ODESA, Ukraine — To the sounds of children’s laughter, the meowing of kittens and distant tunes of jazz, the angry activists rallied on May 12 in the City Garden in Odesa’s historic center. They were demanding that police stop illegal construction at the site of the abandoned Summer Theater.

Surrounded by lush trees, this historic site has become the epicenter of the fights between the local environmentalists and thugs hurling feces as a weapon.

In Odesa, the Black Sea port city of 1 million residents located 475 kilometers south of Kyiv, beauty often coexists with ugliness.

On May 7, at this construction site, a man poured a bucket of feces on environmental activist Svitlana Pidpala. On April 19, the same happened to lawmaker Mustafa Nayyem. Both had criticized plans to build an eight-story trade center at this historic site by company SP Soling, which activists link to Vladimir Galanternik, an influential yet secretive businessman, a crony of Aleksander Angert, a local businessman with a criminal past, and Odesa Mayor Hennady Trukhanov.

Activists say this group owns a number of ill-gotten development projects in Odesa registered to foreign offshore entities. A 1998 Italian police dossier published by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project in 2016 identified Trukhanov and Angert as members of a mafia gang.

SP Soling and publicly shy Galanternik weren’t available for comment. Trukhanov’s press service didn’t respond to a request for comment.

So far, the police have failed to find the “feces” attackers in Odesa. On May 4, Trukhanov called the environmentalists who criticize him “morons and idiots.”

