CHONHAR, Ukraine – Lieutenant Colonel Oleksandr Martinyuk, head of the Berdyansk border guard division, corrects sternly when he’s told that the Ukrainian checkpoint at Chonhar, in southern Kherson Oblast, looks increasingly like an international border crossing.

“It’s a temporary control point, and it really differs from an international border point,” Martinyuk said.

Later in our interview, he stumbled over what word to use for the bridge travellers cross between his control point and the opposite point.

“The dividing line,” interposed Major Nelya Dotsenko from the border guard press service.

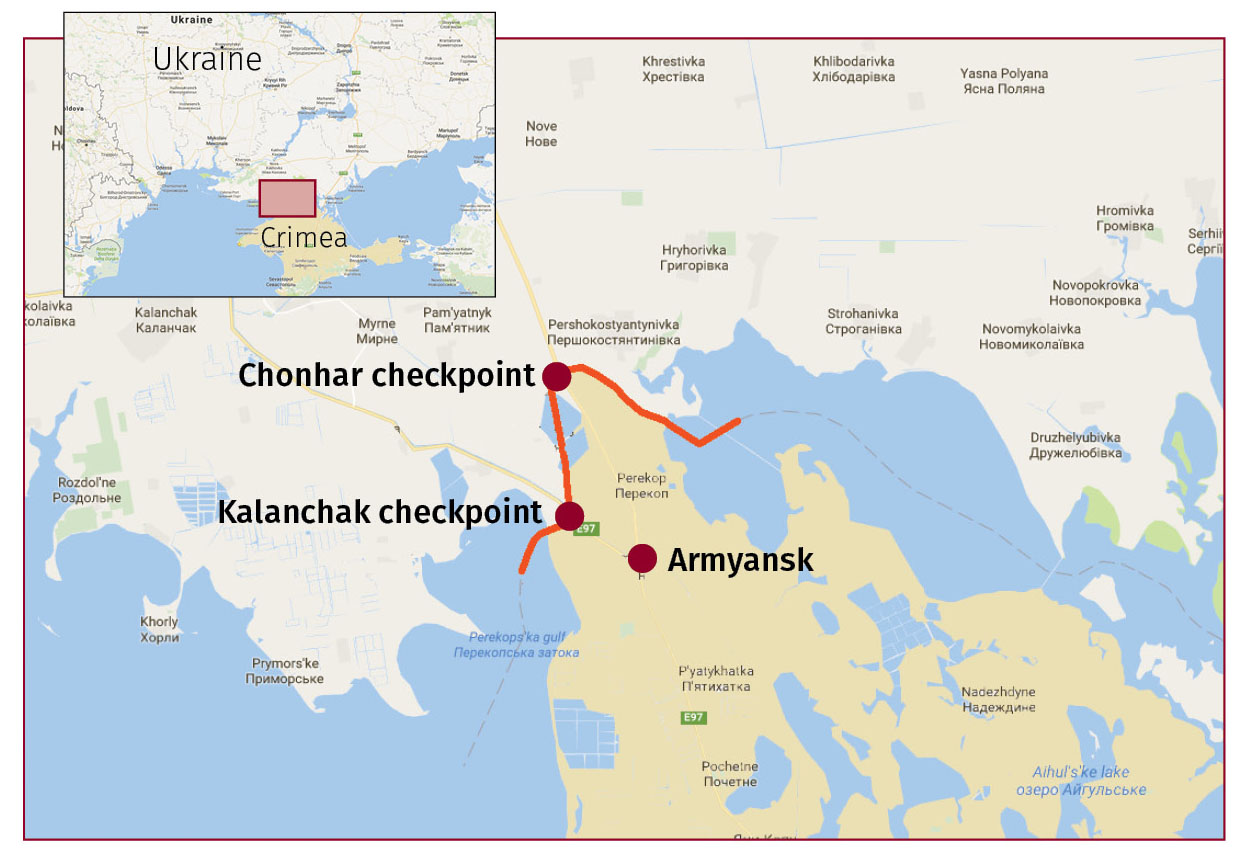

The Chonhar checkpoint, on one of three roads threading through sea inlets and acres of reeds, is on the linguistic and geopolitical line of division between southern Ukraine and Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula, currently occupied by Russia.

Chonhar is a small town of 1,400 people 763 kilometers south of Kyiv.

As far as Ukraine is concerned, passengers who queue to show their passports, open bags and car boots for customs inspection and, if they are not Ukrainian citizens, get a stamp in their passports, are crossing an administrative line.

On the other side of the bridge, the words “temporarily occupied” elicit a snort of amused contempt from Russian security service officers. Here, all signs indicate an international border crossing, and the only official mainland is Russia.

