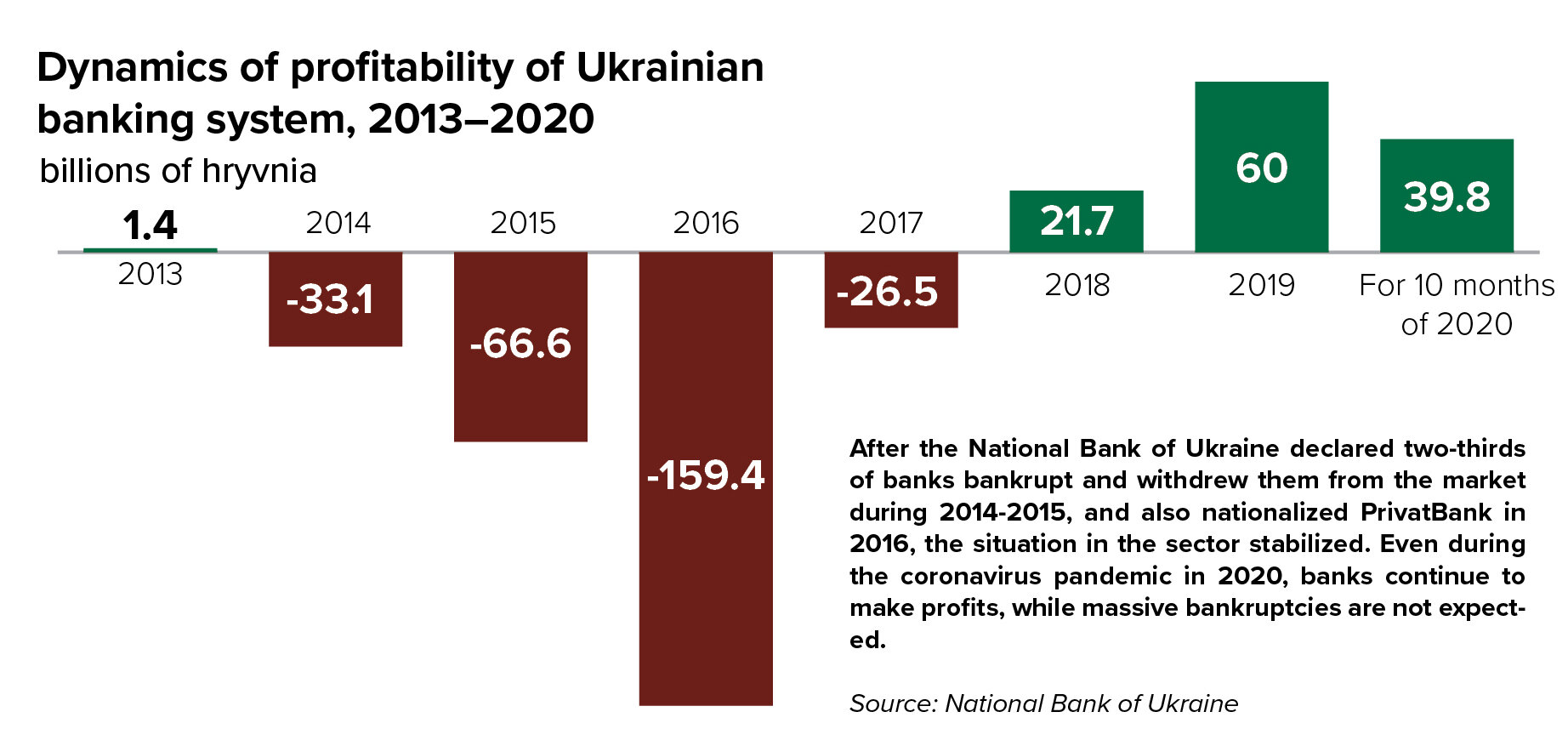

A severe economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic could have brought Ukraine’s banking system to its knees.

But that didn’t happen. It remained stable, proving that the country’s five-year cleanup of the banking sector, which eliminated nearly two-thirds of Ukraine’s banks for illicit schemes, was not in vain.

Despite a 23% drop in net profits by the end of October, 62 out of 74 operating banks in Ukraine remain profitable, according to Olena Korobkova, executive director at the Independent Association of Banks of Ukraine.

Altogether they earned $1.45 billion, demonstrating a slow recovery this fall.

“This is the first time for our country that an economic crisis does not go hand in hand with a financial one,” said Kateryna Rozhkova, first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during the Banking Forum on Oct.15.

During the financial crisis following the EuroMaidan Revolution and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, the country’s banking sector experienced a serious shock, provoking dozens of bankruptcies.

