. The sectors that showed the highest increase in reporting since 2015 are healthcare and chemicals.

For example, after the start of the war in Donbas in 2014, delivery service Nova Poshta launched a social project known as “Humanitarian Post Office.” The initiative allowed volunteer groups to send and receive humanitarian deliveries for free in any of the company’s branches.

In 2017, the company shipped more than 34,000 volunteer parcels to frontline zones. In the first quarter of this year, it has already shipped 7,617 such packages, Oleksiy Yatsiuk, who directs social projects for Nova Poshta, told the Kyiv Post in a statement.

In 2014, the company Galnaftogaz, which runs the OKKO network of filling stations across Ukraine, began gathering used clothing, household items, and books for impoverished Ukrainians.

The company installed drop off boxes at its enterprises and partnered with charitable organizations to distribute the donations to the needy. Currently, there are 18 boxes in six different Ukrainian cities.

And last year the Ukrainian branch of the French cosmetics company L’Oréal launched a program to train women who have suffered from domestic violence to work as hairstylists. The program helps socially vulnerable women start a new, independent life.

In fact, both Galnaftogaz and L’Oréal were selected as winners of a contest organized by the CSR Development Center with the support of EY and Germany’s Green Economy Platform.

But despite projects like these, Ukraine still lags behind in CSR.

As of 2017, only 65 percent of Eastern European companies carried out non-financial reporting that includes CSR, compared to 82 percent of Western European ones, according to a 2017 report by audit firm KPMG. The number of Ukrainian companies is smaller. Those publishing reporting that meets international standards is still in the dozens, Saprykina says.

However, starting this year, large European companies are required to include information on CSR in their annual reports. Ukraine is supposed to harmonize its financial legislation with the European Union’s by 2020, and there are currently attempts to work out similar CSR regulations for Ukraine.

What’s more, in 2017, Ukraine joined the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises. This agreement establishes a contact point at the Economy Ministry where any individual or organization can file complaints about a company violating human rights, breaking labor laws, and harming the environment.

Saprykina hopes this will help companies understand that their reputation is connected to sustainable business practices.

Two sides of CSR

Critics of corporate social responsibility argue that it is simply a strategy that allows businesses to whitewash their reputations and cover up any negative influence they exert on society. Meanwhile, advocates often speak about how CSR is an integral part of business without which economic success is impossible.

But the reality may be more complicated. CSR contains elements of both, but it is neither.

Experts agree that the public increasingly demands ethical practices from business. But, as EY’s Telenkova told the Kyiv Post, companies also use CSR to improve their image, achieve concrete advantages, and win the sympathy of consumers.

“Companies are pragmatic, and this is normal,” she says. “If a company pollutes the environment, and this is not controlled or stopped at the legislative level, the problem is not CSR.”

And CSR can help a company build up public support that may otherwise be out of reach. When the Prosecutor General’s office came to search Nova Poshta’s offices in a tax evasion investigation (the company denies wrongdoing), many people took its side.

“It was an unprecedented case for modern Ukraine when tens of thousands of people, including many thought leaders and leading entrepreneurs, came to the defense of our company and publicly stated their support for Nova Poshta,” CSR director Yatsiuk said.

But CSR is also not a panacea for a firm’s ills. At its core, it is an approach to doing business.

Studies strongly suggest that a focus on sustainability leads to greater profits several years down the road, Crowther says. But, contrary to the opinion of consultants, there is no single approach to this sustainability, and each company must set its own priorities.

In this regard, the case of ArcelorMittal and its labor standoff is not necessarily an example of failed CSR. Rather, the company is maintaining a balancing act.

“We understand that a huge mining and metallurgical company has a (negative) impact on the surrounding region,” Maiya Lastovetska, the company’s CSR manager told the Kyiv Post. “So we try to minimize this effect by carrying out social projects.”

The company invests in repairing schools, purchasing medical equipment, and repairing communal infrastructure. It also provides free English and IT lessons for its employees’ children.

The employees enjoy health insurance that Lastovetska says is quite good by Ukrainian standards. And ArcelorMittal has other benefits for its workers that are not common in Ukraine today — summer camps for employees’ children, vacation homes, recreation compounds.

But that does not necessarily undermine the workers’ demands, nor does it lend support to management’s position.

Fundamentally, Crowther says, one finds whatever they’re looking for in CSR — a PR gambit or a true desire for sustainability.

“As a business, you have got to evaluate the importance of various factors and mediate between them,” he says. “You can’t look after people and the environment and be highly profitable in all situations.”