In the more than two years since Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine, the Chonhar crossing checkpoint has developed from concrete blocks, temporary tents and shacks, and chaos.

But the cognitive confusion remains. Passengers refer to 2014’s annexation as “a revolution,” “events,” or just “everything.” For those queuing with their passports and bags, this is a border with all the concomitant extra time, expense and stress.

Trains connecting Crimea and the Ukrainian mainland stopped running in late 2014. Cars with new Crimean number plates are not allowed back into Crimea from the Ukrainian side. Passengers must cross the bridge, the “dividing line,” on foot.

The Ukrainian border guard service has increased personnel, built a covered walkway for pedestrians, and put up a shelter housing a chemist’s and small food kiosks to make the wait more bearable.

There is a 24-hour hotline and an online webcam showing checkpoint queues. These additions were introduced to combat disinformation from the other side, according to Martinyuk.

“The occupying forces inform people in Crimea that there’s no power on our side or our technical equipment doesn’t work,” he said. “When they get to our checkpoint we have to do a lot of explaining that in fact everything is fine.”

On the other side, the Russian border point is far larger. Instead of the cafes and chemists, there are numerous small offices for interviews and “special checks” of suspicious passengers – which included myself. I didn’t apply for permission to write about the Russian border control point, so didn’t feel I could ask about Martinyuk’s claim of disinformation, although during the 90 minutes I was detained there I had plenty of time to.

At the Ukrainian checkpoint, all those queuing to go to Crimea who agreed to speak said they were making regular trips to relatives or friends. They lamented the changes that meant they had to take three or four different forms of transport – paying each time – and stand in the cold, instead of riding a single bus or train smoothly to their destination.

“What can you do, it doesn’t depend on us,” said Lyubov Zholud, a pensioner from nearby Novotroitsky district. Her son and his family live in Yalta on the south Crimean coast, and have not been to see her since the border was imposed, she said.

Zholud was lugging bags of home-grown duck, cheese and sour cream for her grandchildren. But she was stopped at customs; since Ukraine imposed an official blockade in late 2015 such products are restricted, as Olga, 59, on her way to visit her parents in Crimea, already knew.

“I have my own smallholding and now I can’t even take them a chicken,” she said. Olga makes the tedious, unpredictable trip from her home near Zaporizhya once a month; in summer, when passengers can number up to 6,000 a day, she has to wait much longer in queues.

I asked if her parents had thought of moving to mainland Ukraine after annexation. “Oh no,” she said. “They get a good pension there. Here they’ll have just a small pension, and they don’t want that.”

Olga, like most people there with relatives in Crimea, refused to give her last name or say where exactly her parents lived, “in case it causes problems.”

Although the buffer area seemed calm this week, Russian authorities in Crimea recently arrested three men in Crimea, claiming they were spies for Ukrainian armed forces; three similar arrests took place last summer after Russia alleged an “armed terrorist incursion” into Crimea from the Ukrainian mainland.

Meanwhile, a year ago, Ukrainian nationalists and Crimean Tatar activists who oppose the annexation of their homeland cut off electricity supplies to Crimea and imposed an illegal goods blockade at Chonhar and the two other crossing points, searching and detaining travellers without a warrant and confiscating goods.

The goods blockade is now legal, and official signs list what cannot be transported – including meat, dairy, flour-based products and anything intended for sale.

Crimean Tatar activists (from Crimea’s ethnic minority) have formed a legal civilian group Asker, subordinate to the border guards, with three volunteers on daily duty at Chonhar to provide assistance to travelers and “keep civil order,” Martinyuk explained.

Asker’s most valuable contribution, he said, was countering disinformation from the other side about problems crossing into the Ukrainian mainland.

“They’re from Crimea, but they’re here and can see what is going on, so they explain to their fellow Crimeans that it’s not really (a problem),” he said.

The volunteers also provide advice to Crimeans coming to the mainland to receive or renew Ukrainian passports, or get Ukrainian birth certificates for children born post-annexation. Crimeans cannot travel with Russian passports issued in Crimea, as most countries still consider them Ukrainian citizens.

When I asked the Asker volunteers if they still cooperated with Ukrainian nationalists like Right Sector, who publicly supported the illegal blockade but just as publicly left when it was legalized, one gestured to a side road where a Right Sector flag fluttered from a bus shelter.

“They’re still here, but not with us,” she said. “They’re doing their own thing.”

For Asker volunteers from Crimea, and for border guards like Nelya Dotsenko who served in Crimea before 2014, work here on the ‘dividing line’ is personal duty.

“There are no nationalists here; there are concerned patriots,” said Martinyuk. “Crimea is Ukraine, and we are for a united Ukraine and a united people.”