It was far worse than what European and U.S. banks are experiencing at the moment, according to Yulia Kyrpa, head of banking and finance at Aequo law firm.

After so many banks were removed from the Ukrainian market, strict requirements for financial monitoring were introduced. That proved extremely helpful during the pandemic.

As a result, “there was no mass hysteria and depositors did not rush to withdraw their funds,” said Gabriel Aslanian, a banking legal adviser at the Asters law firm.

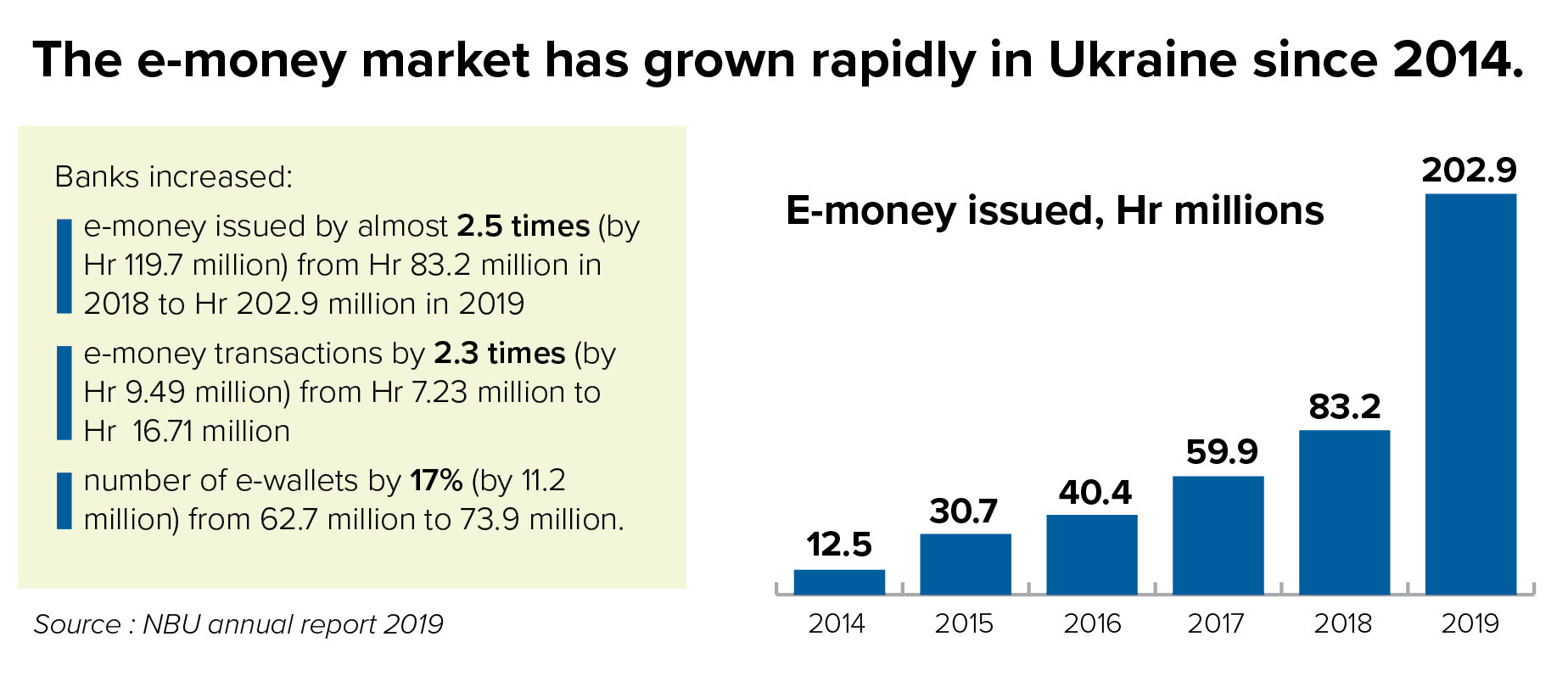

Moreover, the quarantine forced many Ukrainian banks to invest in online technologies to be able to serve customers online.

“In the first months of quarantine, banks were forced to go through the path of digital modernization, which was previously planned for several years in the future,” said Korobkova.

According to financial analyst Ruslan Cherniy, it will help them to be competitive on the financial market — for example, when, in a few years, companies like Amazon with their own payment systems enter Ukraine and partially replace banking services.

“This quarantine will help Ukrainian banks to survive in the future,” he said.

So what risks are there for the banks? Experts say that, should the government impose another lengthy quarantine, stripping Ukraine of 15–20% of gross domestic product, the banking sector will be heavily harmed.

