Valentyna Simonenko, a nominee for the new Supreme Court, registered as a Russian taxpayer in Russian-annexed Crimea in 2015, according to the official register of Russia’s Federal Tax Service checked by the Kyiv Post.

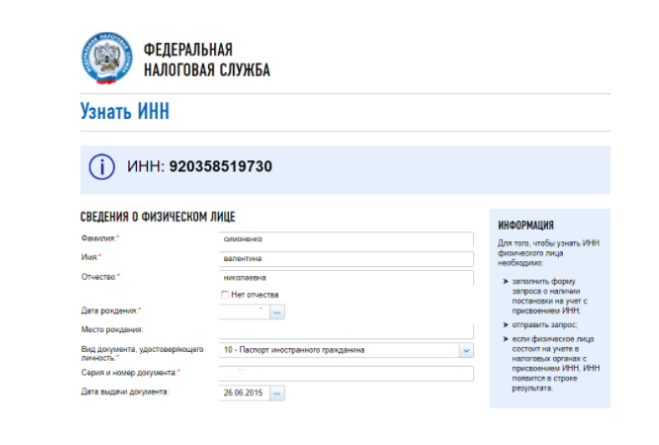

A screenshot of the Federal Tax Service’s entry on Simonenko was published on Feb. 2 by the Public Integrity Council, a civil society watchdog.

The Presidential Administration could not comment immediately. Oksana Lysenko, a spokeswoman for the High Council of Justice, told the Kyiv Post the council would check the information.

Simonenko, head of the Council of Judges and a judge of the old Supreme Court, registered in the Russian-occupied city of Sevastopol, according to the screenshot.

“By appealing to the illegal occupation authorities and assuming legal obligations before the aggressor country, she effectively recognized the jurisdiction of Crimean occupation authorities and agreed to pay taxes to the aggressor country’s budget, at whose expense the war against the Ukrainian people is being waged,” the Public Integrity Council said in a statement.

The Public Integrity Council said that Simonenko had been lying when she claimed in an interview at the High Qualification Commission in May that she had not contacted Russian occupation authorities in Crimea in any way.

According to the Ukrainian law on Russian-occupied territories, any interaction between Ukrainian officials and the occupation authorities is banned, they said.

The Public Integrity Council added that Simonenko’s registration as a Russian taxpayer could be linked to her possible efforts to avoid declaring property in Russian-occupied Crimea and to continue bussiness activities there.

Simonenko claimed in response to the information that she had been automatically registered by Russian occupation authorities based on her pre-annexation status on Crimea without being aware of it.

Roman Maselko, a member of the Public Integrity Council, refuted Simonenko’s claim, saying that the site of Russia’s Federal Tax Service shows that she used her post-annexation Ukrainian passport issued in 2015 to register as a taxpayer in Russian-occupied Crimea.

The Public Integrity Council on Feb. 2 held a protest urging President Petro Poroshenko not to appoint Simonenko to the Supreme Court.

A screenshot from the register of Russia’s Federal Tax Service on Valentyna Simonenko.

The High Council of Justice on Dec. 28 approved the appointment of Simonenko to the new Supreme Court. Her credentials have yet to be signed by Poroshenko.

Simonenko’s candidacy was vetoed by the Public Integrity Council. However, the veto was overridden by the High Qualification Commission and ignored by the High Council of Justice.

Her sister serves the Russian occupation authorities in Sevastopol as an official, while her ex-husband had business ties to the occupied territories while they were still married, and she visited the areas after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the Public Integrity Council said. Simonenko argued that she disagreed with her sister on politics and that she had nothing to do with her ex-husband’s activities.

Simonenko has also criticized judicial reform, lambasted Serhiy Bondarenko, a whistleblower judge pressured by his boss, failed to punish judges who persecuted EuroMaidan demonstrators, lashed out at electronic asset declarations, and criticized the National Anti-Corruption Bureau, the Public Integrity Council said. Simonenko argues that she has done everything in her power to help whistleblower judges and punish those involved in political cases.

She has failed to declare firms owned by her ex-husband but said he had not informed her of them.

As many as 30 discredited judges deemed corrupt or dishonest by the Public Integrity Council were nominated for the Supreme Court by the High Qualification Commission in July, and 29 of them were approved by the High Council of Justice in September to December. Poroshenko has already appointed 27 of them to the Supreme Court.

The Public Integrity Council said in October that it had “grounds to assume that the (recent Supreme Court) competition was rigged” by the High Qualification Commission and the High Council of Justice so that it would appoint politically loyal candidates. They denied the accusations.

Meanwhile, High Council of Justice Chairman Ihor Benedysyuk, Benedysyuk was simultaneously a judge of a Russian court martial and a Ukrainian one in 1994, according to his official biography on the council’s site. Public Integrity Council members say that Russian citizenship was a necessary precondition of being a Russian judge, and that his appointment as a judge of Ukraine was illegal if he had Russian citizenship or was not a Ukrainian citizen.

If Benedysyuk is a Russian citizen now, he does not have a right to hold his job.

Benedesyuk claimed on Feb. 2 that he had received his first Ukrainian passport in 1996 and had never had a Russian passport. If true, that still leaves the questions of how he could have been appointed to a Russian court without being a Russian citizen and whether he was a Ukrainian citizen when he was appointed to a Ukrainian court.