CBRE Ukraine is doing fine. Ukraine’s real estate sector, not so much.

While Ukraine is not in the worst of times, the best of times would require tough but obvious fixes, said Sergiy Sergiyenko, one of CBRE Ukraine’s two managing partners in an interview with the Kyiv Post.

‘Always something new’

Sergiyenko has been with Ukraine’s office since its start in 2008 and stays for two reasons: He’s found no better employer, praising CBRE’s high ethical standards, and he still finds real estate challenging after 21 years in the sector. “There’s a whole world of real estate everywhere you go,” he told the Kyiv Post in an interview. “There’s always something new to see.”

Sergiyenko, nonetheless, said Ukraine’s real estate sector is limited by a feeble property tax system, lack of competition in the construction industry, high-interest rates on loans and bad municipal planning. If he could wave a magic wand, here’s what he would change:

Property taxes

“I would copy/paste the American system, which is extremely efficient. It eliminates frozen construction. It eliminates unused properties. It promotes the highest and best use of properties. It promotes redevelopment when the property becomes obsolete. It’s extremely efficient. “The Ukrainian system is a Soviet/post-Soviet one. We have difficulty imposing taxes because they’re extremely unpopular. And even if you impose taxes, then people find ways to go around them. People don’t want to pay the government because they know the money will be siphoned out. From my limited experience, the government’s efficiency is about 15 percent. So, if you pay $100 to the government, realizing that $85 will be stolen, you are very resistant to paying taxes.”

Lack of competition

“There is a close circle of good old friends that to a large degree influence who can do what. I am not a professional of construction and development. We watch it and here it from the developers themselves. The bigger and the more capital intensive, the more central location, the narrower circle you have to do with. They have to have a share in the game or it doesn’t work. I would prefer it to be more laissez-faire. But unfortunately, it’s not.” Asked who he is talking about, he replied: “When I retire, I will name names.”

High-interest rates

“In Ukraine, the cost of credit is totally prohibitive,” Sergiyenko said. “You cannot develop taking a loan in Ukraine even if it was available.”

The absurdity of the lending market, he said, is highlighted by a $5-million bank loan at a 20 percent annual interest rate that the Arricano real estate development company took out this year to complete construction of the Lukianivka shopping and entertainment center in Kyiv. As long as Ukraine remains a high-risk county with little investment and low currency reserves, Sergiyenko doesn’t expect interest rates to become affordable soon.

The lack of credit creates many distortions in the real estate sector. It means that most who build or buy do so with their own equity or savings. On the commercial side, this favors big and established builders. Oddly, however, the banking instability is a boon to the housing sector. “Residential real estate is just a substitute for the normal functioning of capital markets in the developed countries,” Sergiyenko said. “You don’t have any stock exchange here, so you put it into real estate. It’s a byproduct of a dysfunctional financial system.”

Bad municipal planning

“Most of the people who are responsible for city planning are still Soviet. They change a tweak a little here and there, but there is no wholesome change to the entire planning approach,” Sergiyenko said.

This leads to bad situations, including block after block in Kyiv’s city center where numerous old buildings are vacant and decaying while high-rise apartments are jammed together on the left bank and other distant districts. Besides the failure to adopt an American-style property tax system, Ukraine also does not use the powers of eminent domain to force building owners to repair or remove blighted properties. Additionally, many abandoned buildings are legally protected as historic sites, but the owners have no intention of fixing them and let them rot or burn them down.

So what’s ahead? Here’s Sergiyenko’s overview of the commercial property sector that he specializes in:

Office sector

The market is dominated by Kyiv, with Lviv “now becoming the main second city,” followed by Odesa, Dnipro and Kharkiv. The office sector “is coming back,” but “it is so small and so tiny compared to where it needs to be. Once there is a little bit of economic development, it gets consumed immediately. There is a bottleneck. Prices go up and development begins. But the market is so sensitive to macroeconomic fluctuations. Once things turn for the worse, everybody immediately closes down, reduces, cuts, and there are huge vacancies. Here the fluctuations are very wild and they lead to a lot of bankruptcies.”

And so buyers like Dragon Capital find bargains in buying foreclosed properties from banks that “wanted to get rid of them,” he said. “Why isn’t Dragon developing properties? Because it’s a lot cheaper to buy than to build, which is totally the reverse from a developed market,” Sergiyenko said. “When it becomes cheaper to build than to buy, then we will have a development wave.”

The rental number to watch in office space is $25 per square meter, which the market is approaching. “We see active development at $25,” he said. But overall, the 150,000–200,000 square meters of new office space demanded per year in a growing economy is “not being met with new construction.”

Retail

While e-commerce has killed off countless malls and stores in the West, Ukraine keeps building shopping and entertainment centers, seemingly bucking the trend. Why? “Retail is the most nationwide network,” he said. “Shopping centers are being built because e-commerce is still very undeveloped, even though we have Rozetka here. Another reason is that because the municipal infrastructure is such shambles, where do you go? There is nowhere to go, so people go indoors to a public place that has been privatelydeveloped for the sake of the experience: to hang out, drink coffee, watch a movie. There is no entertainment outside of shopping centers to a large degree.”

Also, the purchasing power of Ukrainians is on the rise from the depths of the 2013–2014 recession, so retailers have hope.

Industrial/warehouse

“Warehouse is completely connected to retail,” Sergiyenko said. “Once retail grows, warehouse grows with it. Once it shrinks, it shrinks with it. There is very little vacancy in the warehouse market. At the same time, because of no credit, rental rates have to be extremely high to justify new construction.”

At today’s rates, he said, “we are not quite there yet” to justify the building of much new space.

