When most of Europe is struggling with an influx of refugees, Turkey has achieved a success story.

Turkey’s humanitarian assistance has diversified and significantly increased in recent years, mainly in response to the bloody seven-year-old Syrian civil war.

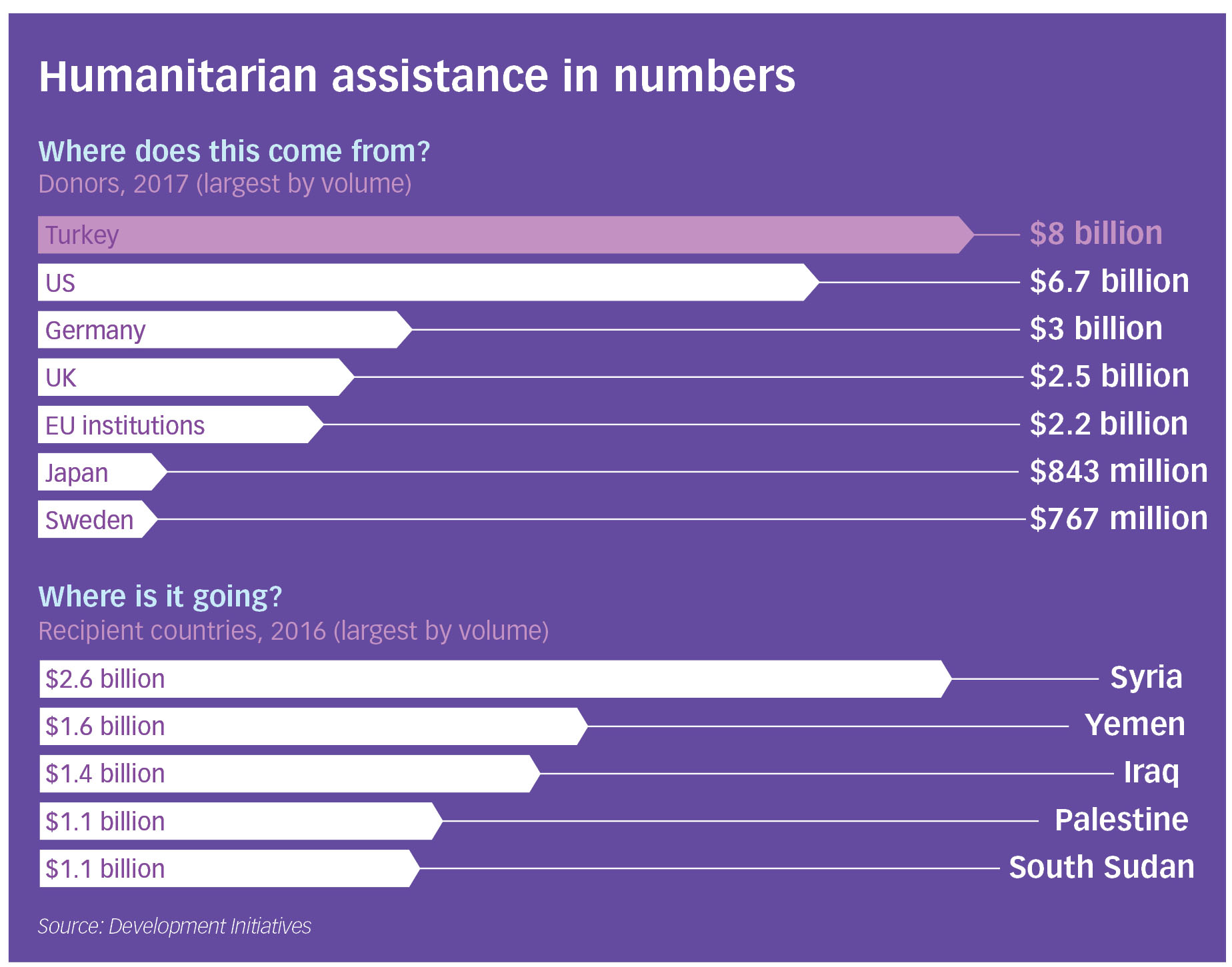

In 2017, according to the Global Humanitarian Assistance Report, Turkey ranked as the largest donor country worldwide with its $8 billion in assistance. Turkey also ranks first when the ratio of official humanitarian assistance to national income is taken into account.

Turkey now hosts 3.5 million refugees from the war in Syria, while the whole of Europe has about 1 million of them. The total number of refugees in Turkey is 4 million, which is the single largest refugee population in the world.

And Turkey controls parts of Aleppo and Idlib provinces, one of the last bastions of Syria not under the control of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad.

Mehmet Gulluoglu heads the Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Authority. It is a special government body for disaster and risk reduction, which oversees the response to internally displaced persons in Turkish-controlled parts of Syria. The authority also was in charge of refugees in Turkey until six months ago.

