Competitive video gaming, or esports, is now an official sport in Ukraine. And just like in football or tennis, local esports athletes need a place to train and play.

They used to do it in the comfort of their homes or in local internet cafes where tech-savvies competed in video games like Dota 2 or Counter-Strike.

But as esports turned from a solitary hobby into a multimillion-dollar industry, professional gamers started to look for bigger venues to play. Today they open modern esports clubs and build arenas to hold competitions and stream them online.

Places like that have started to pop up across Ukraine too. Real-life arenas attract sponsors, a crucial revenue stream for esports. They also make people realize that esports is not just about video games played by geeks — it is a real sport.

Such arenas, however numerous in Ukraine, aren’t very profitable yet. But that could change soon.

Untamed market

Ukraine has esports arenas of all types. Some of them look like bars with hookahs, bean bags and high-end computers dotted around the place. Others are equipped with massive screens and cameras to stage live esports events.

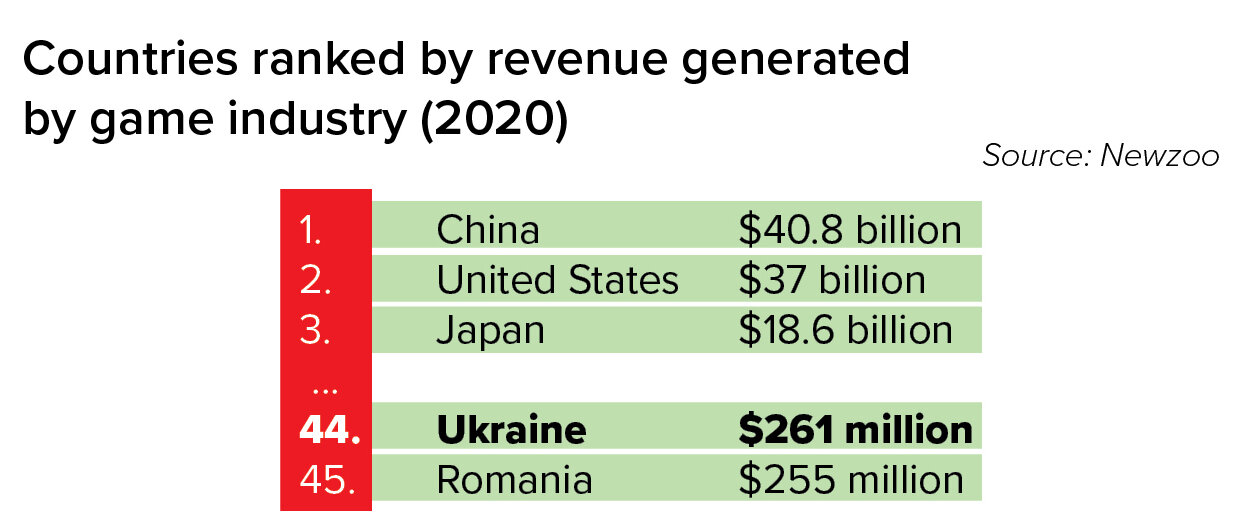

Esports athletes from China, Brazil, the U.S. and Western Europe visit Ukraine often. For foreign players, Ukraine is a convenient location with high-speed internet and cheap accommodation.

Local esports enthusiasts open arenas mostly in big cities like Kyiv, Kharkiv and Dnipro, but smaller towns have esports venues too, albeit more modest.

For many Ukrainians these are the only places where they can meet like-minded people and play video games on modern computers, said Genadiy Veselkov, cofounder of Kyiv’s esports arena ASUS CyberZone and local esports bar NaVi bar.

But it’s still niche. The country doesn’t need more esports arenas at the moment, according to Ivan Danishevsky, president of Ukraine’s Esports Federation. “Now it is more important to fill arenas with people rather than cities with arenas,” Danishevsky told the Kyiv Post.

