When massive fires broke out in the Chornobyl exclusion zone in April 2020, state officials only sounded the alarm when the smoke reached Kyiv, covering the sky with dust. In six days, over 3,000 hectares of land burned — the equivalent of 4,200 soccer fields.

Ukraine could have acted more quickly if its satellites had spotted the first signs of the blaze, according to Volodymyr Taftay, chief at the State Space Agency of Ukraine — the Ukrainian government agency responsible for space policy and programs.

But Ukraine doesn’t have its own satellites. Instead, it spends thousands of dollars buying data collected by Europe, China or the U. S. This reliance is especially troublesome when it comes to sensitive information like troop locations in the war zone of the eastern Donbas.

“Regular observation from space helps to identify the root of the problem, saving money for the state,” Taftay said.

The absence of satellites is just one of many problems that the Ukrainian space industry has. Its massive rocket factories are outdated and unprofitable; the country is yet to approve a space program that allows its enterprises to attract finances or execute orders from the state; a small market discourages private companies from developing space technology.

Taftay says this year will be different for the Ukrainian space industry. The country plans to launch its first satellite in 10 years this December and to approve its space program by the end of the year.

Given that private investment in the global space businesses hit a record $4.5 billion in the second quarter of 2021, fueled by the space race of billionaires Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, Ukraine has to revive its space industry, and fast, in order to keep up.

“As long as we are not moving forward while our competitors are, we are actually moving backward,” said Volodymyr Usov, former Space Agency chief.

Lucrative industry

If space was once a political tool for world’s superpowers, today it is also a business opportunity for a new generation of entrepreneurs all over the world, including Ukraine.

Last year international private space companies attracted a record $9.1 billion to launch Earth monitoring or communications satellites into orbit or to build spacecraft that deliver people and cargo to space.

Investments in space are long-term and risky, Taftay said, but they pay off in the future.

“The space industry brings in seven times more money than it receives. For every dollar invested in the space industry, the country’s economy receives $6–7 in taxes and investment,” according to him.

As of today, Ukraine has 10 private space companies, Taftay said. Most of them — like Firefly Aerospace, Skyrora and Dragonfly — have become international stars and are now based in the U.S. or U.K., working with NASA and SpaceX.

But many Ukrainian space businesses export their products abroad because there is no money or work for them in Ukraine. “You can create your own space company here, but it is unclear what to do with it next. Who will be the customer?” Usov said.

In the U.S., nearly 80% of orders for space businesses come from the State Department or the Department of Defense, according to Usov. NASA astronauts even flew to the International Space Station on the Crew Dragon spacecraft manufactured by SpaceX.

For many decades Ukraine has only worked with state-owned enterprises like Pivdenmash and Pivdenne on its space projects. “This business model discouraged the development of new private companies,” Usov said.

To change this, the government passed a law in 2019 that allows private companies to build spacecraft in Ukraine and compete for contracts with state-owned enterprises or work together with them. In 2019, for example, Ukrainian-American aerospace company Firefly Aerospace ordered $15 million worth of missile parts from Ukrainian Pivdenmash.

But these agreements are rare. Ukraine’s main customer — the government — hasn’t yet signed any big contracts with private space companies. “There are no orders because we haven’t had financing or even a space program since 2018,” Taftay said.

$1 billion space program

Without a governmental space program, the Ukrainian space industry is frozen: “It hasn’t had any priorities, nor the conditions to develop,” said Oleg Uruskyi, the minister of strategic industries.

As a result, state-owned space enterprises have become less productive over the years. In 2018, state-owned space enterprises brought Ukraine $42 million in taxes, in 2019 — $34 million, in 2020 — $32 million. Last year was the most unfortunate for the Ukrainian space industry, according to Taftay.

Out of the country’s 15 state-owned space enterprises, five were loss-makers last year, four went bankrupt and one fired all of its employees. Together, they lost $30 million in 2020 compared to $16 million in 2019 and $2.7 million in 2018.

The space program submitted by Taftay will cost Ukraine over $1 billion — only half of this money will be covered by state funds, the other half — by export contracts.

