You may ask me why I gave such an odd title to this particular piece. The answer is very simple: the protagonist of my story, a cultured, well-to-do and very pragmatic man, once expressed himself quite aphoristically: It is easy to love Ukraine to the bottom of your heart. Try loving it to the bottom of your pocket.” And it was no lip service – he lived as he preached.

It is not the first time his name resurfaces in the public discourse in contemporary Ukraine. However, the recent electronic vote in Kyiv turned him – in a way – into an antagonist of Alexander Pushkin: Kyiv voters suggested renaming Pushkin Street after Yevhen Chykalenko. What the Ukrainian writer and politician Volodymyr Vynnychenko wrote in a letter to Chykalenko back in 1908 may now come true: “I believe we will have to choose a street or square to put up a monument to you.”

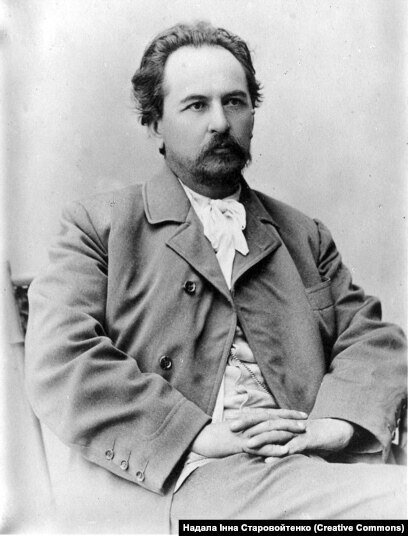

Yevhen Chykalenko

A public figure, publisher, political writer, landowner, agronomist and philanthropist, Yevhen Chykalenko lived to see his 67th birthday. He was born in December 1861 in the small village of Pereshory, now the Odesa region, and died in June 1929 in Prague. His emigration was quite expected since he advocated for convening the Tsentralna Rada (Central Council, the first government of the Ukrainian People’s Republic) in the pivotal year of 1917, and for electing Mykhailo Hrushevsky to chair it. The Russian Wikipedia defines Chykalenko as a “nationalist.” In fact, he was not a nationalist as such. It is true that he sponsored Ukrainian projects, but where did the money come from?

Yevhen Chykalenko was a very skilled businessman. It all started in 1883, when Chykalenko, a free student at the Natural Sciences dept. of Kharkiv University, was arrested because of his connections with local volunteers. After the books on him were closed, he was sent to Pereshory to stay under police supervision. His father died and he had to take over the responsibility for his family’s well-being. He plunged into agricultural studies, experimenting in the fields around Pereshory. And his hard work paid off: thanks to the use of black steam, his fields yielded rich harvests even in dry and locust years. Authoritative scientists came to the village to see to their surprise that while the neighboring farms were suffering from the drought, Chykalenko’s black soil yielded a rich harvest.

Later, Chykalenko’s daughter Anna would write that her father had a great power of perseverance: adverse circumstances only increased his tenacity. “For seven years, we all have been living under the sign of black steam,” she recalled. “It was his idea that he lived and inspired others with.” It should be mentioned that Chykalenko did not hide the secrets of his success. He published small books where he wrote about black steam, horticulture, viticulture, and animal husbandry. In addition, he was engaged in breeding valuable breeds of steppe horses and sheep.

To put it all together, he was a successful entrepreneur. He could have saved money and led a wealthy life, but he did not. In 1894, the Chykalenko family settled down in Odesa (but every year, from early spring to late fall, he lived in Pereshory where his wife and children joined him for the summer). Years later, he wrote: “Spending a grand part of my year in Odesa, surrounded exclusively by likeminded members of the community who were guided by nationalist ideology, and often visiting Kyiv to deal with civic affairs, I became more and more involved in the Ukrainian liberation movement and finally came to admire it with all my heart. I lost interest in my farm and paid less and less time and attention to it. After a while, I began to view it as a mere source of means for my livelihood and public needs.”

Now he was putting not only his financial but also intellectual resources and managerial skills into the Ukrainian cause. In 1899, he bought an estate in the village of Kononivka, then Poltava province, and moved to Kyiv. He kept in touch with Volodymyr Antonovych, Serhiy Yefremov, Mykhailo Kotsyubynsky, Panas Saksagansky (Tobilevych), Mykola Lysenko, Dmytro Doroshenko, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, and many other prominent people. Among Ukrainian projects supported by Chykalenko was an award “For the best-written single-volume book on Ukrainian history for readers at the public teacher’s educational level”; Rada, the first pre-WW II Ukrainian language daily newspaper in Dnieper Ukraine; Borys Hrinchenko’s Ukrainian Language Dictionary“(1907-1909); and publications of works by Ivan Franko, Mykhailo Kotsyubynsky and Volodymyr Vynnychenko. Chykalenko sponsored the opening of book collections, the Shevchenko Scientific Society, and the construction of the Academic House for Ukrainian students from the Dnieper region in Lviv in 1905 (to which he donated 25,000 rubles) …

Unlike some present-day Ukrainian oligarchs, Yevhen Chykalenko never entered the world of politics. In March-October 1917, Chykalenko, as usual, was farming in Pereshory. During the time of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky, he was invited to head the central government or the ministry of agriculture, but he refused.

In 1919, after the Bolsheviks again occupied Kyiv, Yevhen Chykalenko emigrated. Through Poland and Austria, he reached the lands of former Czechoslovakia. Now he channeled all his efforts into helping the large local Ukrainian community, especially the young people. Chykalenko taught at the Ukrainian Academy of Economics in Poděbrady and headed the terminology commission. The commission was studying Ukrainian terminology in mathematics, natural sciences and engineering, and was also working on The German-Ukrainian Forestry Dictionary and The Russian-Ukrainian Agricultural Dictionary. However, nostalgia and illness did eventually take their toll. Poděbrady became the last earthly address of this extraordinary man.

Yevhen Chykalenko was not only a philanthropist, but also, in a way, a chronicler of his times. He kept a diary and left behind interesting memoirs covering the period between 1861 and 1907. They are a valuable source for researchers of that epoch.

Let me conclude with Chykalenko’s words: “I bless my fate for letting me live to see the fight of Ukrainian intellectuals and common people for their state. This struggle, this blood will not be lost in vain… Sooner or later, there will be Ukraine!”

Yuriy Shapoval,

Professor, PhD History