Asked to name a single cultural trait he admired in Ukrainians, Swedish Ambassador to Ukraine Tobias Thyberg came up with “resilience.”

And for his country, one of Ukraine’s most important European partners, it’s “optimism.”

Combine the two traits, and you’ve got something there.

In a way, that’s the challenge facing Ukraine — to stay resilient and optimistic as the nation keeps fending off Russia’s aggression, now for more than six years, while simultaneously trying to tackle corruption and build rule of law, respect for human rights and democratic institutions.

Sweden sees the issues as inextricably linked and, really, one and the same.

“I do hope and believe that Ukrainians understand that we have their back” in meeting this challenge, Thyberg said in an interview with the Kyiv Post on Aug. 12 in his official residence.

Thyberg, a gay man married for two years to his longtime partner, German Florian Fuckner, has been the ambassador of Sweden to Ukraine since September. He comes by way of Afghanistan, his first ambassadorship, where he would have gladly stayed beyond his two-year contract if possible.

Thus far, in his 44 years of life, he found Afghanistan to be one of the most exhilarating and emotional experiences of his life. Amid the death and carnage, he said, it was also a lot of fun — and he left with great admiration for Afghans.

“When you’re in a place like that, it seems extremely real and every single conversation you have becomes about existential stuff,” Thyberg said. “I didn’t really know what to expect. I found a country that is anything but provincial or peripheral or anything but distant. When you’re there, you feel like you are in the middle of the world… I really love the country.”

But when it came time to leave, he got the posting he wanted — to Kyiv.

Ukraine represents a natural trajectory of his training that began in his teenage years, when he joined the military service and studied Russian for 15 months. His other postings include to Russia and to Georgia, where — like in Ukraine and Russia — Russian-language fluency comes in handy. He’s also been stationed in India, the United States and Belgium.

He finds Ukraine a fascinating place to be, although COVID‑19 has “thrown a wet blanket over travel in the country” and his ability to lead a staff that can physically work in the same location — the embassy on 34/33 Ivana Franka St.

“Ukraine is clearly not a country at peace,” he said. “I feel there is so much going on politically in Ukraine every day. This is a country where institutions are being built, tectonic plates are shifting. There is a fundamental competition over what will be the nature of this state, how is power to be distributed? Ukraine does not seem calm in any way. It’s extremely exciting.”

A view of the Swedish parliament on May 14, 2020. On the foreign policy side, Sweden strongly supports sanctions against the Kremlin for its annexation of Ukrainian Crimea and war in the eastern Donbas. (Ulf Grünbaum/Imagebank.sweden.s)

Why Ukraine matters

While it is almost pro forma that every ambassador stationed in Kyiv declares Ukraine to be vitally important to the country he or she represents, Sweden offers more proof than most other nations to back up Thyberg’s statement that “Ukraine is hugely important for Sweden.”

