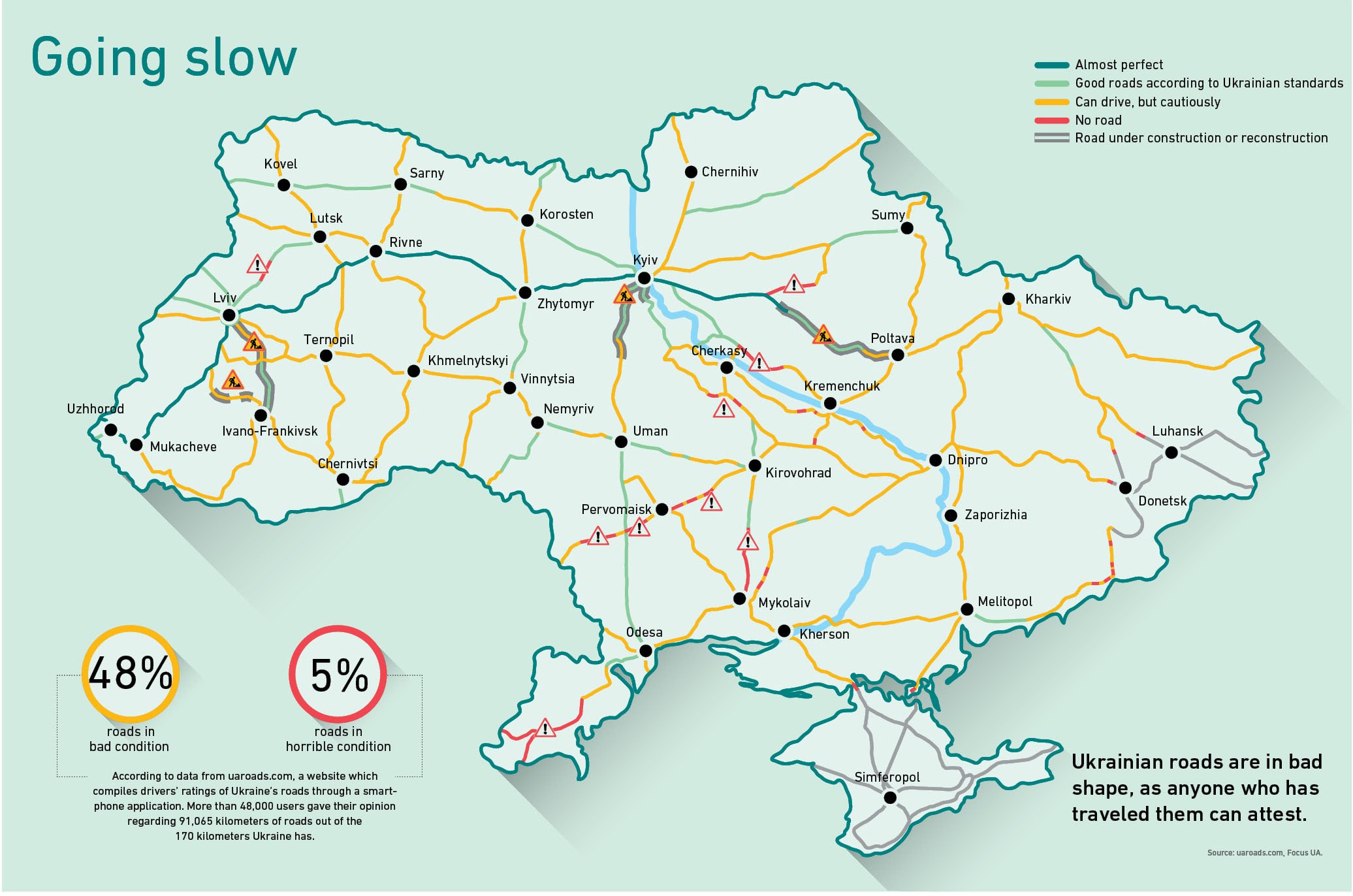

When people complain that Ukraine's roads are all bad, they are almost right – just 3 percent of the nation's roads are in a satisfactory condition.

Ukravtodor, the country’s state-owned road repair company, is ineffective and corrupt. Its sole achievement has been to keep the main routes between major cities in passable shape.

Despite hundreds of millions of dollars in grants from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank being allocated to the country’s roads, they continue to deteriorate. This makes it hard for commerce, expensive for drviers and deters social cohesion in general.

A trip from Kyiv to Lviv, roughly 540 kilometers, takes around eight hours. A trip of about the same distance in the United States, say from Chicago to Cleveland, would take a little over five hours.

Since early 2015, the Infrastructure Ministry has been lobbying for overhauling Ukravtodor. Under the ministry’s plans, the company would be only responsible for managing the country’s main highways, while independent local road departments would maintain the regional roads. Local governments are responsible for the roads within the cities.

But such changes have not yet found the support in parliament.

Ukravtodor didn’t reply to requests for comment on this story.

‘Marshall Plan’ for roads

When Roman Khmil, an information-technology executive, joined the Infrastructure Ministry as the deputy of then-Minister Andriy Pivovarskiy in March 2015, fixing the roads was his top priority.

