Two protests last week were like nothing that Ukraine’s government has ever seen before.

Hundreds of people danced to techno music by the Cabinet of Ministers building with top DJs spinning records on Sept. 1. Two days later, the government headquarters were artistically besieged by Ukrainian musicians – both famous and lesser-known.

The two groups had usually been uninterested in politics, but this time they came out to protest against a decision that affects their livelihoods directly – the government’s COVID-19 quarantine restrictions. Though the constraints are becoming stricter, the government is not providing any financial aid to the entertainment industry.

“It’s not about making money now,” nightclub owner Evgeniy Jay Fokin told the Kyiv Post. “It’s simply about survival.”

Months of restrictions

The Ukrainian entertainment industry has been on a rollercoaster of quarantine restrictions for months.

First, during the beginning of the quarantine, the government cut its funding for music festivals and other cultural events from the state budget.

The government then forced all restaurants – including nightclubs and music venues – to close on March 17 and banned mass events. Almost three months later, it allowed restaurants to reopen summer terraces on May 11.

Then it got complicated. The government introduced its “adaptive quarantine” plan that allowed restaurants to cautiously reopen indoors on June 3, but not in regions with high infection rates. Mass events were still banned, but nightclubs started to reopen since most of them are registered as “restaurants” in Ukraine.

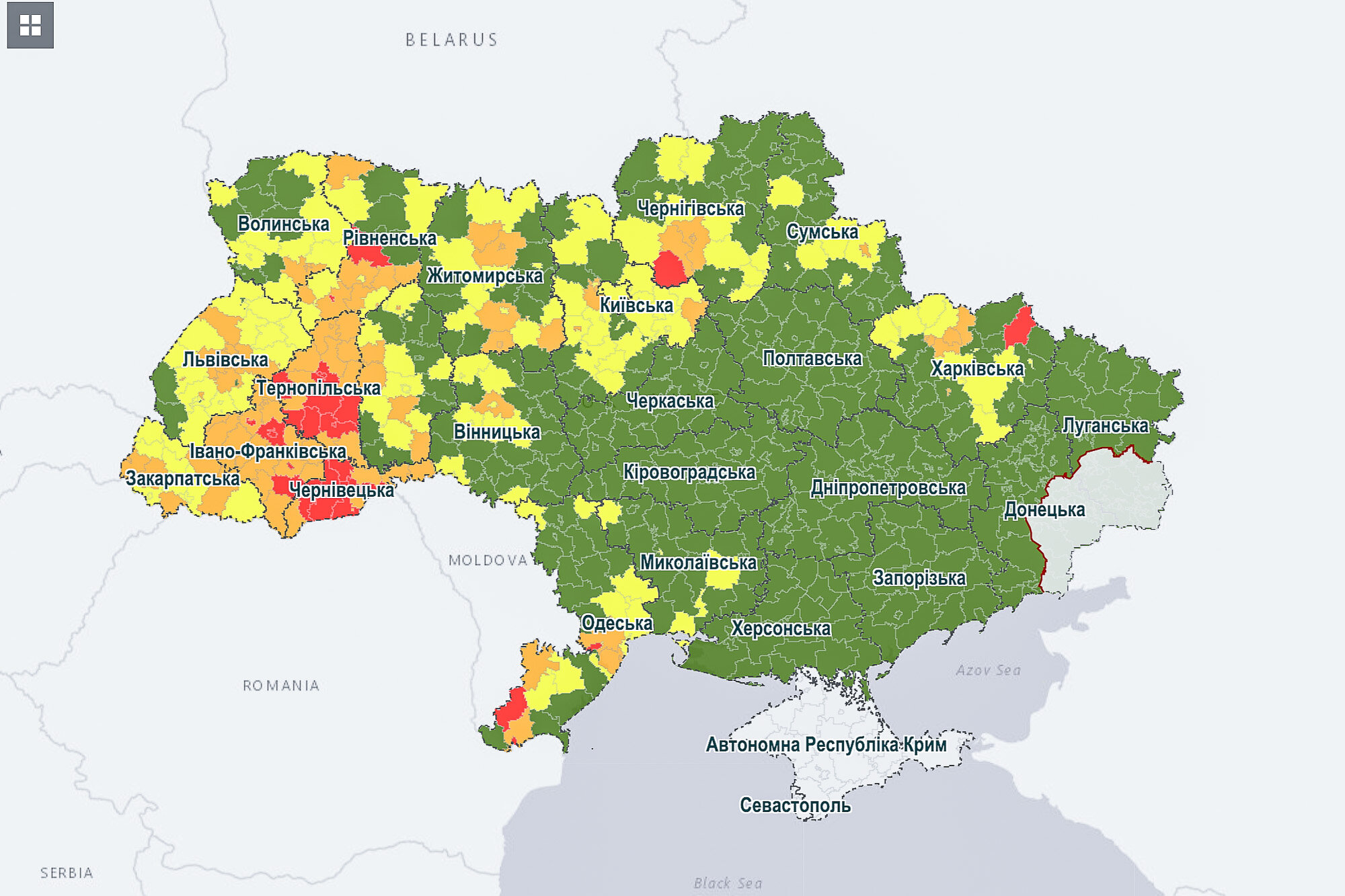

Then it got even more complicated. In August, the government started dividing communities, rather than regions, into green, yellow, orange and red zones representing the severity of COVID-19 spread. In the green and yellow zones (the less affected zones), the state allowed public events. But these events could hardly be called mass gatherings, as the government required that there be no more than one person per five square-meters of a venue’s space.