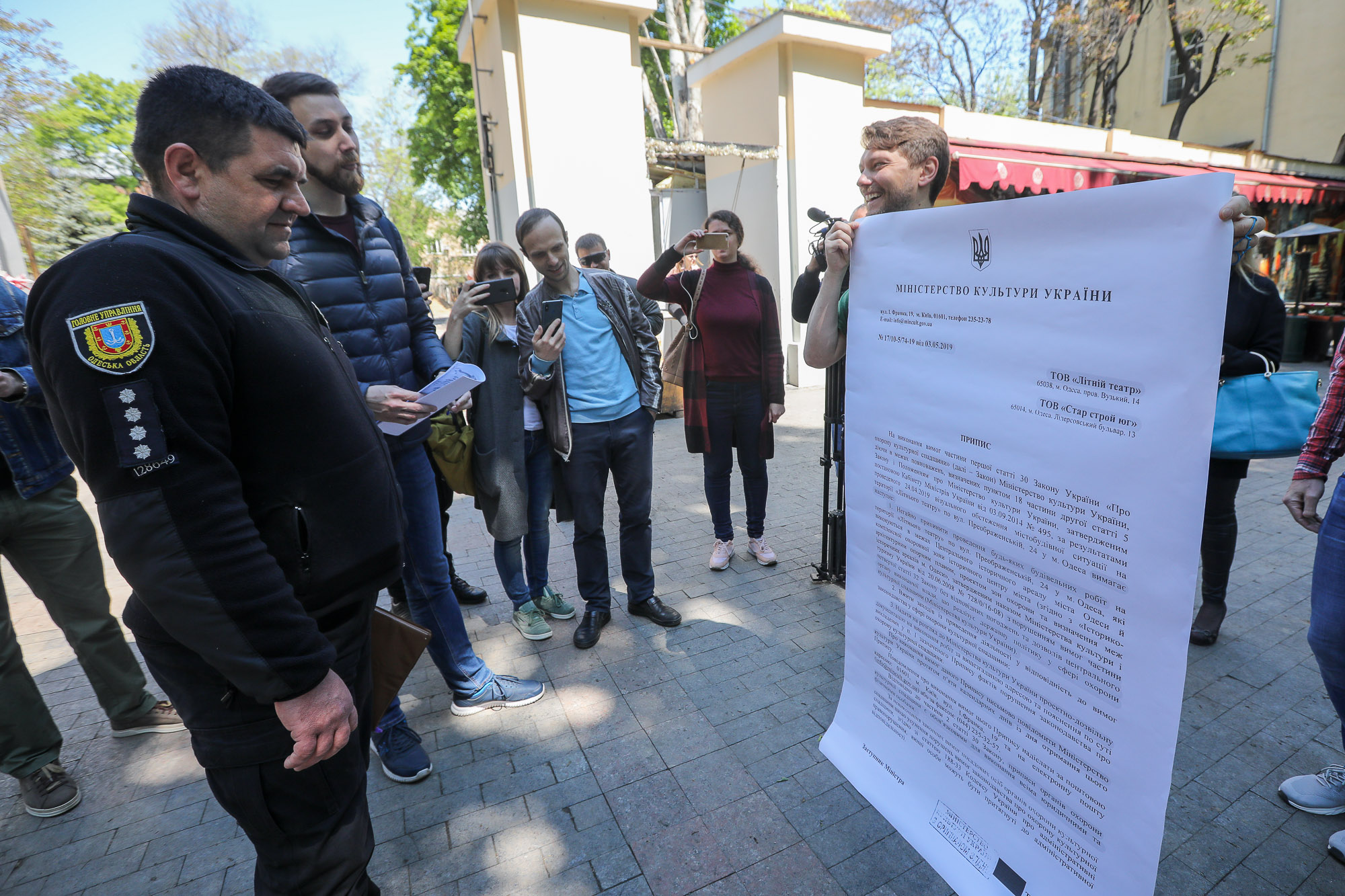

The police officers showed little enthusiasm on May 12, when the activists showed them a printed copy of an instruction from the Ministry of Culture, which urges a stop to any construction work at the Summer Theater until the ministry sees the plans and approves them. The police officers just checked the papers of the builders and swiftly left.

In the evening of the same day, a poster featuring the ministry’s instruction was torn down from the theater’s wall. Construction work resumed in the morning. But the fight is not over.

Unlike most other Ukrainian cities, Odesa is known for its strong city activism and the high risks activists face for it. At least 14 local activists were attacked in the city last year. Most of them blamed Trukhanov and his cronies for ordering or sanctioning the attacks. One of them, Oleg Mykhailyk, nearly died after being shot in his chest on a city street in late September.

But with the election of a new president, power in Odesa is being shaken up.

The local governor was dismissed and the oblast police chief resigned. The methods used against activists have changed as well. Shootings and beatings were replaced with feces, court hearings, and smear campaigns.

“Now the authorities, including Mayor Trukhanov, are hurrying up to snatch all they can,” Mykhailyk told the Kyiv Post. “They keep exploiting lawlessness, but they are afraid to act as radically as they (previously) did.”

Anti-corruption activist Oleg Mykhailyk poses for a photo on May 11, 2019, on a street where he lives in Odesa downtown. Mykhailyk was shot on the same street in September for his civic activity as he believes. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

‘Toilet scheme’

People in Odesa like to recall the story that the territory of the City Garden was granted to Odesa residents “in perpetual use” by Felix de Ribas, brother of the city’s first mayor, Jose de Ribas, in the early 19th century.

When the City Garden underwent major reconstruction in 2007, the Summer Theater, which is a part of it, remained abandoned and closed. Then, in 2017, residents discovered that the city authorities had allowed the trees on its territory to be chopped down, which indicated the beginning of construction work.

In November 2017, hundreds of activists stormed the gates of the construction site, which led to scuffles with the police. Then local residents started regularly cleaning the territory of the Summer Theater and planting trees there to preserve this site for the city.

A local deputy, Liliya Leonidova, published papers from the City Council’s urban planning department showing that, in 2016, the authorities leased the territory of the Summer Theater — up to 0.7 hectares — to the SP Soling firm for 49 years for the construction of an eight-story trade and entertainment center. The stage, the cash-office, a fence and a toilet at the abandoned theater were sold to the same firm back in 2003, according to the same documents published by Leonidova on Facebook.

