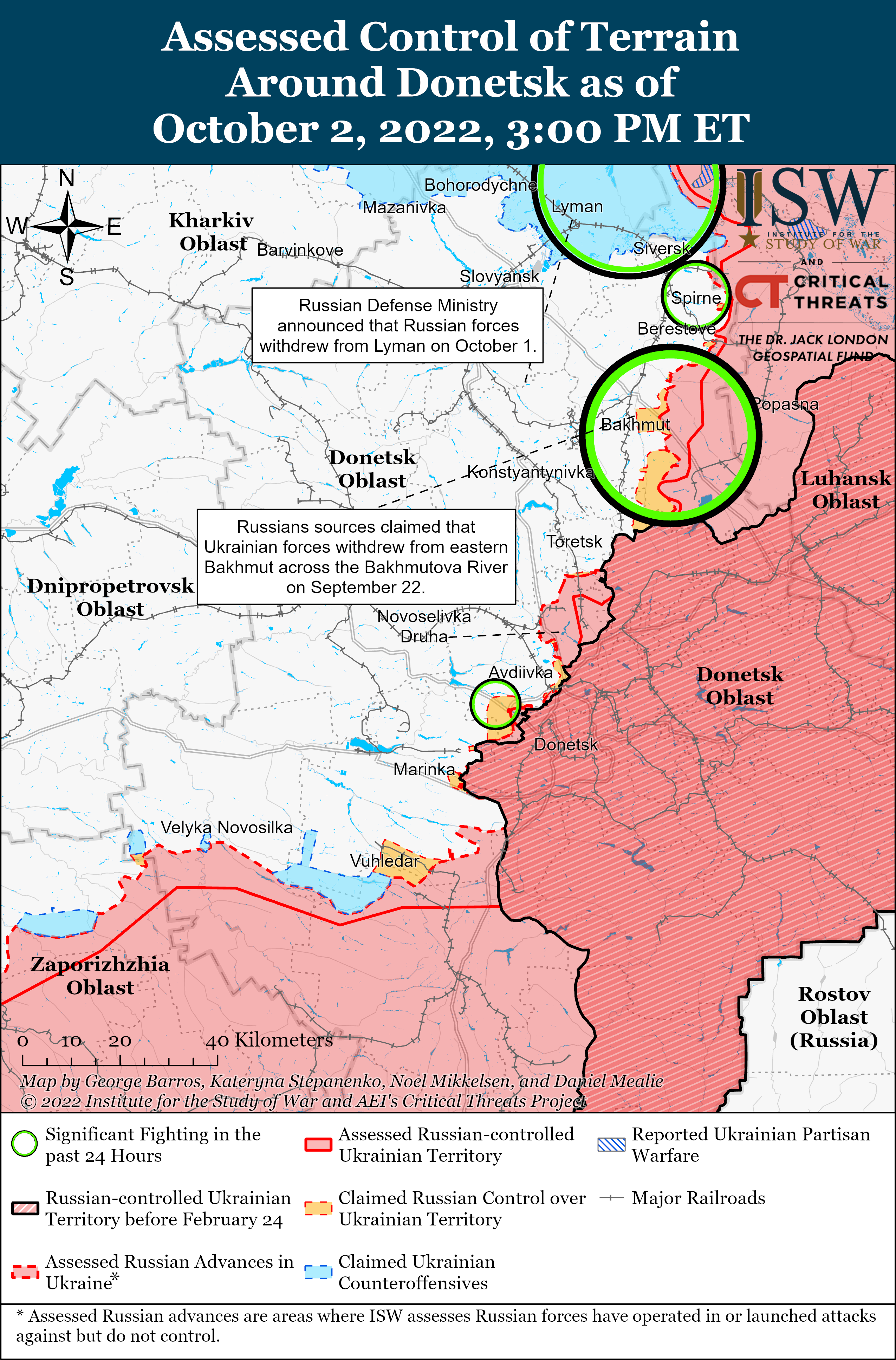

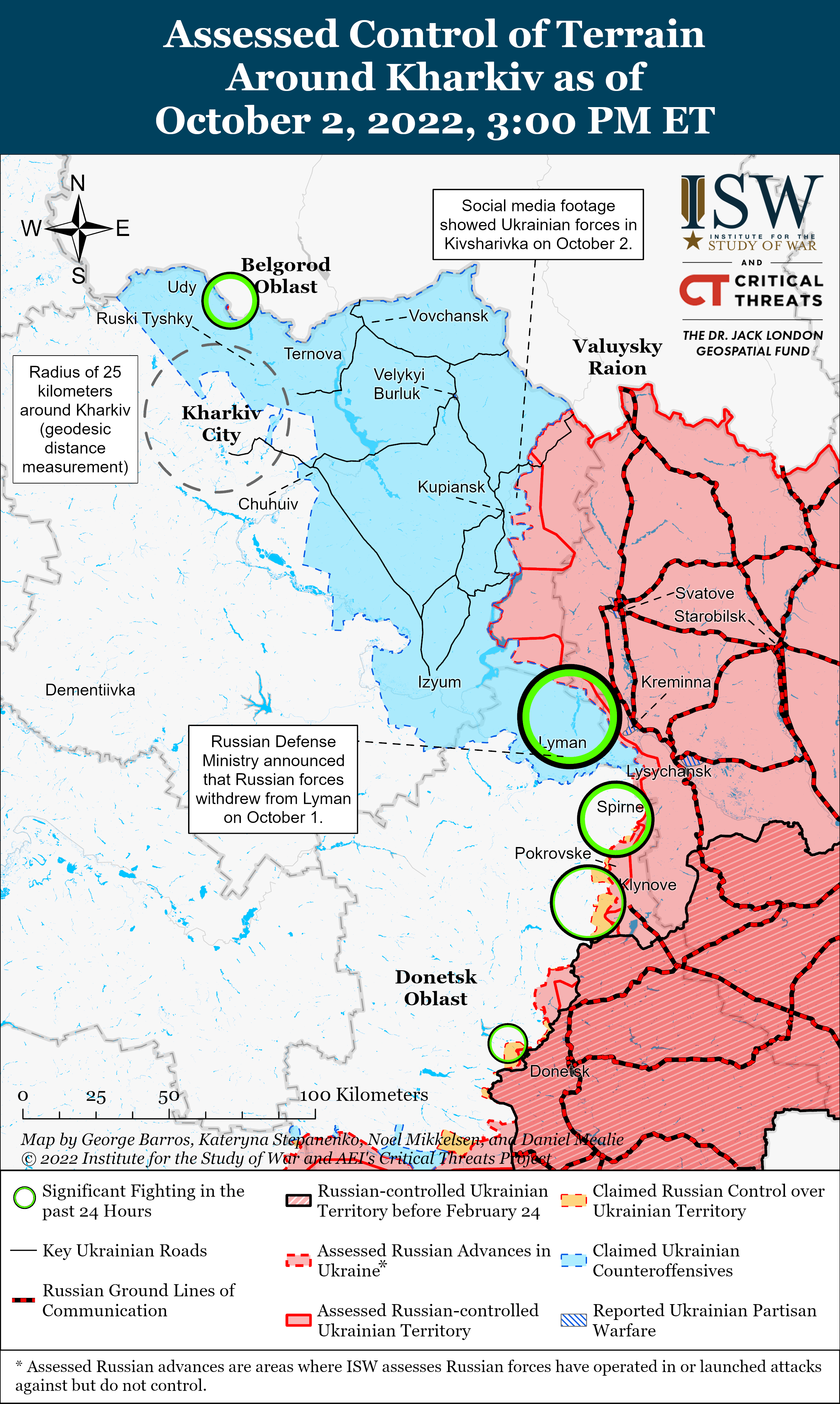

- Ukrainian forces continued to liberate settlements east and northeast of Lyman and have liberated Torske in Donetsk Oblast. Russian sources claimed that Russian forces withdrew from their positions northeast of Lyman, likely to positions around Kreminna and along the R66 Svatove-Kreminna highway.[24]

- Ukrainian forces continued to advance on settlements east of Kupyansk and liberated Kisharivka in Kharkiv Oblast.[25]

