BAKHCHISARAY, Crimea – After an evening prayer in the town of Bakhchisaray in southern Crimea, a handful of Crimean Tatars stand guard near the mosque where they pray to protect it and their people from a possible attack by pro-Russian militarized groups and ordinary criminals who they say increasingly roam the peninsula since the invasion of Russian troops in late February.

In recent days, unknown persons have been going around Crimean Tatar villages and marking their homes with white crosses, sowing panic among many women and outraging the men. The police here, who have been disoriented following the abrupt – and many claim illegal – change of power in Crimea last month, have neglected their duties.

This has left the Crimean Tatars themselves to move to ensure the safely of their homes and villages.

“Every evening men gather and patrol the streets to prevent provocations,” said Seitumer Seitumirov, 28, an economist by education.

In times of peace, Seitumirov runs an ethnic Crimean Tatar restaurant in Bakhchisaray, a popular tourist destination and one of the few places in Crimea that has preserved many elements of the rich Crimean Tatar culture, the most famous of which is the palace of Khan, or ruler, of the former kingdom of this ethnic group, which existed between the 15th and 18th centuries.

Seitimurov’s restaurant now closes at dusk to make sure that its workers get home safely.

Crimean Tatars are the largest ethnic community in Bakhchisaray, and make up about a third of its 26,500 population. In total, an estimated 300,000 Crimean Tatars live in Crimea, their native land.

Crimean Tatars were deported in 1944 at the behest of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and have spoken out against the Russian invasion in Crimea. Many of their communities have mobilized to protect their homes, but they don’t like to call them self-defense units, because the name is already used by the local Cossacks, ardent supporters of Russia who have been blocking Ukrainian military bases and terrorizing Ukrainian activists in Crimea.

“These Cossack groups have been formed of drunkards and unemployed and most of them came here from other regions and also from Russia,” said Said Seitumirov, a 26-year-old historian. He blames the Russian government for encouraging this group to disrupt order on the peninsula.

Just north of Bakhchisaray, in a suburb of Simferopol, some 50 Crimean Tatars warm up by a fire barrel. They are the guards of Mariyeno, a district where some 500 Crimean Tatar families live. They began patrolling their community on Feb. 27, the day Russian soldiers first stormed the peninsula.

Several more dozens of men are drinking tea inside the mosque while others nap, fully dressed, before their shift starts. There are several packages of food stacked nearby, prepared by Crimean Tatar women to be taken to the Ukrainian soldiers at Perevalnoye military base, which has been blocked by Russian troops.

They continue supporting Ukrainian soldiers and will boycott the March 16 referendum, despite rich offers from the new Crimean government. Sergei Aksynov, head of the Crimean government, said the Crimean Tatars would get to appoint a deputy prime minister and two ministers, and would receive $22 million in direct subsidies.

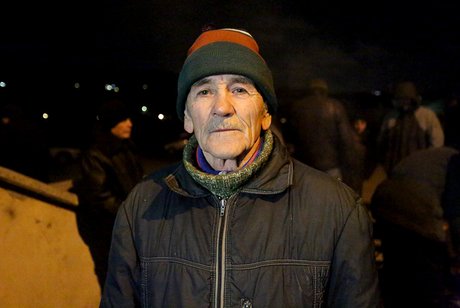

But Asana Ablayev, a 78-year-old Crimean Tatar man, says he has no trust in this offer because he remembers too well when, almost 70 years ago, men in military uniforms came into his family’s home and gave them 15 minutes to pack for resettlement to Central Asia or Siberia.

“We don’t believe in the Russian Federation, we are afraid they may deport us from our homeland again,” he said.

Despite the fact that both Ablayev’s father and elder brother served in the Soviet army, the family was still branded as the “enemies of the people” and was forced to leave their home. After spending 20 days in stuffy trains, Ablayev’s mother died of an illness.

He spent 10 years in an orphanage in Uzbekistan, during which he made two unsuccessful attempts to escape to Crimea. But it wasn’t until 1987 that he actually returned.

Ablayev thinks that his people are facing the biggest challenge since the time of deportation, and spends his nights on watch at the mosque.

“We, the old men, have to be ahead,” he said. “We don’t want our children to experience the same as we had.”

Fearing attacks, an estimated 150-200 Crimean Tatar families have already left the peninsula to resettle in western Ukraine. Their numbers are increasing, as the State Border Service reported on March 11 that in 24 hours prior some 265 people left the peninsula for mainland Ukraine, mostly Crimean Tatars.

Another potential destination for some of the fleeing Crimean Tatars is Turkey, where their diaspora counts a few million people. But most Crimean Tatars are determined to stay.

“Ukrainians have Ukraine, Russians have Russia, but Crimean Tatars have nothing except Crimea,” said Seitumer Seitumerov.

Head of the council of elders in Mariyeno, 65-year-old Iskander Suleimanov, says that it’s getting increasingly harder to pacify the younger Crimean Tatars, who are becoming outraged by the invasion of thousands of armed Russian troops and local militants who terrorize the peninsula.

He says although Crimean Tatar self-defense units have no weapons other than pitchforks, this can easily change.“We will of course find guns if we really need them,” Suleimanov said.

Young Said Seiturmerov agrees, but adds that turning into guerrilla warriors is not exactly what they want. “We are not afraid of war, but we don’t need it,” he said. “We realize that if it starts, it will last for very long.”

Kyiv Post staff writer Oksana Grytsenko can be reached at [email protected]. Kyiv Post photojournalist Anastasia Vlasova contributed to the story. She can be reached at [email protected].

Editor’s Note: This article has been produced with support from the project www.mymedia.org.ua, financially supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, and implemented by a joint venture between NIRAS and BBC Media Action.The content in this article may not necessarily reflect the views of the Danish government, NIRAS and BBC Action Media.