He trumpeted a Hr 1 trillion ($40 billion) “Marshall Plan” for Ukraine’s roads that would decentralize Ukravtodor, devote resources to maintaining the country’s main freight transport roadways, and impose weight restrictions on trucks to stop them from degrading the roads.

But Khmil resigned in April, with almost none of the goals accomplished.

“We drafted the legislation that was required,” Khmil said, summing up his achievements.

But parliament passed none of the laws that Khmil and the infrastructure ministry submitted, including a proposed slush fund for road maintenance and a bill to decentralize Ukravtodor.

Apart from parliament’s failure to pass legislation, personnel issues hobbled Khmil’s attempts.

Khmil and Pivovarskiy spent months attempting to oust former Ukravtodor chief Serhiy Pidhainy, who had led the organization since June 2014. The ministry team finally managed to install the current head, Andriy Batischev, in October 2015.

But in December Batischev was attacked and beaten up in his own office – allegedly by employees of a Mykolayiv contractor whose services he had turned down.

Tender problems

However, even with proper management, there is little money available to properly fund road construction.

Much of Ukravtodor’s budget comes in the form of grants from foreign lenders like the European Bank for Regional Development and the World Bank, who pay for maintenance of the largest highways.

But Ukravtodor has been consistently accused of corruption in tenders, raising questions of how effectively the donor money is being used.

The problem appears to be rooted in Ukrdorinvest, the division of the organization that handles foreign funding. One engineer who works on Ukravtodor contracts told Kyiv Post that the investment division’s office “looks like Goldman Sachs.” He would not give his name as he wasn’t authorized to speak to the press.

Kyiv Post requested comments from Ukravtodor on its investment division’s work. The company didn’t respond.

Oleg Ostroverkhiy, ex-chief engineer for the Kyiv Road Administration and a consultant to the Ministry of Infrastructure, said that Ukrdorinvest began to siphon off increasingly more money around 2010, when ex-President Viktor Yanukovych came to power.

“Then everything began to get worse and worse and worse – there was more pressure on the bosses,” Ostroverkhiy said.

One example is Ukravtodor’s deal with Spanish road maintenance firm Elsamex. The company won a tender in January 2014 to maintain the Kyiv-Chop highway for seven years on an EBRD-funded contract, having offered the lowest bid – $50 million, beating Turkish firm Onur, which bid $61 million.

But by August 2014, the Elsamex deal was off. Ukravtodor cancelled the firm’s contract, saying that the company had failed to maintain the road, and hired Onur instead.

“What happens now is that this contractor goes and tells other foreign contractors, ‘don’t go there,’” Ostroverkhiy said. “They can throw you out, trick you, etc.”

Deadly consequences

The low standards in Ukrainian road building and maintenance can have fatal consequences, as seen on the Kyiv-Chop M06 highway.

Renovated in 2009, the highway was remade without a key feature: overpasses for drivers that need to either make a left turn or a U-turn. To make such a turn on the highway, which passes through Lviv to the border with Hungary, drivers instead have to turn into oncoming traffic.

“The death rate almost tripled,” said Khmil. “They designed holes in the barriers so cars could do U-turns, and there are head-on collisions.”

Ostroverkhiy also said the traffic mix of high-speed modern cars and slower Soviet models also make the roads more dangerous.

“Speed is the main cause of death on Ukrainian roads,” Ostroverkhiy said.

Truck lobby trounced?

However, Ukravtodor in May won a crucial battle against the country’s influential truck lobby.

Ukraine’s roads have been worn down by overloaded trucks that place more weight on the roads than they were originally designed for.

The problem has been exacerbated by Russia’s annexation of Crimea, which forced trucks that would have otherwise gone to the port of Sevastopol to deliver freight to the port of Odesa, degrading the roads in Odesa Oblast. Additionally, a law passed immediately after the EuroMaidan Revolution that lifted weight requirements on trucks in an effort to stimulate commerce is still in place.

“It’s a fight with business,” Khmil said. “They got used to saving money by carrying goods two or three times overweight. While they save $1,000, they cause 10 times more damage to the roads.”

The dispute peaked on May 14, when truckers blocked the Odesa-Kyiv highway after the Ministry of Infrastructure installed a new weigh station to try to stop overloaded trucks from traveling.

All the truckers “knew their vehicles were overweight,” Khmil said.

But thanks to the intervention of Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman, who said in a statement that “overweight vehicles must not destroy Ukrainian roads,” the protest failed. According to Khmil, trucks along the Kyiv-Odesa highway now appear to be driving within the weight restrictions.

“The truck owners realized that the government was serious,” Khmil said.

$40 billion needed

Despite that victory, Khmil still doubts that the cash-strapped government can find the funds needed to bring Ukraine’s roads up to scratch.

As of today, Khmil said, it would cost more than Hr 1 trillion ($40 billion) over the next decade to repair Ukraine’s road network. He adds that on top of that, an additional Hr 50 billion ($2 billion) is required annually just to maintain the roads in their current condition.

“Those who are scared by this can pack their suitcases,” Khmil wrote in a Facebook post, “and go to countries whose citizens at some point ‘got off the couch’ and made a meaningful effort to create the quality of living and the development of society that we see there.”