Gulluoglu said that Turks and Syrians are able to adapt to each other more easily because of the shared Muslim faith and other cultural links.

When confronted with a humanitarian crisis, his agency needs to constantly adapt, he said.

“What we are doing is between life and death. What we are doing is needed urgently,” Gulluoglu told during his interview with the Kyiv Post on Oct. 19.

Turkey’s help to Syria

The civil war in Syria — or revolution against the Assad dictatorship — started in March 2011. More than 500,000 people have been killed, by estimates of the British-based information office Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

The conflict prompted 6.6 million people flee to other parts of Syria and forced 5.6 million people go abroad, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency. It was about a half of Syria’s pre-war population of 12 million.

Gulluoglu has worked with the Syrian conflict for the last five years initially as a general manager of Turkish Red Crescent and then as head of the Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Authority.

He said that, in the first months of the Syrian war, Turkey established 21 refugee camps by the Syrian border. But now these camps are half-empty and 96 percent of Syrian refugees live outside of the camps in different parts of Turkey. The number of refugee camps has been reduced to 16, and they host only some 150,000 refugees, predominantly elderly, sick and disabled and families in need.

“Different authorities are now discussing on how much we still need these camps,” Gulluoglu said.

Turkey, whose humanitarian aid is predominantly the expenditure on hosting Syrian refugees, was the largest humanitarian donor in 2017. Syria was the largest humanitarian recipient.

He said Syrians live predominantly in the cities close to the Syrian border, including Urfa, Gaziantep, Kilis, and also in Istanbul, the country’s largest city, where it’s always easier to find a job. The refugees enjoy free medical and education services in Turkey if they get registration.

Many refugees are involved in the traditional crafts for which Syria has been always known for, including textile, shoemaking or furniture making. So they find jobs in the places which need workers in this area.

It is, however, much harder for educated specialists, like doctors and engineers, to find the jobs because apart from the language they have to prove those diplomas.

Refugee challenges

While the Syrian refugees are tolerated by most of the Turkish society, some tensions emerge, however, when the locals see in them competitors for jobs.

Gulluoglu admitted regional differences in perception of the refugees.

“In border cities, Syrians are much better accepted because the culture is similar and there are many mixed families. But in the western side (of Turkey) the culture is different that’s why the perception also is often different,” he said.

Syrian children, who go to local schools, now freely speak the Turkish language. So in many families children accompany those parents to translate for them in the shops and different services, Gulluoglu said.

But while the total number of Syrian refugees in Turkey is equal to the population of a big city, it’s hard to predict how many of them will ever return to Syria.

As of now, just 250,000 refugees came back to the Turkish-controlled areas of Syria, according to Gulluoglu.

Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan said in September that Turkey would stop accepting of the new refugees from Syria.

Gulluoglu explained that for the last two years the Turkish government restricts come of the new refugees from Syria offering them to stay instead at the Turkish-controlled parts of Syria.

“Most residents except for those in need of extra health care services should stay in Syria where it’s safe now,” Gulluoglu said.

According to the questionnaires conducted by AFAD, more than half of the Syrian refugees plan to go back home, he added.

IDPs in Syria

In the Turkish-controlled part of Syria, there are millions of IDPs, coming from Aleppo and other areas destructed by war.

The Turkish government is restoring the infrastructure to attract Syrians return to this land. It has already cost Turkey more than $30 billion to rebuild infrastructure and help refugees in Turkey, Gulluoglu said. But this money is not enough.

“At least $200 billion are needed for rebuilding Syria. There are thousands and thousands of buildings in ruins. If you cannot give people houses and infrastructure it’s not easy to expect them to go back,” he said.

In Idlib Province, the hottest part of Syria, which is now mostly controlled by jihadists and the Syrian opposition, the fights are still going on. The big offensive is looming and it may cause new deaths and destruction.

Gulluoglu said the humanitarian crisis can’t be resolved without the political solution and puts the blame for the current devastating situation on the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

“Will Asad and his family stay in power? If they insist on staying, there will be hard to find political stabilization,” he said.

Lessons for Ukraine

Gulluoglu said he understands Ukraine’s government has 1.5 million refugees from Donbas and Crimea, who had to flee those homes as a result of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

“Just like in Turkey, the one side of it is a political side, another one is humanitarian side,” he said.

He said each year the needs of internally displaced persons are changing and “the government should be aware of that” and be ready to adapt to new reality.

Just like in Syria, restoring the infrastructure and creating the new jobs is vital to improving the lives of these people and easing social tensions, Gulluoglu said.

He believes creating new jobs is more efficient and even cheaper than just granting humanitarian aid.

“If the government encourages people to engage in economic activity it makes a sustainable presence there, decreases dependency and, from a long-time perspective, it costs less than just helping,” he said.