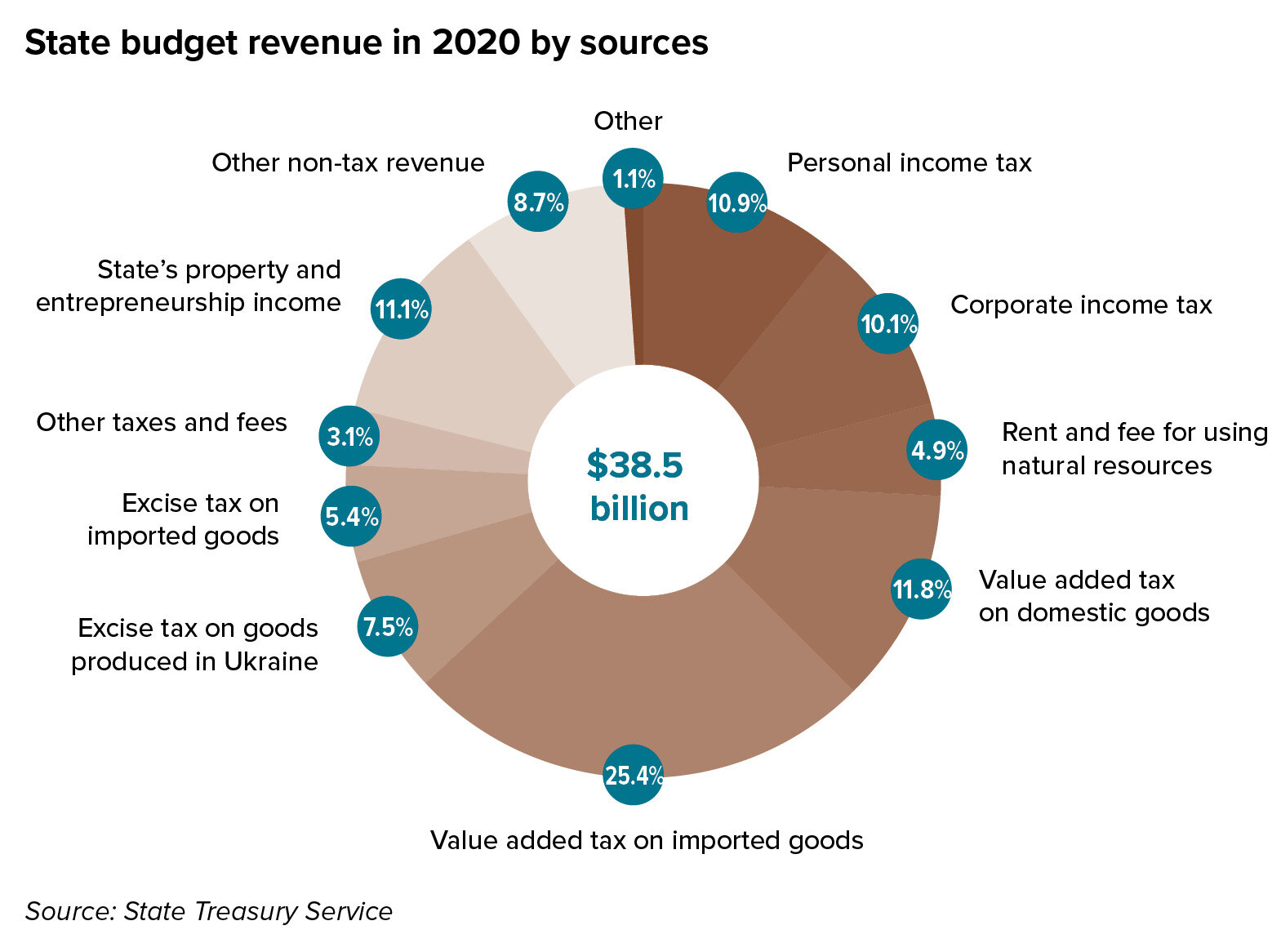

Most tax revenue in Ukraine comes from social tax, personal income tax and value-added tax. Combined, taxes account for 79% of the country’s state budget revenue, or $31 billion.

In 2020, Ukraine collected $38.5 billion through tax and non-tax revenue. Much of it came from value-added tax on both imported and domestic goods — 37.2%. The state budget approaches $50 billion; the remainder is financed by borrowing.

Employers’ 41.5% commitment

Employers in Ukraine pay three taxes on every salary: a social tax, an income tax and a military levy (introduced in 2014). In total, a company pays 41.5% in taxes for one employee.

Tax experts agree this combined rate is too high. Vladimir Dubrovsky, a senior economist at CASE Ukraine, a think tank for social and economic studies, said that the current rate encourages employers to evade taxes.

As a result, many enterprises either pay their workers off the books, in cash, thus lowering the reported official salary and paying less in taxes, or ask their staffers to register as individual entrepreneurs to be able to pay a modest 5% individual entrepreneur tax.

Employers who want to be 100% legal are overburdened with taxes and may not outcompete their less conscientious counterparts. “It’s like punishing an employer for creating jobs and paying salaries,” Dubrovsky said.

Value-added tax

Currently, there are three VAT rates in Ukraine: 20%, 7%, and 0%.

The reduced rate of 7% applies to export and import of specific medical goods and medical equipment that’s used in clinical trials. Starting in 2021, this rate is also applied to some services, including holding cultural events and arranging excursions in museums, zoos and natural reserves.

The 0% rate applies to the supply of international transport and toll manufacturing services (if the finished goods are then re-exported from Ukraine), and some other services.

The 20% rate applies to the rest of the transactions that are subject to VAT. An electronic system to collect VAT and anti-tax evasion measures created a more transparent environment, when it was introduced in 2015, Serhii Popov, head of the tax and legal desk at auditor KPMG, told the Kyiv Post.

Property tax

The local property tax, meanwhile, is still relatively new and undeveloped unlike in many Western countries, where property taxes provide the backbone of local budgets, often accounting for more than half of tax revenues.

In Ukraine, property tax contribution is worth only 3% of revenues. The State Treasury Service doesn’t even have a separate category for property tax and combines it with other personal income tax revenues, which together secure 10.9% of the budget.

Unlike in other European countries like Germany where the rate is determined by the assessed value of the property, Ukraine’s system is based on the size of the apartment or building.

Much of Ukraine’s state budget revenue in 2020 came from value added tax on both imported and domestic goods, which comprised 37.2% of the total $38.5 billion collected through tax and non-tax revenue. The state budget, however, approached $50 billion. The remainder was financed by borrowing.

Are changes needed?

The government plans further changes to the tax legislation, which includes an increase in the tax on natural resources and excise tax on a number of goods, according to Alexander Cherinko, head of the tax & legal department at auditor Deloitte Ukraine.

But Cherinko doesn’t think massive changes are required. He said Ukraine’s focus should be on building trust in a relationship between taxpayers and tax authorities, rather than changing legislation.

More businesses, meanwhile, have come to understand the importance of auditing, since the new law on auditing was passed in 2018, said Gregoire Dattee, a partner at Mazars in Ukraine. According to the expert, more companies are subject to mandatory audits today, which helps foster trust and transparency in the business market.