- Russian forces continued to launch unsuccessful assaults around Bakhmut, Vyimka, and Avdiivka.[26]

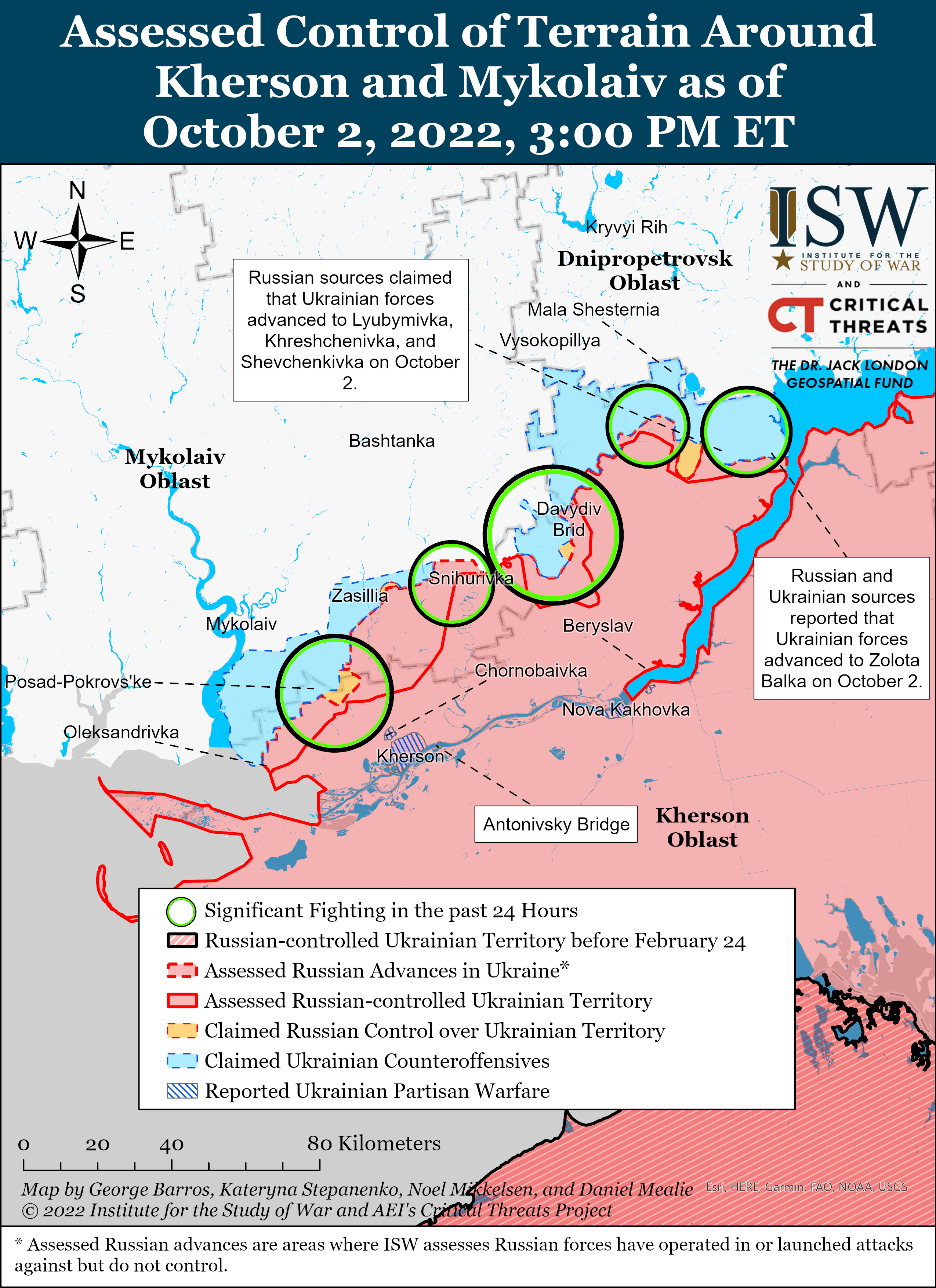

- Ukrainian forces resumed counteroffensives in northern Kherson Oblast and have secured positions in Zolota Balka and Khreshchenivka. Russian sources claimed that Ukrainian forces also liberated Shevchekivka and Lyubymivka, pushing Russian forces to new defensive positions around Mykailivka.[27]

