Author Andrey Kurkov was not planning to write about Russia’s war in Donbas.

He is considered one of Ukraine’s most successful post-Soviet authors, who spent 20 years trying to dissect Ukraine and understand the influence of the Soviet past on the country’s post-Soviet people.

Kurkov looks back at history to understand what came to be, something that is not possible to do with an ongoing war.

“How can we write about the war that is still not finished?” Kurkov told the Kyiv Post.

But after Kurkov traveled to the Donbas, what he witnessed pushed him to change his mind and write “Grey Bees,” a novel about Russia’s war in eastern Ukraine and occupation of Crimea and how they affect the daily lives of locals.

Despite the fact the war in Donbas has not ended, many detailed books, essays, and theses have been published about it by soldiers, journalists, activists and regular citizens. But the majority of this content has been documentary. “Grey Bees” is one of the few pieces that are entirely fiction.

The book was published in Russian in 2018 but was recently translated into English. The English version is now available on Amazon for $11–22 and in bookstores across the United Kingdom, Norway, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, Ireland, Italy, France and Germany.

The first half of “Grey Bees” has also been recently transformed into a play in Ukrainian that will premiere at Kyiv’s Theater on Podil on Jan. 29, with repeating performances scheduled for Feb. 23 and 24.

Grey zone

Since the winter of 2015, Kurkov had journeyed three times through the Donbas along with his friend who made trips to the region to bring supplies to the locals. There, the author witnessed how people were living in the so-called grey zone, between the Ukrainian and Russian-led forces, that runs along the entire 450 km long line of contact.

Instead of constant fear of danger on its doorstep, he saw the population’s apathy. War became the norm. People were ignoring it, treating it like a rowdy, drunk neighbor.

“These people are not political. Their life is not nice, but they are used to this life, and consider it stable,” Kurkov says. “They don’t want to live worse than this, and they don’t dream of living any better.”

The author endows his main character, Sergey Sergeyevich, with this attitude. The novel is set in the fictional grey zone town of Little Starhorodivka.

Sergey Sergeyevich, or just Sergeyich, is a simple man, a beekeeper and an introvert who finds comfort in his solitary routine. He wakes up, waits in bed until he can find the energy to get up and retrieve more coal for warmth, lies a bit longer in the heat, makes some tea with the minimal resources he has left and thinks about his bees.

“He sort of envies bees,” Kurkov says. “But at the same time (he) cares about them and subconsciously uses them as some kind of escape.”

He’s one of two residents left in town. The other one is his — “vrazhenyatko” — lifelong frenemy Pashka, who lives two streets over.

The frenemy relationship that the two have is quite entertaining to follow. Their “friendship” has become dependent, and as inescapable as the war surrounding their town. There is no way out, so the two of them must communicate. After all, only one of them can bury the other if someone is killed. Yet this fatalistic relationship based on necessity shows its moments of warmth and something more than forced solitude. The two old men seem constantly bothered and annoyed by one another, yet worry when they don’t see each other in a while.

Life in Little Starhorodivka is grey and monotonous, only to be interrupted by the deadly shelling and shooting between forces. The two residents live in a guessing game like battleship, wondering if the next shell will hit their house next. The war’s destruction has already taken the church, the main road and the houses of Sergeyich’s neighbors across the street.

Despite the looming danger, Sergeyich initially had no intention of moving. He could have joined his estranged wife and daughter who left years earlier for a town in central Ukraine but he didn’t.

“He accepts it. He lives four years without electricity and television,” Kurkov says. “He even accepts his eternal enemy as almost his friend.”

