Kyiv’s historical district around the Golden Gate became Sean Almeida’s golden goose since he set up his agency in Ukraine.

A veteran of the capital’s real estate, Almeida, 40, has been running his own real estate agency Vestor Estate for over a year, while living in Kyiv since 2012. The firm operates in a niche market — it provides properties to foreigners who have fallen in love with the charm of Kyiv’s old buildings.

But even though buying a historic flat in Kyiv is lucrative — foreign investors can expect double-digit yields in 10 years — Kyiv’s real estate suffers from old practices: ubiquitous cash and absurd expectations from sellers distort the prices and slow down the market.

Still, he believes foreigners shouldn’t hesitate to invest in Kyiv’s historical center. “The market suffers from massive inefficiency, but brave investors can catch quite good yields for that reason,” Almeida told the Kyiv Post.

Solid investment

Almeida’s agency offers central flats in tsarist, pre-revolution buildings built before 1917 and Stalin-era buildings from the 1920s to 1950s, with thick walls and ceilings up to 4 meters high.

“They might look rundown, but there are solid buildings that just need aesthetic renovation and some investment to increase their value,” he said.

Undervalued buildings come with the cost of renovation. New pipes, new electricity networks and ceiling reinforcement can be costly but their charm attracts Europeans and Americans. Expats who rent prefer older buildings because of their atmosphere while foreign investors appreciate their solidity.

Vestor closed up to 25 deals in 2020, with 90% of its clients buying apartments to later rent them out to foreigners.

Investors can see up to 11% returns on their real estate investment in less than 10 years in Ukraine. In Prague, the returns would be 3–5% and just 1–3% in Paris, depending on the property.

“We see here higher investment returns than in Western capitals,” Almeida said.

It’s a promising market for investors because thousands of foreigners want good quality housing, but there are not enough properties in the market for them.

“The supply of nice rental apartments is very low because it’s hard to get everything done in time, that’s why you see such high rent prices sometimes,” he said.

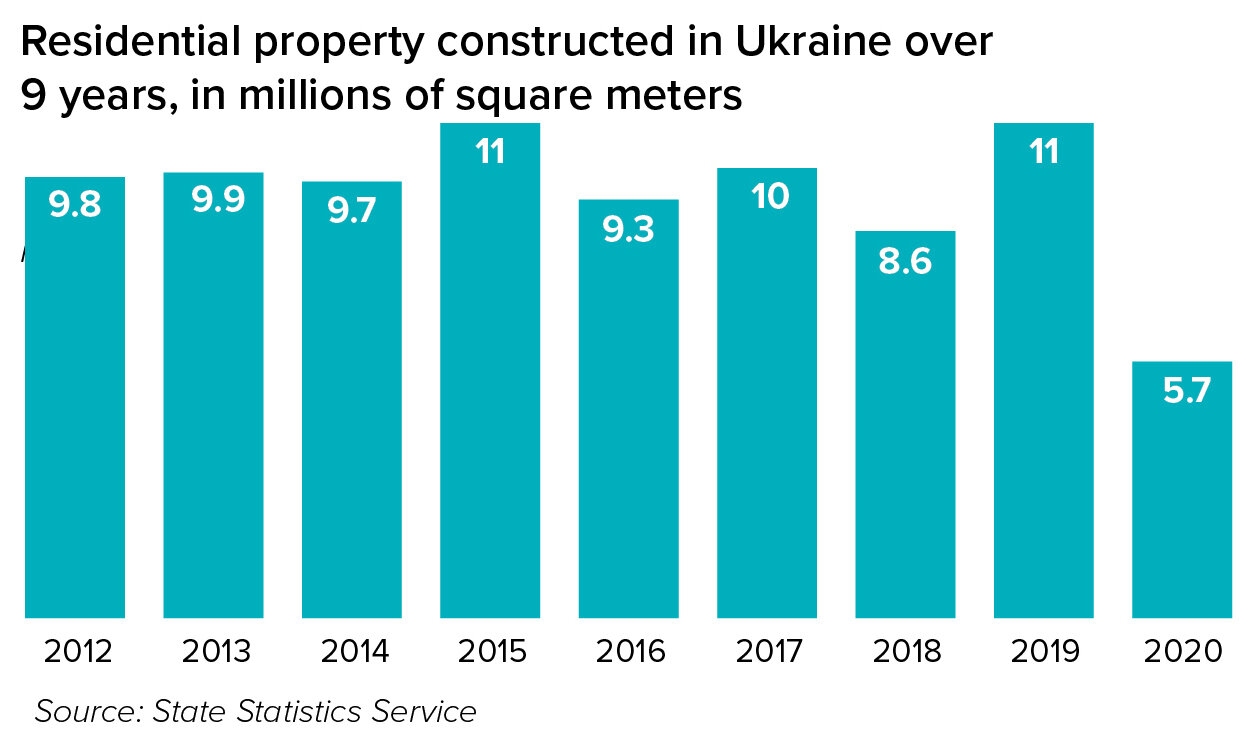

There isn’t enough residential real estate in Ukraine. According to estimates by construction firm Kyivmiskbud, there is an average of 20 square meters of living space per person in Ukraine, compared to the European average of 40.

Inefficient market

It is hard to get nice rentals onto the Ukrainian market because everything needs to be double-checked, Almeida said.

Ukraine doesn’t have an open data registry where buyers, sellers and real estate agents can check prices according to fixed criteria like the location or the way the property is built. Instead, real estate agencies often have to investigate and calculate the prices themselves which slows down deals.

“It’s difficult to know exactly what the market is,” Almeida said, “and data is only as good as what people put in there.”

The inputs of the market are skewed and this is linked to the history of Ukraine’s real estate, he said. The vast majority of Ukrainian sellers inherited the property from the Soviet Union, when authorities gave properties to their families. They don’t know the market prices and put unreasonable price tags, which complicates negotiations with buyers.

“They just want what they want and make up prices sometimes. It can be really difficult,” Almeida said.

Such expectations create a price discrepancy between similar properties, even when apartments are in the same building. One seller might be asking $2,000 while another would ask for $8,000 — for an apartment of the same area.

Such differences distort the market’s data, making the average price higher than it should be, Almeida said.

Ubiquitous cash

The prevalence of cash adds up to the difficulty of setting prices. Local sellers distrust Ukrainian banks and prefer to be paid in cash, which leads to misleading sales.

With a 7.5% total closing costs including 1% taxes, Ukraine’s real estate taxes are already low, but some sellers want to pay even less, reducing the real price and paying part of the property sale in cash under the table.

Such transactions add up to the opacity and inaccuracy of the market in Ukraine, Almeida said.

Meanwhile, banks have to adapt their policy too. Almeida’s agency uses bank transfers to close transactions, but it’s not a widespread phenomenon because banks tend to be suspicious when large amounts of money are involved.

While making transactions, “we had to explain to banks that such transfers were beneficial to them too. A lot of banks were suspicious at first transferring such amounts of money,” he said.

In 2020, banks started allowing dollar-to-dollar transfers within the country as long as one party is not a resident.

If a foreigner buys a property, they can open a Ukrainian account in dollars that’s dedicated to the purchase. They can then transfer the payment to the seller in dollars. This makes life a bit easier by “limiting risks and cutting down the time of a single transaction,” Almeida said.

Overall, Almeida is optimistic about the market’s evolution, especially concerning corruption. Ukraine’s real estate is safer than people think because individual properties are too small to involve any kind of corruption schemes, he said.

“If you’re a foreigner and want to buy a real estate property in the center properly, with bank transfers and having a lawyer — don’t hesitate,” Almeida said.