- Russian forces continued to target Kryvyi Rih and Mykolaiv Oblast with Iranian-made Shahed-136 drones.[28]

- Russian State Duma MPs withdrew a law that would have given mobilized men a one-time payment of 300,000 rubles (about $4,980) and other benefits, without providing a reason for their decision.[29] Ukrainian military officials stated that Russian forces are forming a motorized rifle division with mobilized men from Crimea, Krasnodar Krai, and the Republic of Adygea.[30]

- Russian President Vladimir Putin submitted a draft law to the State Duma on admitting the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, and Zaporizhia and Kherson Oblasts, to the Russian Federation.[31]

This campaign assessment special edition focuses on dramatic changes in the Russian information space following the Russian defeat around Lyman and in Kharkiv Oblast and amid the failures of Russia’s partial mobilization. Ukrainian forces made continued gains around Lyman, Donetsk Oblast, and have broken through Russian defensive positions in northeastern Kherson Oblast. Those developments are summarized briefly and will be covered in more detail tomorrow when more confirmation is available.

The Russian defeat in Kharkiv Oblast and Lyman, combined with the Kremlin’s failure to conduct partial mobilization effectively and fairly are fundamentally changing the Russian information space. Kremlin-sponsored media and Russian milbloggers – a prominent Telegram community composed of Russian war correspondents, former proxy officials, and nationalists – are grieving the loss of Lyman while simultaneously criticizing the bureaucratic failures of the partial mobilization.[1] Kremlin sources and milbloggers are attributing the defeat around Lyman and Kharkiv Oblast to Russian military failures to properly supply and reinforce Russian forces in northern Donbas and complaining about the lack of transparency regarding the progress of the war.[2]

Some guests on heavily-edited Kremlin television programs that aired on October 1 even criticized Russian President Vladimir Putin’s decision to annex four Ukrainian oblasts before securing their administrative borders or even the frontline, expressing doubts about Russia’s ability ever to occupy the entirety of these territories.[3] Kremlin propagandists no longer conceal their disappointment in the conduct of the partial mobilization, frequently discussing the illegal mobilization of some men and noting issues such as alcoholism among newly mobilized forces.[4] Some speaking on live television have expressed the concern that mobilization will not generate the force necessary to regain the initiative on the battlefield, given the poor quality of Russian reserves.[5]

The Russian information space has significantly deviated from the narratives preferred by the Kremlin and the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) that things are generally under control. The current onslaught of criticism and reporting of operational military details by the Kremlin’s propagandists has come to resemble the milblogger discourse over this past week. The Kremlin narrative had focused on general statements of progress and avoided detailed discussions of current military operations. The Kremlin had never openly recognized a major failure in the war prior to its devastating loss in Kharkiv Oblast, which prompted the partial reserve mobilization.[6]

The Russian MoD has consistently focused on exaggerating Russian success in Ukraine with vague optimistic statements while omitting presentations of specific details of the military campaign. The daily Russian MoD briefing has claimed to capture the same villages more than once as ISW and independent investigators have observed, and the Russian MoD rarely releases photographic evidence confirming claims of Russian advances. [7]

The Russian MoD has sought to impose this kind of narrative on the milbloggers as well. Advisor to the Russian Defense Minister Andrey Ilnitsky called on Russian journalists and milbloggers on May 26 to refrain from presenting detailed coverage of the war and to avoid publishing negative information that could help the West infiltrate the Russian information space and win the “hybrid war.”[8]

The milbloggers largely disregarded the MoD’s directives, and Putin seemed to support them in this disobedience, rewarding them with a lengthy personal meeting on June 17.[9] Most milbloggers have continued to report Russian battlefield setbacks and to criticize failures in the partial mobilization, often in strident tones. Putin has not apparently punished any major milbloggers for their outspokenness or allowed others to punish them. He has, however, kept their critiques off of the mainstream Russian airwaves. Kremlin mouthpieces on federally-owned TV channels had continued to puppet the MoD and Kremlin lines for the most part—until the partial mobilization.