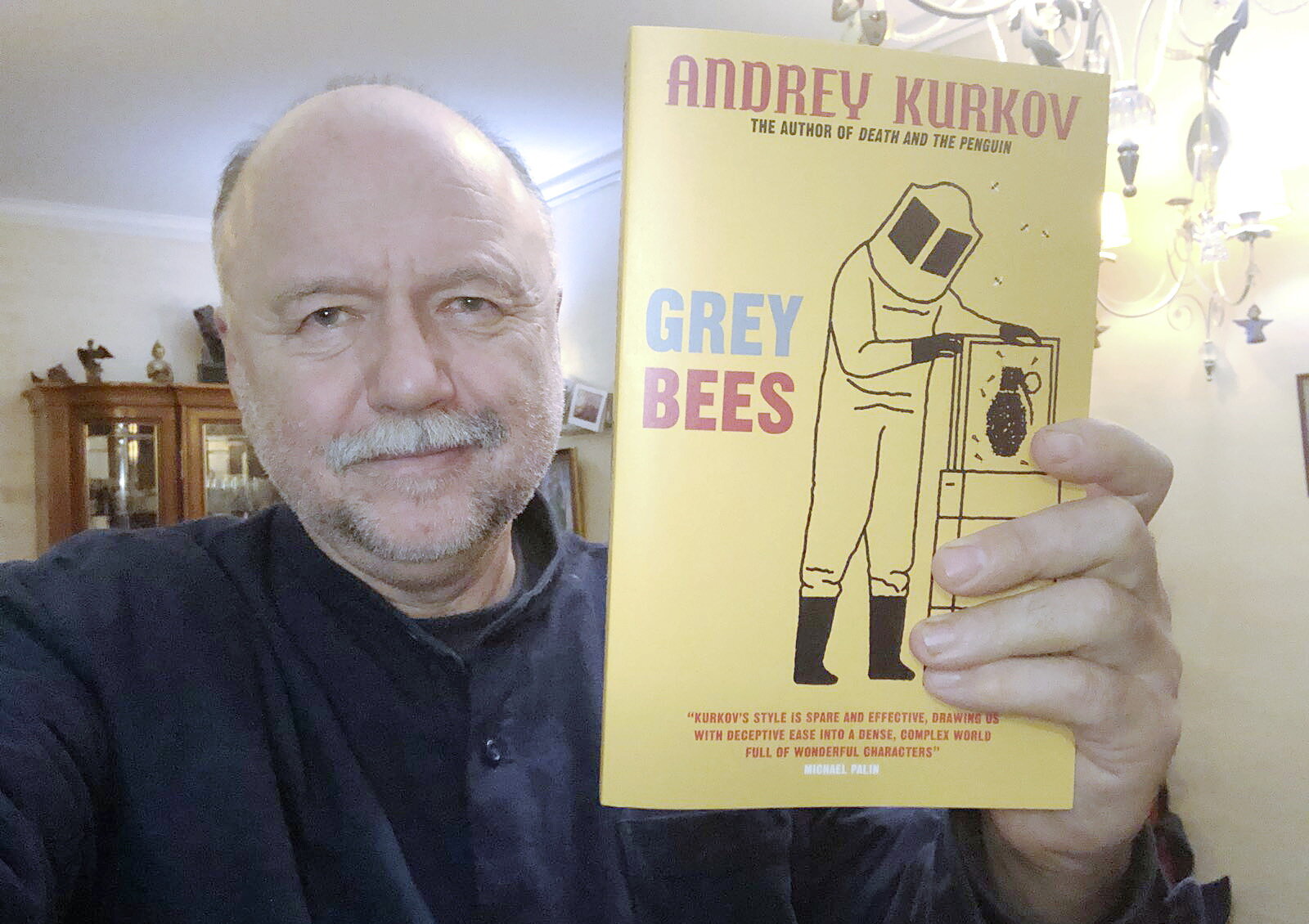

Russian-born Ukrainian author Andrey Kurkov poses for a selfie with the English version of his book “Grey Bees.” The novel follows the residents of the grey zone of Russia’s war in eastern Ukraine. (Courtesy)

The only factor that makes Sergeyich consider changing his routine are his precious bees. Winter will soon thaw, and he is afraid that the shelling will confuse the bees as they get back to work in spring.

So Sergeyich decides to move his bees to a calmer and warmer place. He eventually travels to Crimea in search of Akhtem, an old beekeeping friend. There, he and his bees again experience the consequences of Russian aggression, particularly the systemic persecution of Muslim Crimean Tatars.

Kurkov made sure to focus on what was going on in Crimea. Like many Ukrainians, he had spent most of his vacations on the peninsula. He would visit Crimea with family during his childhood when it was still part of the Soviet Union, and as an adult when it became part of Ukraine. Kurkov’s last visit was in January 2014, one month before the Russian invasion.

“The second half of this novel is, in some ways, my personal farewell to the Crimea that may never exist again,” Kurkov writes in the book’s foreword.

Ukrainian by choice

One of the largest divisions in modern Ukraine is the most basic answer to the question of what makes something Ukrainian.

The country is a beautiful mix of diversity. People in the west speak Ukrainian, some with Polish or Hungarian influence depending on the proximity to neighboring countries. Many of those in southern and eastern Ukraine spend their entire lives speaking Russian. Yet all are considered Ukrainian.

Sergeyich experiences his own complications of perceived identity in the book. He is from a Russian-speaking town in the grey zone and speaks Russian, but is Ukrainian. He chooses to be. But yet his Ukrainianness is questioned to the point that a Ukrainian soldier suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder chooses to break Sergeyich’s car and windows because he’s from the east.

Kurkov has experienced his own grey area of identity. He is considered to be one of Ukraine’s most successful authors, but he is in fact Russian-born. Having lived here since early childhood, he has chosen Ukraine to be his home. He speaks and writes in Russian, but his print books are banned in Russia because of his criticism of the Kremlin.

Since the start of the Donbas war, Ukraine has renationalized. The country got rid of Soviet names of streets and cities and started supporting the usage of the Ukrainian language in media, culture and most recently in the service industry.

Kurkov’s commentary on the politicization of language has been considered controversial in Ukraine. The author expressed the idea that Ukraine should make the Russian language its own cultural property, in part by setting up a Ukrainian institute for the Russian language.

“It would cut off our Slavists from the Russian Academy of Sciences and provide an instrument for the protection of the Ukrainian Russian language from Russian academics, who correct everything in their own way and decide what is right,” Kurkov said in a 2018 interview with Krym.Realii.

The author’s position has provoked a strong reaction from the Ukrainian nationalists for promoting “the Russian world.”

“Ukrainian” is a civic identity that isn’t based on language. When it comes down to it, it’s one huge grey area.

People both from the east and west are Ukrainian. Retirees that don’t receive a pension in the war zone are Ukrainian. Children born in the grey zone with no official birth certificates are Ukrainian. These people consider themselves to be Ukrainian, they choose to.

Though a story about war, “Grey Bees” does not focus on military operations and heroic soldiers, but on ordinary Ukrainians, to whom the war brought suffering or forced them from their homes.

Kurkov is powerless to predict when the war will end, but he hopes it leaves the residents of the grey zone alone — “that it goes away, and that the honey made by the bees of Donbas lose its bitter aftertaste of gunpowder.”