New opportunities

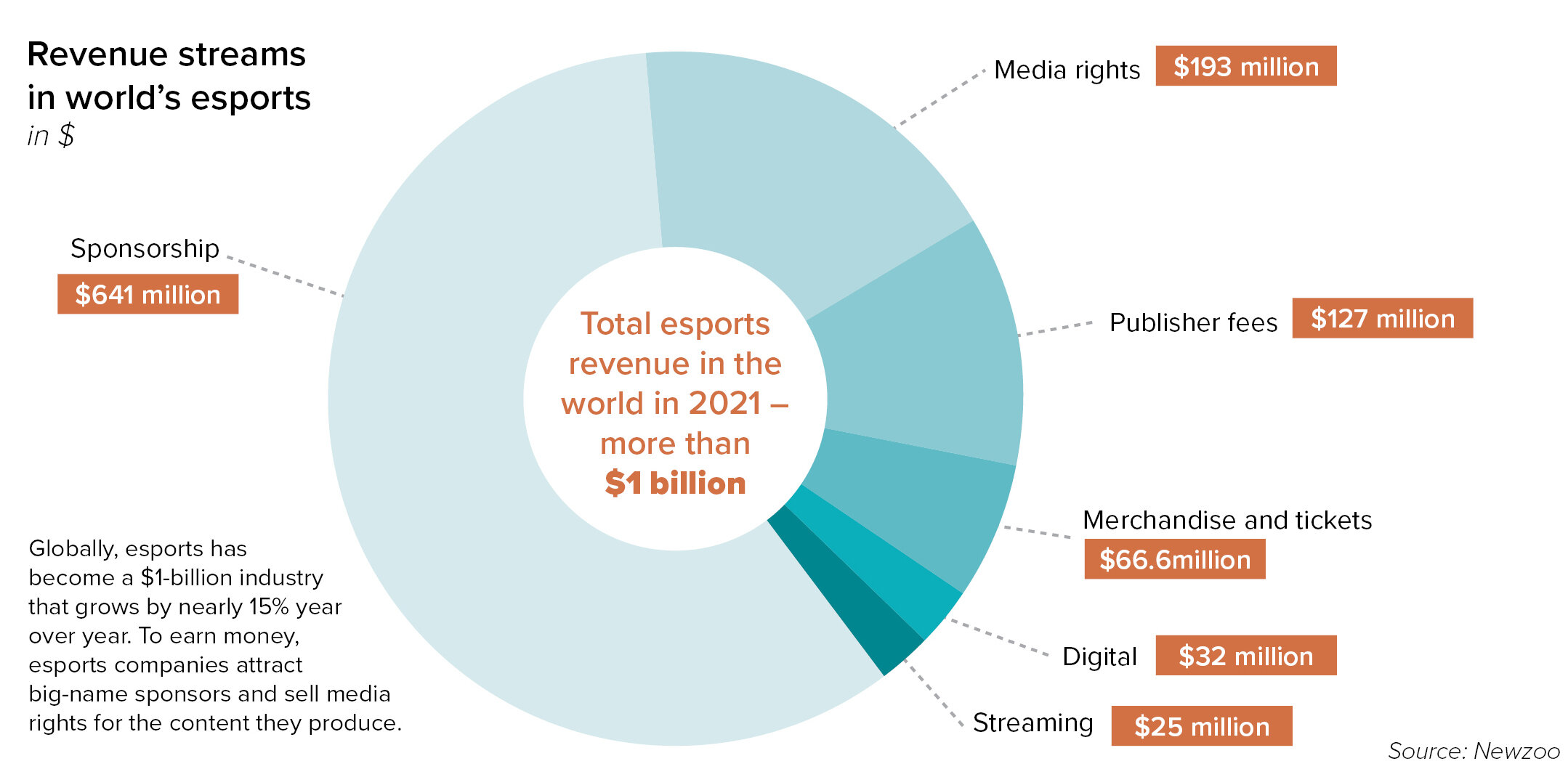

Globally, esports is a $1 billion industry with 500 million followers. Nearly $600 million of its revenue in 2020 came from sponsorships and only $50 million from selling merchandise and tickets to esports events.

However, businesses around the world continue to construct facilities for esports and try to make them financially sustainable.

For example, the $50 million Fusion Arena in the U.S. can host up to 3,500 esports fans, while the world’s first esport stadium built from the ground up in China can seat over 7,000 viewers.

Ukrainian experts said that esports need arenas to thrive. Arenas allow players to compete in equal conditions — with the same internet connection and equipment, according to Maksym Bednarsky, the founder of Esports Club Kyiv, an esports team that competes in Counter-Strike tournaments.

Besides, real-life tournaments bolster competition and challenge esports athletes, Bednarsky said.

“You can play online endlessly but both viewers and esports athletes love to perform in big stadiums, go to the stage, feel support from the audience,” said Stepan Shulga, head of esports at Parimatch Tech, a software developer belonging to betting firm Parimatch.