Key trends

As the National Bank of Ukraine decreased its prime rate to a historic low of 6% this summer, banks also decreased their interest rates to the record 9%.

“The era of high interest rates has ended, and we need to look for other tools to work further and maintain efficiency, including optimizing processes in the banking sector,” said Rozhkova.

Surprisingly, the rate change did not provoke any outflow of deposits from banks.

Moreover, the inflow of deposits grew by 27% in the national currency and by 5% in foreign currencies for the first nine months of the year, central bank governor Kyrylo Shevchenko reported during a briefing on Oct. 23.

Due to quarantine measures and significantly reduced incomes among Ukrainian citizens, the growth of consumer loans decreased threefold to 9% as of October. But experts see the lack of corporate lending as a much bigger problem.

“For many banks, the risks for lending to businesses are still very high compared to the profits that they can bring in,” said Ihor Olekhov, head of the banking and finance practice at the CMS law firm.

“In order to lend to a business, there should be a project and a borrower with a good reputation. It is difficult to find new ones,” said Kyrpa.

First Deputy Governor of the National Bank of Ukraine Kateryna Rozhkova speaks with the Kyiv Post on Sept. 21, 2020. Rozhkova and Dmytro Sologub, the other central bank veteran who served under governors Yakiv Smolii and Valeria Gontareva, were repri- manded in late October for talking to the media, including to the Kyiv Post, under new governor Kyrylo Shevchenko. The incident was a troubling indicator to some in the West and in the business community that political pressures are eroding the central bank’s independence. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

There are also historical reasons for Ukrainian banks’ weak desire to lend. Until last year, the government had never adopted a law on creditors’ rights.

“Lawmakers and their inner circle had giant loan portfolios in banks for their corporations,” said Cherniy. “This situation just killed any desire of banks to work in the real sector.”

Nevertheless, during the pandemic some banks slowly started lending to small and medium businesses. In parallel, the government launched its program of affordable loans for these businesses.

It was intended to compensate for the interest on already-issued loans, but could not amount to more than 200,000 euros for three years.

According to Ruslan Hashev, former executive director at the Business Development Fund, more than 20 banks in Ukraine participated in this program and issued loans totaling $185 million for nearly 5,000 entrepreneurs.

“With this program, we significantly reduced risks for the banking sector from the growth of nonperforming loans in their portfolio,” said Hashev.

Digitalization became another tendency on the market. It led many banks in Ukraine to start closing branches and firing workers. Overall, almost 2,000 employees were dismissed and 500 branches were closed across the country, according to the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine.

“Closing branches is a normal trend and there is nothing wrong with that,” said Kyrpa. “Banks do not need so many.”

During the lockdown, it became clear that so-called neo-banks and fin-tech companies, which do not have physical branches and operate have much lower tariffs for their services, may become real alternatives on the financial market.

“It’s a global tendency,” said Kyrpa.

New bankruptcies?

Since the beginning of the year, only one Ukrainian bank — Arkada — was declared insolvent by the National Bank of Ukraine. But all experts agreed that this was not due to the pandemic, but due to its business model focused exclusively on construction.

Kyrpa does not expect any other bankruptcies in the near future. But other experts are not so sure.

Cherniy forecasts that some will leave the market next year if their shareholders don’t know how to run their business in the current conditions or don’t want to invest in the banks’ capital.

“I think it may be seven to 10 banks for sure,” he said.

According to Korobkova, the economic crisis may push shareholders in several Ukrainian banks to just leave the market.

Moreover, after the NBU did its stress test this summer, it turned out that the government needed to pour money into the nine weakest banks. Two of them are state owned — Oschadbank and Ukreximbank.

The latter bank had the largest losses, $80 million, in the Ukrainian banking system by the end of July 2020.

Most likely, the government will support the state banks. Private banks are still an open question.

“If they won’t receive additional capitalization, then the consequences may be sad (for them),” said Aslanian.