The Kremlin’s declaration of partial mobilization exposed the general Russian public to the consequences of the defeat around Kharkiv and then at Lyman, shattering the Kremlin’s efforts to portray the war as limited and generally successful. The Russian defeat around Lyman has generated even more confusion and negative reporting in the mainstream Russian information space than had the Russian withdrawals from Kyiv, Snake Island, or even Kharkiv. The impact of Lyman is likely greater because Russians now fear being mobilized to fix problems on the battlefield. An independent Russian polling organization, the Levada Center, found that more than half of respondents said that they were afraid that the war in Ukraine could lead to general mobilization, whereas the majority of respondents had not voiced such concerns in February 2022.[10] Russians also likely see that the Kremlin is executing the current partial mobilization – which was supposed to be a limited call-up of qualified reservists – in an illegal and deceptive manner, which places more men at the risk of being mobilized to reinforce collapsing frontlines.

Putin relies on controlling the information space in Russia to safeguard his regime much more than on the kind of massive oppression apparatus the Soviet Union used, making disorder in the information space potentially even more dangerous to Putin than it was to the Soviets. Putin has never rebuilt the internal repression apparatus the Soviets had in the KGB, Interior Ministry forces, and Red Army to the scale required to crush domestic opposition by force. Putin has not until recently even imposed the kinds of extreme censorship that characterized the Soviet state. Russians have long had nearly free access to the internet, social media, and virtual private networks (VPNs), and Putin has notably refrained from blocking Telegram even though the platform refused his demands to censor its content and even as he has disrupted his people’s access to other platforms. The Russian information space has instead relied on journalists and TV talk-show guests to enforce coerced self-censorship, especially after the Kremlin adopted a law that threatens Russians with up to 15 years in jail for “discrediting the army.”[11] The criticism on Russian federal TV channels of military failings and failings of the partial mobilization effort, especially following the defeat at Lyman, is thus daring and highly unusual for the Kremlin’s propaganda shows. It has brought the tone and tenor of some of the milblogger critiques of Russia’s performance in the war into the homes of average Russians through official Kremlin channels for the first time.

Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov and Wagner Private Military Company financier Evgeniy Prigozhin have further damaged the Kremlin’s vulnerable narratives during and after the fall of Lyman. Kadyrov published a hyperbolic rant on October 1 in which he accused the Russian military command of failing to promptly respond to the deteriorating situation around Lyman and stated that Russia needs to liberate the annexed four oblasts with all available means including low-yield nuclear weapons.[12] Prigozhin reiterated Kadyrov’s critiques of the Russian military leadership. The West‘s focus on Kadyrov’s nuclear threat obscured the true importance of these statements.

Kadyrov and Prigozhin are bona fide members of the small group of leaders Russians call siloviki—people with meaningful power bases and either membership in or direct access to Putin’s inner circle. Kadyrov has a history of irresponsible statements and boasts that do not always grab headlines or shape narratives in Russia. Prigozhin is not a normally dominant voice either, although his prominence has grown in recent weeks.[13] But their statements on October 1 have had a profound effect on the Russian information space. Together they broke the Kremlin’s narrative that attempted to soften the blow of the defeat around Lyman. Federal outlets had largely expressed hopeful attitudes that newly mobilized men and deployed reinforcements could either hold the line or conduct counter-attacks in the near future, prior to Kadyrov’s statement.[14] But talk shows on federally-controlled channels picked up immediately on the Kadyrov-Prigozhin statements, prompting commentators on live television to add to the criticism of the higher military command.[15] The Kremlin’s propagandists even had to disrupt the presentation of the former Russian Southern Military District (SMD) Deputy Commander Andrey Gurulyov when he started to blame the higher military command for the defeat in Lyman during a live broadcast.[16]

