For businesses in Ukraine, avoiding taxes has long been one of the ways to remain competitive and circumvent bureaucracy.

Businesses still frequently pay full or partial salary in cash. The “envelope salaries” allow them to avoid a 41.5 percent tax on wages – the combination of income and other payroll taxes. Other times, employees register as “individual entrepreneurs,” like contractors, who are only required to pay a 5% tax on their income.

Speaking at the Ukraine 30 “Labor Resources” forum on July 21, Economy Minister and First Deputy Prime Minister Oleksiy Lyubchenko estimated that unreported wages amount to $18.6 billion every year.

As a result, the country loses out on billions of dollars of taxes every year. Without this revenue, the government cannot extend pension funds and unemployment benefits to those who really need it, diminishing the state’s ability to help its population.

The State Labor Service of Ukraine along with the State Tax Service are trying to step up the fight against the shadow economy. Since July, they have teamed up to conduct large-scale audits of businesses to identify employees receiving unofficial salaries. They want to “encourage taxpayers and employees to transition from informal to declared employment.”

In just a month, more than 4,064 undeclared workers were identified while performing almost 1,400 inspections. The largest number of unofficial workers were found in Zaporizhzhia (11%), Vinnytsia (9%) and Khmelnytskyi (7%) oblasts.

But the two state agencies may find it difficult to curb this problem. Yuri Gaidai, senior economist at the Center for Economic Strategy, says it is extremely difficult to spot unofficial employment in Ukraine, and businesses are hardly afraid of fines ranging from $2,000 to $7,000 for paying employees unofficially.

“To businesses, the benefits of avoiding tax currently outweigh the likelihood of being caught and paying fines,” Gaidai said.

Ukraine’s shadow economy is still large as employers and employees alike pursue legal and illegal ways to avoid taxes, which business advocates say are too high and too onerous to encourage compliance. Moreover, given Ukraine’s high level of corruption, many people avoid paying taxes because they are not confident that public officials will spend their money for the public good.

Hard to see in the dark

According to Igor Dehera, deputy head of the State Labor Service, every fifth Ukrainian works unofficially, receiving part or all of their wages in cash.

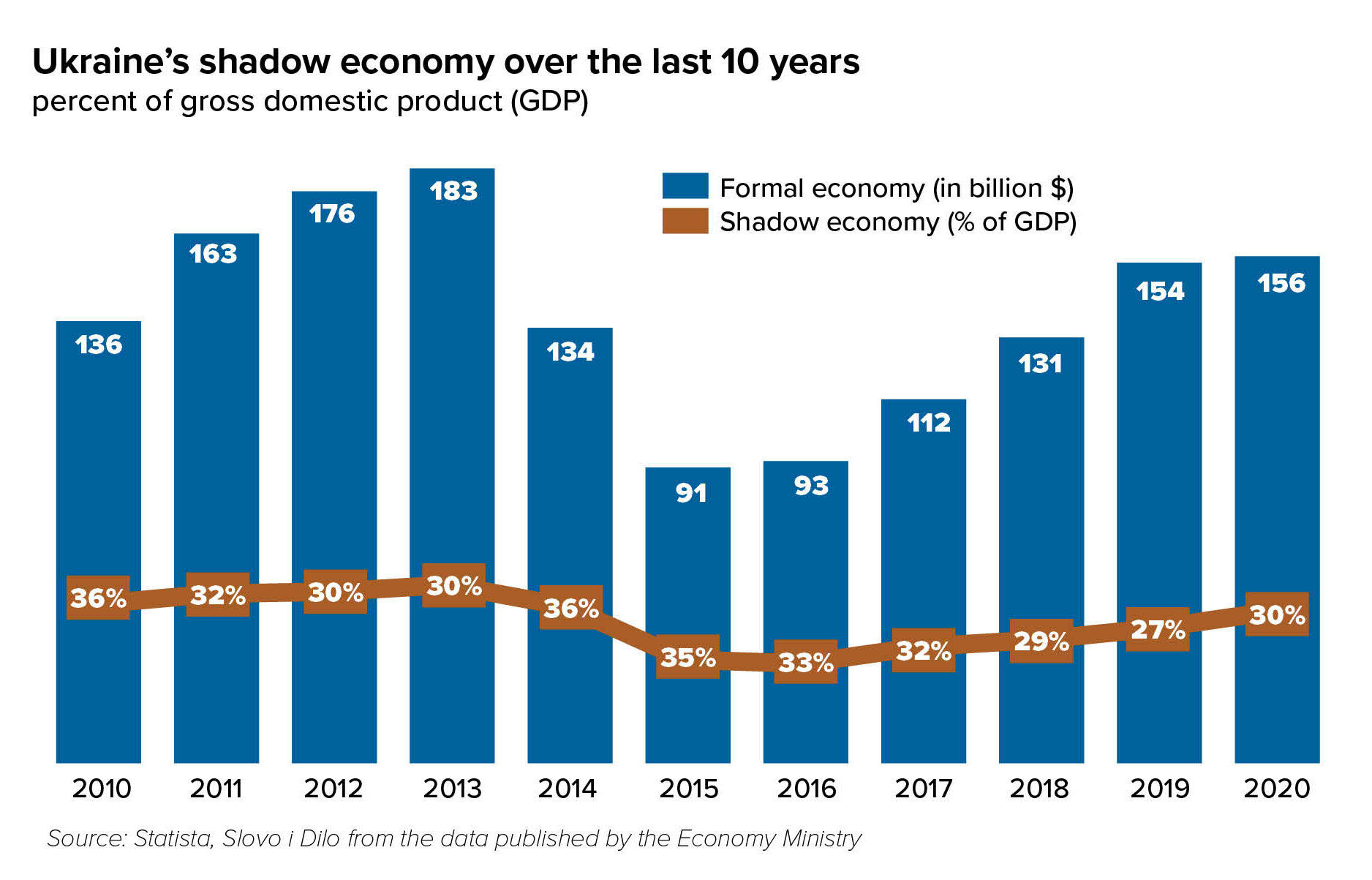

And this number is growing. Lyubchenko said that the shadow economy in Ukraine made up 30% of its gross domestic product in 2020, an increase from 27% in 2019.