Esports businesses benefit from such tournaments too: When the tournaments are held offline, it is easier to attract sponsors and advertisers, said Maksym Bilogonov, general producer and chief visionary officer at Ukrainian esports media holding company WePlay Esports.

Lucrative business

The explosive growth of esports in Ukraine has caught the eye of companies like Pepsi, McDonald’s and Parimatch. Popular esports sponsors also include electronics manufacturers and retailers like Citrus, GT Race and Hator. They give professional gamers computers, keyboards, headsets and monitors, according to Denis Zhurid, an esports commentator.

Tech companies are interested in esports because it helps them to reach the audience that brings profit, said Artur Yermolayev, founder of Windigo Arena in Dnipro, the city of almost 1 million people located 480 kilometers southeast of Kyiv. According to esports analytics firm Newzoo, the majority of esports enthusiasts in Europe are age 25, so they are more likely to buy expensive esports devices.

Sponsors are also willing to support star esports players. Athletes can make millions of dollars by winning prize money and starring in ads.

For example, Ukraine’s accomplished esports team NaVi has earned nearly $11 million in prize money in the past 10 years. It has many sponsors, including Newzoo, U.S. tech company Nvidia, Chinese streaming service Huya and Swedish electronics manufacturer Logitech.

Esports athletes play video games during a Mortal Kombat 11 tournament WePlay Dragon Temple at the WePlay Esports Arena Kyiv on Dec. 10, 2020. Like other athletes, esports players need equipped venues to train and play. (Courtesy of WePlay Esports)

Ukrainian arenas

Big esports tournament is a show accompanied by music and special effects. To arrange it, arenas need to have a stage, massive screens and a lot of seats.

An arena like that cost Ukrainian WePlay Esports $5 million.

To build a 1,000 square-meters esports stadium tucked inside a historic building at Kyiv’s VDNG exhibition center was a challenge for WePlay Esports. VDNG is considered Ukraine’s cultural heritage, so the company couldn’t redesign the old building or change its exterior. Bilogonov said that the company needs “dozens of permits” even to repair the roof that leaks.

Despite the Soviet-like style of the building, the arena inside it looks futuristic. It has a 60-square-meter stage surrounded by huge screens and bleachers for nearly 200 visitors. It also has rooms for the production and media teams and areas for hosts and commentators.

Before WePlay Esports opened its own arena in Kyiv, it organized tournaments in places temporarily redesigned for esports tournaments.

One of them, the international Dota 2 competition WePlay! Bukovel Minor with a prize pool of $300,000, took place in January 2020 in Bukovel, Ukraine’s biggest ski resort. Nearly 160 people visited it for free, while over 93,500 viewers watched the games online.

But temporary venues aren’t flexible and it takes time to reach agreements with their owners. Having its own place, the company can host esports competitions at any time and adjust the stage to different games, Bilogonov told the Kyiv Post.

For example, during the Mortal Kombat 11 competition in December 2020, the stage was decorated with Chinese pagodas and fake sakura trees to fully immerse viewers into the fighting game.

“This arena meets all our creative desires,” Bilogonov said. “We can do whatever we want there.”

WePlay Esports streams games for thousands of viewers on YouTube or Twitch, the Amazon-owned streaming platform. The company can also sell media rights for this content to other esports platforms.

Other Ukrainian arenas have a different business model. They look more like gyms where esports athletes train and play.

Yermolayev’s 1,100-square-meter Windigo Arena in the center of Dnipro has 154 powerful computers and a massive screen to broadcast games. Visitors pay $1.2 per hour to play there.

Zeus Arena in Kharkiv, the city of 1.4 million people located 480 kilometers east of Kyiv, has a bar, a restaurant and many playing areas for gamers. The arena also hosts tournaments and streams the games on Twitch.

Ukraine recognized professional video gamers as athletes in September 2020, making esports an official sport in the country. Esports is now considered a non-Olympic sport.

Esports entrepreneur Alexander Kokhanovskyy also bought Kyiv’s central Dnipro Hotel for $41 million earlier in July to turn it into the first hotel in Europe dedicated to esports. Hotel rooms in Dnipro will be equipped with huge screens and computers, Kokhanovskyy said in an interview with the Kyiv Post earlier in September.

According to him, esports could bring thousands of jobs and millions of dollars to the country through gaming tournaments, given Ukraine has good infrastructure to host such events.

“We want to make Kyiv a European mecca for esports,” Kokhanovskyy said.