Kadyrov and Prigozhin’s statement likely publicly undermined Putin’s leadership, possibly inadvertently. Kadyrov specifically targeted the commander of the Central Military District (CMD), Colonel General Alexander Lapin, and accused Chief of the General Staff Army General Valery Gerasimov of covering up Lapin’s failures in Lyman. Putin had publicly expressed his trust in Lapin when the Russian MoD announced Lapin’s victory around Lysychansk on June 24.[17] Western military officials have also reported that Putin has been making operational military decisions in Ukraine and micromanaging his military command.[18] Putin is thus likely responsible for the decisions not only not to reinforce Lyman but also to attempt to hold it–facts that are probably known to a number of people in his inner circle at least.[19] Kadyrov’s direct attack on Lapin is thus an indirect attack on Putin, whether Kadyrov realizes it or not. Putin and his mouthpieces have been extremely tight-lipped about the performance of the military commanders or their replacements, which makes Kadyrov’s statement and Prigozhin’s echo of it especially noteworthy.

Putin likely recognizes the dangerous path Kadyrov and Prigozhin had begun to walk, prompting push-back by Kremlin-controlled voices and milbloggers against the direct critiques of military commanders. Federal television channels characterized Kadyrov’s statements against Lapin as rather “harsh,” while milbloggers argued that the Russian MoD is more responsible for the defeat claiming that Lapin was not in command of the Lyman garrison.[20]

Putin has not previously censored nationalist milblogger figures, Kadyrov, war correspondents, and former proxy officials, likely because he has seen them as voices pushing for his preferred policies that Russians willing to support him are more likely to trust. ISW has previously assessed that Putin is likely attempting to keep the milbloggers on his side and to use them to establish new scapegoats for his failures in Ukraine.[21] Putin may also have obtained a more unvarnished view of what is occurring on the frontlines than he was getting from the chain of command, which may be one of the reasons he met with the milbloggers in mid-June. Milbloggers likely have a reputation with their audiences of being more accurate sources than the Russian MoD because they report setbacks and mistakes while advancing pro-war and patriotic views. Putin likely seeks to retain the favor of the audience these nationalist figures reach as they promote his grandiose vision for the war.

The milblogger community may begin to undermine Putin’s narratives to his core audience amidst the defeats and failures of the Russian war in Ukraine, however, especially as their narratives spread to mainstream Kremlin-controlled outlets. Milbloggers are increasingly appearing on Russian state television and in Kremlin-affiliated outlets following the collapse of the Kharkiv frontline and are boldly pointing out failures in the Russian military campaign while exaggerating the need for Russia to win the war and the price Russians should be prepared to pay.[22] Putin likely attempted to win back some of the milbloggers by inviting them to his annexation speech in Moscow and by integrating them into the mainstream media.[23] But mibloggers are fueling impossible expectations and making demands that Putin and the Russian government cannot possibly meet. They insist that Putin seize all of Ukraine when Russian forces are only capable of making incremental territorial gains around Bakhmut and Avdiivka. They are calling on Russian military recruitment centers and the Russian MoD to fix the generational bureaucratic issues plaguing partial mobilization. They are likely adding to the domestic problems Putin will face in the coming months, however much it may seem to Putin that they are helping him through a hard time.

Putin may be experiencing an odd variant of the problems Mikhail Gorbachev encountered resulting from his glasnost’ (openness) policy. Gorbachev partially opened the Soviet information space in the mid-1980s in the hopes that Soviet citizens would give him insight into the causes of bureaucratic dysfunction within the Soviet state that he could not identify from above. But Soviet citizens did not stop where Gorbachev wanted or expected them to and instead began attacking the entire Soviet system. The reforms (perestroika) he initiated after a period of glasnost’ ended up destroying the Soviet Union rather than strengthening it.

Putin is no doubt fully aware of this pattern and surely has no intention of repeating it. He has never established Soviet-level degrees of control over the Russian information space even as he has steadily narrowed it to only platforms he tolerates. He has absolved the milbloggers of having to adhere to Kremlin-approved narratives while keeping open the platform on which they present to a core constituency on which he relies, and he is now mainstreaming them further. It remains to be seen how much Putin will tolerate and what will happen if and when he attempts to shut down the milbloggers and their critiques, increasingly of his own decisions, that he has allowed for the moment to circulate in Russia.

Authors: Kateryna Stepanenko and Frederick W. Kagan

See the full report here.