Mykhailyk calls this a “toilet scheme,” in which some minor object is bought by a company in order to later grab a lucrative piece of land around it and then build something there. He said it has been commonly used in Odesa in recent years.

Vitaliy Ustymenko, head of the Odesa branch of the AutoMaidan civic movement, said that Galanternik “simply purchased SP Soling with all its small houses and huts and received the land in lease from the City Council.”

In 2017, SP Soling, which was registered back in 1997, indeed changed its owner to Cyprus-registered firm Maresenia Investment Limited, according to the YouControl open data registry.

Ustymenko said that the mass public protests in 2017 made the developers and authorities change their strategy. Now the company claims they plan just to reconstruct the old Summer Theater, whose pictures they even placed on the wall of the construction site. But Ustymenko believes a theater could be constructed only temporarily in order tto later build a huge building at that site as indicated in the construction plans.

“They will drive the activists from this process and then they will build whatever they want,” he said.

New methods

While a dozen activists argued with police officers and construction workers on May 12, a group of athletic young men observed this scene from a distance, grinning and joking about the recent “feces attacks.”

Ustymenko said that they were paid thugs hired by SP Soling to oppose activists. Apart from the thugs, there are activists of Automaidan Odesa, a group that broke off the Automaidan movement and often participates in public rallies on the side of Trukhanov.

There are other ways to fight activists.

In March, SP Soling filed lawsuits against 13 activists, including Ustymenko and Pidpala, demanding Hr 1 million ($38,000) from each of them. The firm accuses them of “damaging property” of the company at the construction site.

The company also lured a respected local showman, Dmytro Shpinariov, and made his firm a subcontractor in the urban design of the Summer Theater, trying to attract more supporters to the project this way. On April 13, at a meeting with activists, Shpinariov assured them that there will be no trade center constructed at this site. “I don’t know if he (Shpinariov) understands that he’s being used,” Ustymenko said.

Shpinariov told the Kyiv Post he doesn’t know who is attacking the activists at the Summer Theater, since its territory is now open and “anybody can come there.” He claimed the builders don’t violate the ministry’s instruction because there’s “not construction, but just a land development is being done there.”

Shpinariov also said he doesn’t know who owns SP Soling, though he also heard that it could be Galanternik. Shpinariov said he held all the negotiations with SP Soling in the building of the City Council with mediation by the city authorities. “I’ve never seen Galanternik, I’ve never met him,” he said. The first part of the Summer Theater’s reconstruction is planned to be finished on June 1.

Political plans

On May 7, a group of activists made a public address to president-elect Volodymyr Zelenskiy, asking him to ensure a proper investigation of attacks on them and bring new faces to the city and oblast. The new president is supposed to appoint a new person to the currently vacant office of the Odesa Oblast governor after Maksym Stepanov was sacked from his post by President Petro Poroshenko on April 10.

Mykhailo Kuzakon, leader of the Narodny Rukh of Ukraine party in Odesa, told a press conference that now all the branches of power in the city “serve the clan of Galanternik-Trukhanov” but not the local residents. “The first steps of the newly elected president will show if he plans to make changes in the country or not,” Kuzakon said.

On April 15, Trukhanov admitted in an interview with the Livy Bereh website to having “good human relations” with Zelenskiy. Zelenskiy’s Kvartal 95 production studio has held concerts and shot videos in Odesa seaport in recent years.

Trukhanov also admitted in an interview to having good relations with Ihor Palytsia, the former governor of Odesa Oblast and a loyalist to oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, who has a business partnership with Zelenskiy. Trukhanov said he plans to campaign for re-election as a mayor in 2020.

Mykhailyk, who also plans to campaign for mayor, said it’s unclear whether Zelenskiy will support Trukhanov’s clan. “We will demand that Zelenskiy appoint as governor a person with an untainted reputation,” he said. “If not, we will oppose him as we did Poroshenko.”