An American writer once said that good communication is as stimulating as black coffee, and makes it just as hard to sleep afterwards. If that were true for Ukraine, we would have to drink gallons of coffee to compensate for a diet with a deficit of communication. Ukrainians, for the most part, are reserved and tight-lipped during a first encounter.

They warm up when you get to know them better. Before that, however, don’t expect a shopkeeper to chit-chat, a waitress to serve you with a smile or even a press officer to speak nicely to you.

It’s frustrating to encounter indifference on the street, let alone manage daily interactions at work. Somehow introducing oneself as a journalist in this country doesn’t do the trick. Communications departments in Ukraine’s government institutions take all the time in the world to answer queries.

No one’s going to speak to you in the press office before you send them a fax, signed by the chief editor on letterhead. It must also carry a special number, assigned by the sender, so that civil servants can officially register it in their books – paper, not electronic, ledgers, of course. They don’t care if a journalist just takes this number from top of his or her head – it’s not their problem. I have learned to live with it as a silly procedure that helps you get someone on the phone within a couple of days.

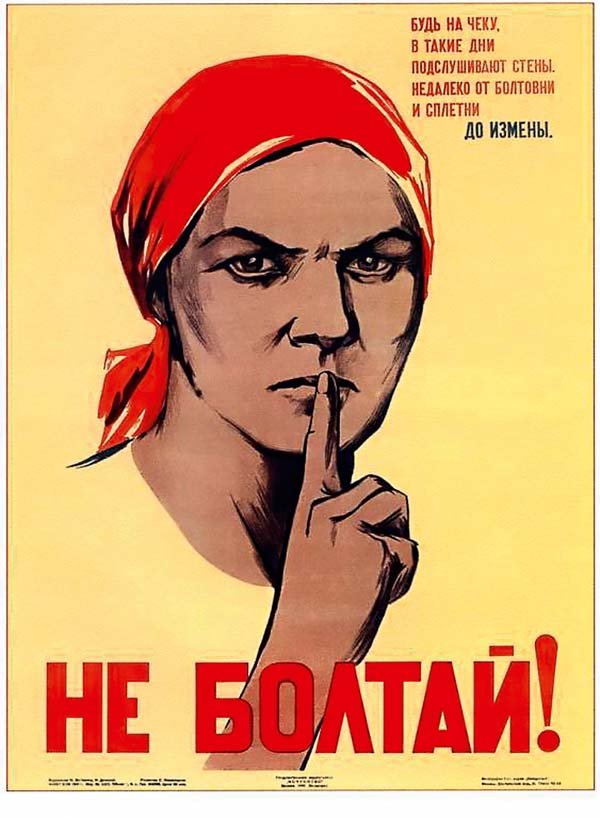

This Soviet-era poster says “Don’t gossip!.” Ukrainians still seem to be under the influence of this World War II propaganda. (Courtesy)

Some offices, however, go as far back in their communication model as asking journalists to mail their questions by post after sending a facsimile. No one seems to trust email either. I guess carrier pigeons will be next.

Explaining that journalists do not have to disclose their questions before the interview is like teaching calculus to a first-grader. PR agents and their bosses got spoiled by Ukrainian media that would reveal their agenda from the start.

Of course, Ukraine today is not the Ukraine of the Soviet Union, where suppression of free speech was ubiquitous. During World War II, posters with a lady pressing a finger against her lips as a sign to be quiet were adequate. Painter Nina Vatolina made the banner in 1941, when windows were being draped tight to prevent leaks. Vatolina’s neighbor posed for this work when her sons were already away at war.

A popular saying — that a talker is a godsend for the enemy – is sadly still kicking around. Interviewing people on the street today is hard. If they give you an honest comment, they usually don’t want to give you their name. And they don’t want their picture taken. Some of my colleagues noticed that it’s gotten worse since the change of president and government in February.

President Viktor Yanukovych’s administration claims there’s no censorship in Ukraine. Their officials, however, were recently exposed asking journalists not to release footage and photographs when Yanukovych was accidentally hit on the head by a memorial wreath.

I can’t remember former U.S. President George W. Bush banning video of a shoe thrown at him during a press conference. Nor can I recall French President Nicolas Sarkozy thwarting journalists’ shots of him standing on a small box while delivering speeches. Yes, Sarkozy is a short man, but not as petty and shortsighted as some Ukrainian autocrats.

I remember interviewing another big politician in Ukraine who mentioned Jesus Christ when asked who he would like to get on his team. It was a superb quote indicating the scope of the problems he is facing, and the divine powers it would take to meet the challenges. But he quickly disowned it, saying that some people may get offended by the reference to religion.

But he said it on record, during an official interview! By pulling the quote out, this politician confirmed a major pathology in the Ukrainian way of thinking: saying little about what really matters, thus stifling change and covering up problems.

Talking about the censored mentality, the popular Soviet movie from the 1980s, “The Envy of the Gods,” springs to mind.

In one of its episodes, an editor rushes from a fax machine to the studio, where anchors are already live on air. She passes them a news sheet, fresh from the Kremlin printers and ready for dissemination. When presenters read out the story, it becomes clear that it’s propaganda, not news.

Many Ukrainians are still afraid of communicating and making presentations. The problem is not 21st-century technology or Internet chat rooms quashing human interaction. The elderly and middle-aged say they fear government pressure and persecution. Youngsters, however, simply never learn how to articulate well. During recent BBC debates on education in Kyiv, many professors and employers complained that students are not taught how to communicate properly.

Hence, there’s little surprise we get monosyllabic press officers guarding their information instead of passing it on. To feel fully in control, they choose to interact by post.

Ironically, when I addressed the presidential press service with this problem, asking them to assist in getting information from one of the ministries, they said they had to go through the same procedure: fax the inquiries!

At the end of the day, the way we communicate with others often determines the quality of our lives – be it a chat with a waitress or a request for information from a civil servant. Writer Bernard Shaw one said that “the single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

In modern-day Ukraine, there are still plenty of these illusions, and still little communication.

Kyiv Post staff writer Yuliya Popova can be reached at [email protected]