But as the true share is difficult to measure, some, such as Danil Getmanstev, head of parliament’s finance and tax committee, estimate the share to be closer to 50%.

For employees who are paid in cash, being unofficially employed means they are deprived of the guaranteed social benefits, which include pensions, medical care and unemployment benefits.

In times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, many unofficial employees were not protected as they had never signed a contract and were therefore ineligible for unemployment benefits.

The consequences extend to pensioners, who rely on the state for their income. There are more than 11 million retirees whose pensions depend on legally working citizens.

Only 11.3 million Ukrainians received an official salary in 2020, according to Lyubchenko. In a country with a population of 43 million, this is a far cry from the amount needed in order to support an aging population.

Denys Shendryk, head of the tax and legal department at Mazars Ukraine, an international audit, tax and advisory firm, says that these practices have consequences not only on the state’s ability to collect taxes or provide for its citizens but reduce overall trust in Ukrainian businesses.

“These practices can turn away potential partners and investors who will have a difficult time trusting the company. If you are not fair with your employees and tax authorities, why will you be fair with me?”

Denys Shendryk, Head of Tax and Legal Department at Mazars Ukraine, an international audit, tax and advisory firm, speaks with the Kyiv Post on July 16 in his office in central Kyiv. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

Change won’t come easy

Anna Derevyanko, executive director of the European Business Association, told the BBC in April that the tax burden on wages is “one of the biggest problems in Ukraine,” and the reason why many businesses don’t pay salaries officially.

According to her, the 41.5% tax is simply too high for many businesses to afford. This is why many businesses, especially IT companies, opt to classify their employees as “private entrepreneurs.”

Like unofficial employees, private entrepreneurs also don’t have access to benefits such as pension and unemployment funds. However, according to Gaidai, this tax regime is a way for small businesses to grow, providing them flexibility in hiring whilst avoiding heavy tax burdens.

The question is less about whether the private entrepreneur status should disappear and more about finding a way to protect these workers. The simplified tax regime should stay in place but needs to be adjusted to “avoid abuse by bigger players,” Gaidai said.

And while the State Labor Service of Ukraine along with the State Tax Service may be planning to increase audits on companies in an effort to curb unofficial or partial employment, the state also has to figure out a way to reduce the tax burden on companies.

For one, experts agree that the social tax that goes mostly to pensions, which is 22%, should not be increased — it needs to be decreased instead.

Shendryk believes that improving the country’s tax culture is about encouraging businesses to do their part. He said tax authorities need to interact with taxpayers better when making further changes in tax legislation.

“The recipe of success is a cooperation of businesses and authorities,” Gaidai said.

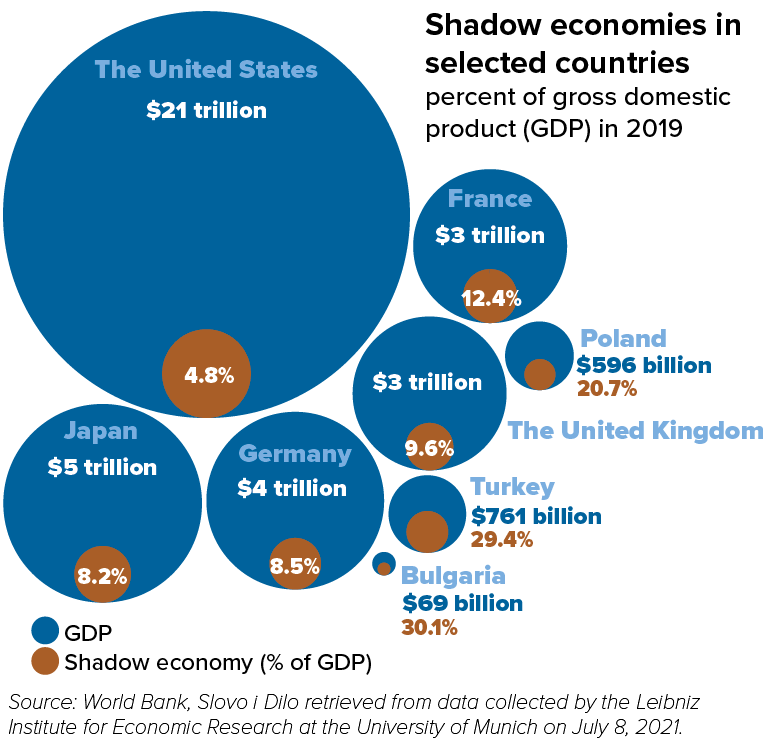

In 2019, the size of Ukraine’s shadow economy was estimated at 27% of the country’s gross domestic product, smaller than in neighboring Bulgaria and Turkey. However, Ukraine missed out on an estimated $42 billion in shadow economy in 2019.