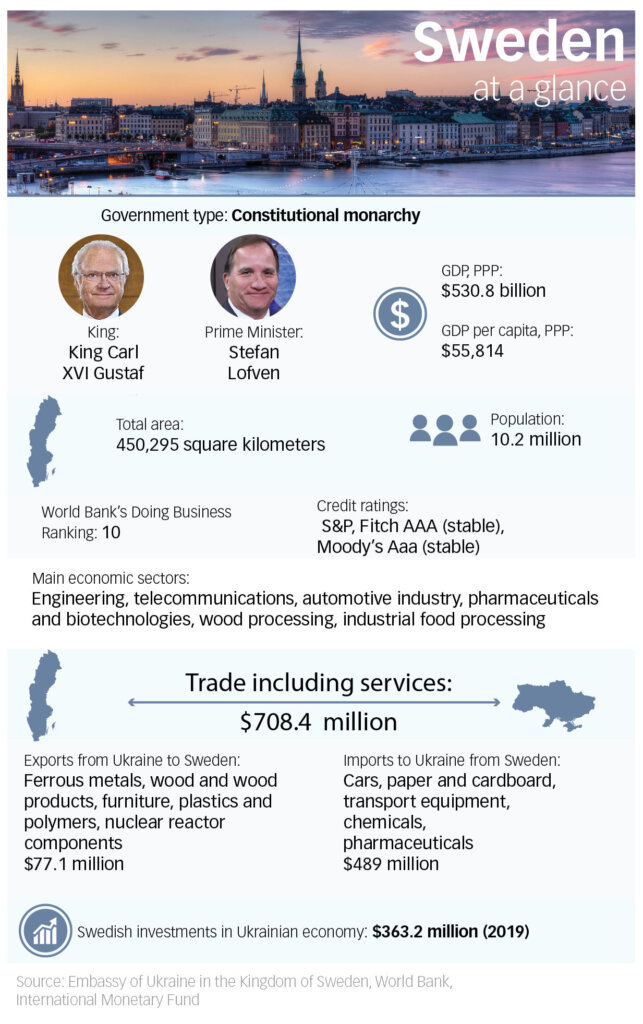

First off, the wealthy Scandinavian nation of 10 million people is one of the few in the world that commits 1% of its gross domestic product to foreign development assistance. For Ukraine, this has meant 30 million euros a year in bilateral assistance from the Swedish government channeled through the Swedish International Development Corporation, or SIDA, an agency of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Sweden takes the long view on foreign assistance, and is set to devise a new seven-year budget for SIDA through 2027, which will likely include comparable amounts of annual aid to Ukraine, unless COVID‑19 forces government budget cuts.

The money goes to support three main areas: economic development; environment and energy; and the promotion of democracy, human rights and gender equality.

Included in the promotion of democracy is support for independent media in Ukraine. The recipients in the current cycle of funding include support for public television, including Hromadske TV, and for Detector Media, a media watchdog.

On the foreign policy side, Sweden strongly supports sanctions against the Kremlin for its annexation of Crimea and war in the eastern Donbas. As a member of the European Union but not NATO, Sweden also participates in helping to train Ukraine’s army through such programs as the Canadian-led Operation UNIFIER in western Ukraine. It does not, however, provide Ukraine with lethal weapons, but is looking to expand naval cooperation.

“It’s more than sympathy,” Thyberg said, explaining why Sweden is helping to build Ukraine’s defense forces. “Sweden looks at what is happening and it’s awful. If the European security order regarding the inviolability of borders and state sovereignty can be swept aside (by the Kremlin) in Georgia and then in Ukraine… I am not saying that Sweden is going to be the object of Russian aggression the day after tomorrow. But (Russian aggression) is a direction of travel we’re very uncomfortable with.”

High-level visits

Another sign of Ukraine’s importance to Sweden is the frequency of high-level visits — the prime minister, foreign minister and defense minister have all made trips to Kyiv in the last year or so.

But amid the pleasantries and tangible support, Sweden manages to deliver a tough-love message in its own way, encouraging Ukraine to develop rule of law, fight corruption and establish trustworthy courts — for its own good.

“These are intimately linked issues,” Thyberg said of Ukraine’s challenges of defeating Russian aggression while fighting corruption. “Over time, the extent to which Ukraine will be able to defend its sovereignty and its territorial integrity will relate in no small part to the extent that it is able to create a strong democracy, rule of law and human rights in the country.”

What business wants

Both sides believe that annual bilateral trade is nowhere near its potential, hitting perhaps $700 million last year. But trade has grown at a brisk pace between Sweden and Ukraine since the economic crash of 2014 — it’s more than doubled. Ukraine is home to only 1,000 or so Swedes, but Ukraine hosts about 90 Swedish businesses, including in agriculture, energy, and tech industries.

“That tells me this is a remarkably broad and big market with a lot of human capital,” Thyberg said. “There’s a wide range of opportunities for Swedish businesses in Ukraine.”

Of course, IKEA’s opening of an online store in June “after having spent years trying to figure out” how to enter the Ukrainian market was a major step forward. Demand for IKEA’s famous home furnishings was so high that its website crashed in the first 24 hours.

But at a reception of Swedish business representatives, he was told the same story about what Ukraine needs to attract more foreign investment, including Swedish: rule of law.

“I got the same exact answer from every single one. They have to get rule of law to work in this country. It’s the one thing which is so much more important than everything else,” he says.

“They said: ‘We need courts that are impartial and effective and make decisions and can’t be bought. We need government agencies that have the muscle to enforce those decisions so it doesn’t end up being a piece of paper that the judge signs and it means nothing at the end of day. We need to not be shaken down (for bribes) or have black-windowed SUVs drive up with automatic guns in grain fields in the agricultural part of the country, (with thugs inside) saying these 150 hectares you are farming are not yours anymore.”

Ukraine’s advantages

In this epic struggle to shed its Soviet legacy, Thyberg draws on his three years in Moscow — from 2005 to 2008 — to sound an optimistic note about Ukraine’s prospects.

According to him, the differences stand out more than similarities — the differences in political culture, freedom of expression, pluralism, and freedom of the media.

“Back in 1991, Russia and Ukraine chose two fundamentally different paths,” Thyberg said. “There is a whole generation of Ukrainians in public administration, in business, in academia and in civil society” who have created “a fundamentally different” country than the one led by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“I have been struck by how much of what I have experienced in Ukraine is not like Russia,” he said.