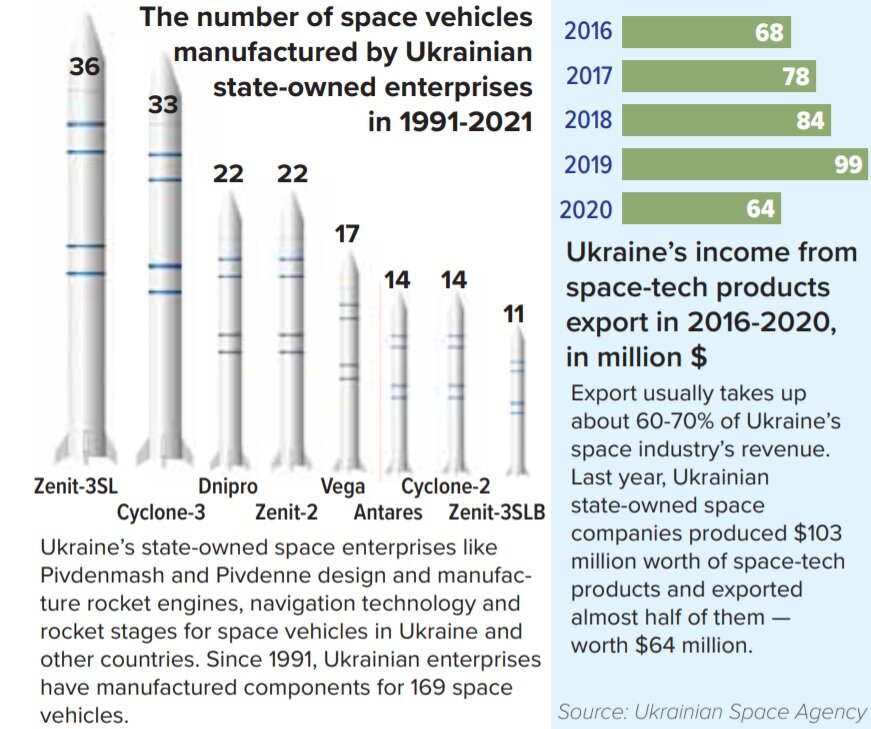

Last year Ukrainian state-owned space companies produced $103 million worth of space-tech products and exported almost half of them — $64 million. Export usually takes up nearly 60–70% of the industry’s financing, according to Taftay.

Many European countries and the U.S. order Ukrainian-made rocket engines, navigation technology and rocket stages because they are cheap and reliable.

In the last 30 years, Ukrainian state-owned enterprises manufactured the components for 169 carrier rockets, including Cyclone, Zenith, Antares, Vega. These rockets launched 449 international spacecraft into orbit.

As of today, Ukraine only has two big international projects to rely on — the assembly of the first stage cores for NASA’s rocket Antares and the production of cruise propulsion engines for the European Space Agency’s rocket project Vega.

But they will not last forever, Usov said. Ukraine will need to secure more contracts with international partners but without a space program, it is impossible to do, according to Usov.

“Ukraine is still enjoying the perks it has gained in Soviet times — but it isn’t evolving. Other countries, in turn, invest in innovations and are catching up with Ukraine,” he said.

Future changes

To regain its power on the global market, Ukraine has to boost competition inside the country — between state-owned behemoths and private companies, according to Usov.

Today, the country’s space enterprises like Pivdenmash and Pivdenne in Dnipro, Kommunar and Hartron in Kharkiv or Kyivpribor in Kyiv cannot control their own assets or attract investment. They are also burdened by outdated infrastructure and a bloated workforce.

The giant Pivdenmash spaceship factory, which in the 20th century manufactured the most powerful rockets in the world, suffered $25 million losses in 2020. As the number of orders for its products has been decreasing, the factory descended into crisis: it didn’t have water for weeks, its sewage system didn’t work and employees weren’t paid properly.

To save state enterprises from the crisis, Ukraine plans to turn them into joint-stock companies, Taftay said. “It will make them more flexible and attractive for investors.”

Within the new space program, state enterprises will compete with private companies for the right to build six satellites — two each year starting in 2023, Taftay said. But first, Ukraine plans to send up the Sich 2–30 satellite in December using the U.S. launch vehicle Falcon 9 that belongs to SpaceX.

Ukraine will pay Elon Musk’s company $1 million to launch the satellite — eight times lower than planned. Ukraine will send the assembled satellite to the spaceport in the U.S. by plane, at the beginning of November, according to Taftay.

With this satellite, Ukraine could collect data to forecast crops and detect problems in the fields, analyze the usage of minerals and water, monitor the movement of troops.

Sich 2–30 was designed by the state design bureau Pivdenne in 2015 after Ukraine lost touch with another satellite, Sich 2. According to Taftay, the previous satellite broke down because it was made of low-quality components imported from Russia. The new satellite, however, will be all-Ukrainian, he said.

Compared to modern satellites, Sich 2–30 is outdated, Usov said. It was designed to go into space with the Ukrainian rocket Dnipro, not Falcon 9, meaning that Ukraine had to adjust it. It is also larger and less technologically advanced than the new generation of satellites.

“But given that Ukraine does not have its own satellite, it is a big step forward,” Usov said