“The construction costs here are higher than in Europe. A lot of materials have to be imported. You don’t have reliable contractors.”

‘Bright side to everything’

“There is a bright side to everything. We’re growing. Everyone wants to grow. There is development coming from a certain number of established players who understand how to operate in this environment. So we are headed for a bottleneck. The market is not at a standstill, but it’s in a slow-motion mode ahead of elections.”

About CBRE Ukraine

The Ukrainian office of CBRE was opened in 2008 in Kyiv. It is part of the affiliate network of Los Angeles-based CBRE Group, Inc. CBRE Ukraine has 300 employees and manages 800,000 square meters of shopping centers and industrial space, as well as 20,000 square meters of corporate real estate.

CBRE Ukraine provides advisory, management, transaction, valuation and other services in the commercial property sector. The website lists more than 30 clients, including: Arricano, Baker McKenzie, Deloitte, DHL Ukraine, Dragon Capital, Nokia, and numerous banks. The global group is the world’s largest commercial real estate services and investment firm, with more than 80,000 employees and 450 offices worldwide, excluding affiliates.

Kyiv real estate, by the numbers

Office: 1.8 million square meters

Retail: 1.3 million square meters

Hotels: Over 110 hotels with a total room stock of 10,800 rooms. Four hotels were added with 794 rooms.

Residential: 1.1. million apartments, 63.5 million square meters; 22 square meters per resident, The average price per square meter in July 2018 was: economy — $683; comfort — $1,057; business — $1,587.

Sources: Ukrainian Trade Guild, Cushman & Wakefield, JLL, CBRE, Colliers International.

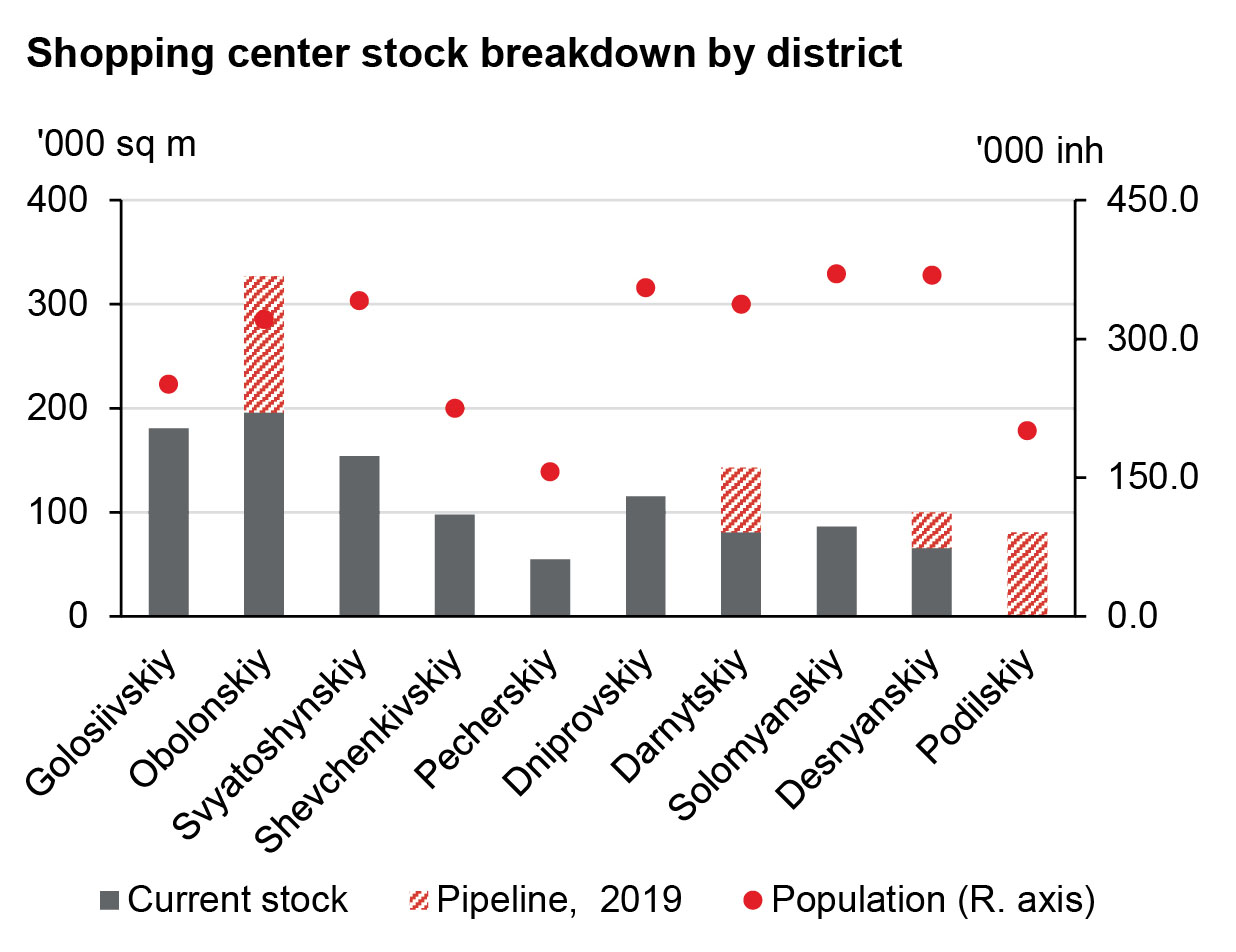

Kyiv’s real estate market has been growing at a slow yet steady pace during the past few years. The retail sector has been on the rise as the purchasing power of Kyivans increases. Holosiivskiy, Obolonskiy and Svyatoshinskiy districts are among the more popular districts.