In the orange and red zones, the government allowed public events with no more than one person per 20 square meters. But it also banned restaurants in orange zones from working during the night and in red zones from working altogether.

That’s how things stood before Aug. 26, when the government extended the quarantine until Oct. 31 and did something that finally made the entertainment industry protest.

Ukraine’s COVID-10 threat levels that come into force on Sept. 7, 2020. (Public Health Center of Ukraine)

No nights for nightclubs

In a meeting on Aug. 26, the government decided to ban entertainment venues like nightclubs from working after midnight in all but green zones. Currently, this applies to nightclubs in Ukraine’s three largest cities – Kyiv, Kharkiv and Odesa — and in most western Ukrainian cities.

Night clubs played a significant role in the spread of COVID-19 in western Ukraine, according to a government source, who was not authorized to speak to the media on the record.

“We all know and see how certain entertainment venues work today, nightclubs in particular – absolutely without observing face mask requirements, without social distancing,” Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal said at a government meeting to justify the restrictions.

Kyiv’s nightclubs disagreed. They protested on Sept. 1.

In a joint statement, they accused the government of playing up their blame for the virus’ spread and said they have followed all the sanitary requirements. Further restrictions will lead to the industry’s decline and the unemployment of a large share of the population, they argued.

“Every venue and canceled event means thousands of jobs and countless related professions of people left without the means to live and support their families,” according to the joint statement by the nightclubs, which includes venues such as Closer, Otel, Chi, River Port and Skybar.

Fokin, the owner of the Fifty nightclub in Kyiv, says that he experienced the financial hit during the first three months of the quarantine. His savings dwindled as he had to pay rent and he couldn’t pay his employees. Most of them rent apartments, he says, so by June, their financial situation was critical.

That’s why they reopened when they got the chance after most restaurants were allowed to operate in June. Fokin says that his nightclub still admitted no more than one visitor per five square meters, so people spent less money inside. Still, it was a way to stay afloat.

But now the club can work only until midnight. In addition, even fewer visitors are allowed inside simultaneously because the government imposed a stricter limit for the number of people at public events in the yellow zone — only one person per 10 square meters.

Meanwhile, the government does not provide any financial aid to nightclubs, unlike other European countries that do, the owners argue. Other than allowing them to work at nighttime with more visitors, the nightclubs demand some assistance or tax cuts from the government. Nightclub owners also want their representatives to be in the room when the government makes decisions about entertainment industry restrictions.

“We will protest until we are heard. What choice do we have?” Fokin says.

Music artist Maksym Sikalenko, known by his stage name Cape Cod, protests in front of the government’s headquarters with a sign that translates to “They Don’t Hear Us” in Kyiv on Sept. 3, 2020. Sikalenko, like other protesting artists and members of the All-Ukrainian Trade Union of Music Industry), demanded that the government allow all organizers to hold music events and develop a plan to save the music industry from the affects of the COVID-19 quarantine. (Facebook / Ukrainian Music Trade Union)

No venues for artists

Another move by the government on Aug. 26 provoked the first-ever protest of the All-Ukrainian Trade Union of Music Industry. In fact, music artists, producers, promoters and journalists created the union partly in reaction to the quarantine restrictions in June.

What finally angered them was the government’s decision to ban all music shows and parties of organizers whose primary specialty is not “concert activity” as listed in their entrepreneur’s registration documents. This applies to all of Ukraine, even for communities in green zones.

This is discrimination against organizers based on a formality, artists such as Alina Pash, Alyona Alyona and Olya Polyakova argued as they joined the protests. Entrepreneurs in Ukraine usually have several types of activities listed in their registrations papers, and, too often, their main registered activity is rather random.

For artists, this means fewer places where they can perform. And without music shows, they lose most of their income, since, in Ukraine, artists make only a fraction of their money from record sales and streaming.

Music artist Maksym Sikalenko had to turn to writing music for commercials to make money. His indie electronic music project Cape Cod can’t bring much profit now, he says, and all of his shows in Ukraine, Germany and the Netherlands were canceled.

“Perhaps only the top-level artists, about 4%, continue to work. Many independent artists of the middle and lower levels are changing careers, trying to adapt and find a way out,” Sikalenko told the Kyiv Post.

Sikalenko himself became a board member of the union. The union plans to work with the government to develop the music industry, in particular by creating a royalty payment system for artists similar to those in Europe. In the meantime, however, they are trying to at least set up a dialogue to put out the fires caused by the quarantine.

“And there’s not much dialogue yet,” Sikalenko says. “That’s why we demanded that the prime minister develop a clear plan to get out of this funk.”