State banks vs. market

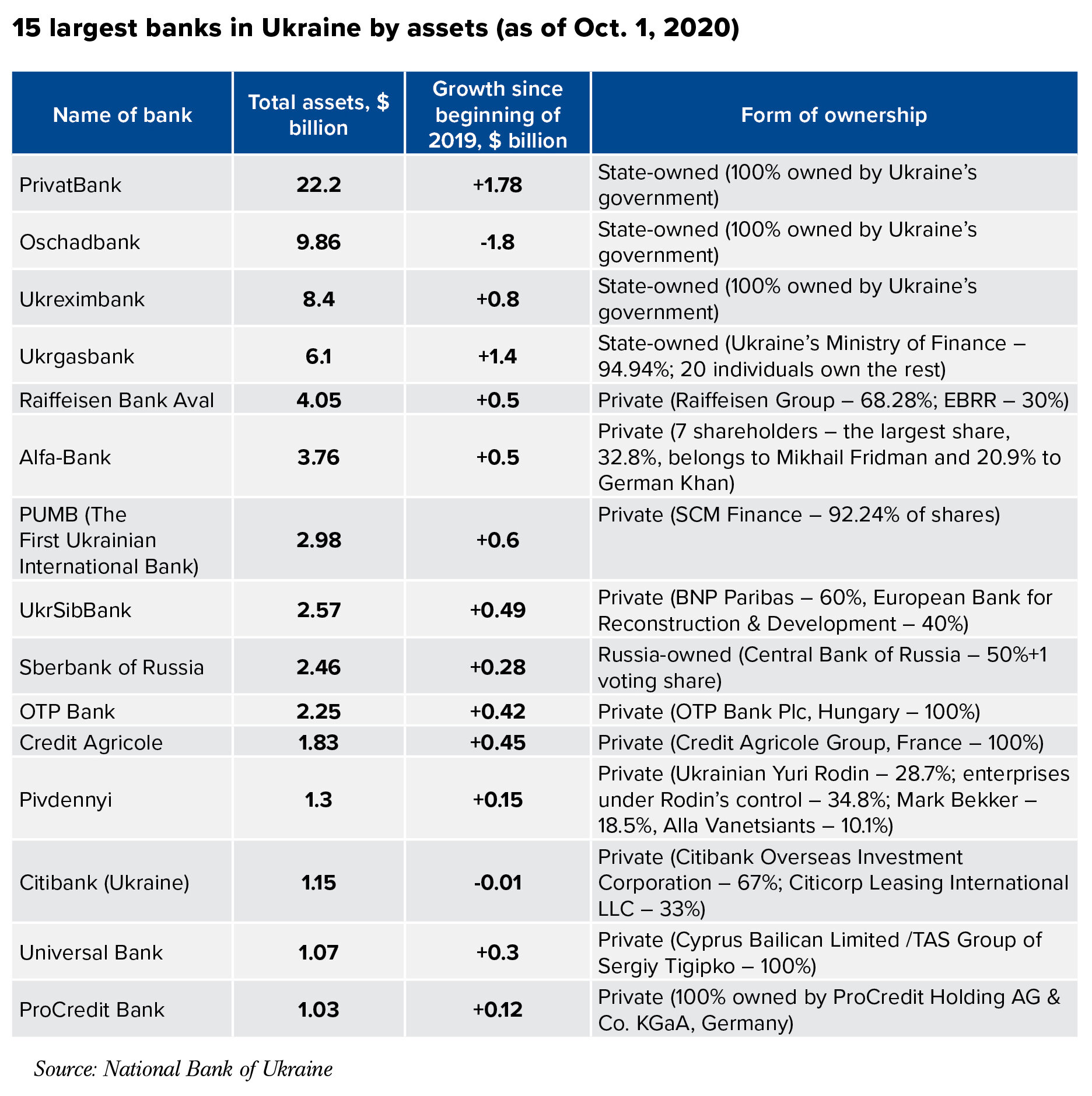

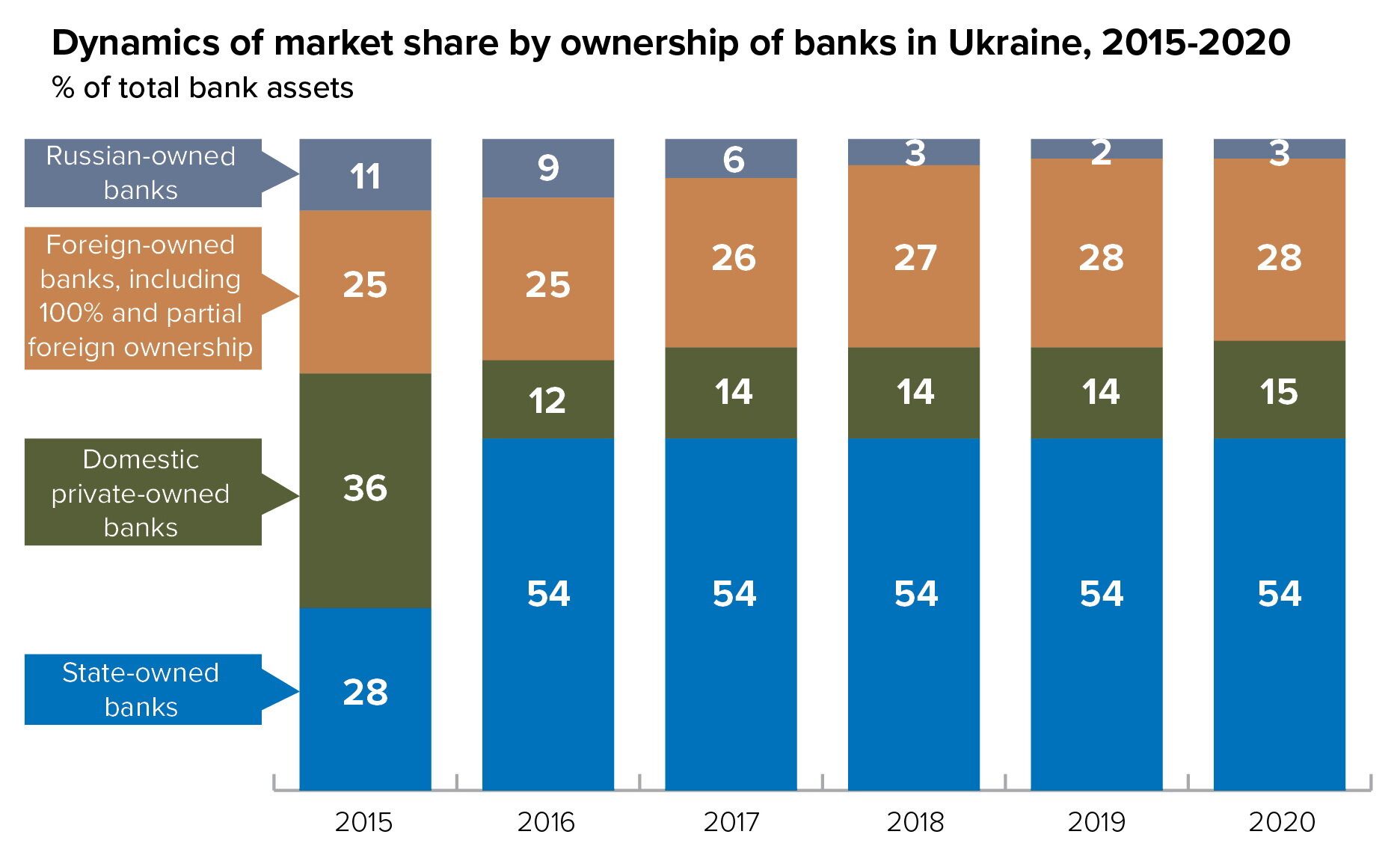

In the European Union, the state’s share in the banking sector does not exceed 10–15%. But in Ukraine, four state owned banks — PrivatBank, Oschadbank, Ukrgazbank and Ukreximbank — make up over 54% of the sector.

That came about due to the nationalization of the country’s largest bank, PrivatBank, in 2016, which “saved the country’s financial system from an immense shock,” Korobkova said.

But that huge state presence negatively affects competition on the market.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic the process of banks’ privatization planned by the government has slowed down.

According to Shevchenko, partial privatization of Ukraine’s state-owned banks will begin no later than in the next four years. Only Ukreximbank, which focuses on international trade and payments, should remain in the state’s ownership, the experts agreed unanimously.

“Everything else — it’s private business,” said Olekhov. “If the NBU will work properly and will regulate private banks in the right way, we won’t need state-owned banks.”

Source: Berlin Economics consultancy

Hashev agreed, calling such a large share of state banks “not normal.” It is one reason foreign banks don’t want to enter the country, he added.

“Why would they enter if we don’t have enough competition and the state can influence the whole market?” said Hashev.

Too risky to enter Ukraine

Almost 30% of banks operating in Ukraine are foreign, but, for the past five years, not a single new one has entered the country’s market.

“It’s a sign that we have a problem in this sector,” said Olekhov.

Those foreign banks that already operate in Ukraine entered the country many years ago, and “still believe in some prospects for the Ukrainian market.”

But while other countries, like Turkey, can boast plenty of European, American and Asian players in the banking sector, “Ukraine is not on the map for those banks,” Olekhov said.

Among key issues obstacles are problems with the Ukrainian judicial and law enforcement systems, and a toxic business climate. “The cost of doing such business in Ukraine is too high for them,” he said.

Recent rulings by the Constitutional Court, which undermined the country’s anti-corruption institutions, adds more risks for foreign investors in the banking sector, experts said.

“The decisions adopted there may have a very serious impact on what will happen in the country,” said Aslanian.