As Kyiv shut down its public transport for almost all of April, hoping to curb the spread of coronavirus, millions of Kyivans suddenly had no affordable way to get to work, see a doctor, or visit elderly family members.

Only workers in critical industries, who could obtain a special permit from the government through their employer, were allowed to use public transport.

But the rules were easy to bypass, as scammers flocked to social media, offering fake permits and promising they would work. Dozens of users reported that they had no problem using all public transport, including the metro, with the permits sold online.

The Kyiv Post looked into online offers and their possible illegal connection to Kyiv’s hospitals.

As desperate Kyivans applauded the sellers for helping them through difficult times, scammers seized the opportunity and made a buck.

Opportunity

Immediately after the lockdown began on April 5, social media accounts with offers to sell “real” transportation permits started to appear.

One could find scammers simply by searching “permit” in Ukrainian or Russian.

Just on Instagram, the Kyiv Post found over 30 accounts, while popular messaging app Telegram had over 5 channels where people offered to sell permits.

The demand was as high as the supply: some Instagram posts had over 30 comments by people asking about prices.

The cost ranged from Hr 150 to Hr 250, with same-day delivery by a courier, or by the popular Nova Poshta delivery service.

Earlier in Feb., the Kyiv Post reported about scammers who sold counterfeit negative COVID-19 test results, using Nova Poshta as well.

The company’s press service said their employees cannot check the authenticity of documents delivered through Nova Poshta and aren’t responsible for the scam.

Read more: Fake negative COVID-19 test results sell openly in Ukraine

All scammers claimed that their permits were authentic and wouldn’t alarm transportation workers or the police.

The permits on sale had the seals of different enterprises, including large store chains like Silpo and Epicenter K.

But fake seals are also openly sold on the internet and regularly used by people who sell fake documents ranging from doctors’ notes to certificates of good conduct.

Almost every account also cautioned against their fellow scammers.

“There is too much fraud surrounding the selling of permits,” one Instagram account said. “Remember, a (real) permit has a reflective engraving and is issued with a real seal.”

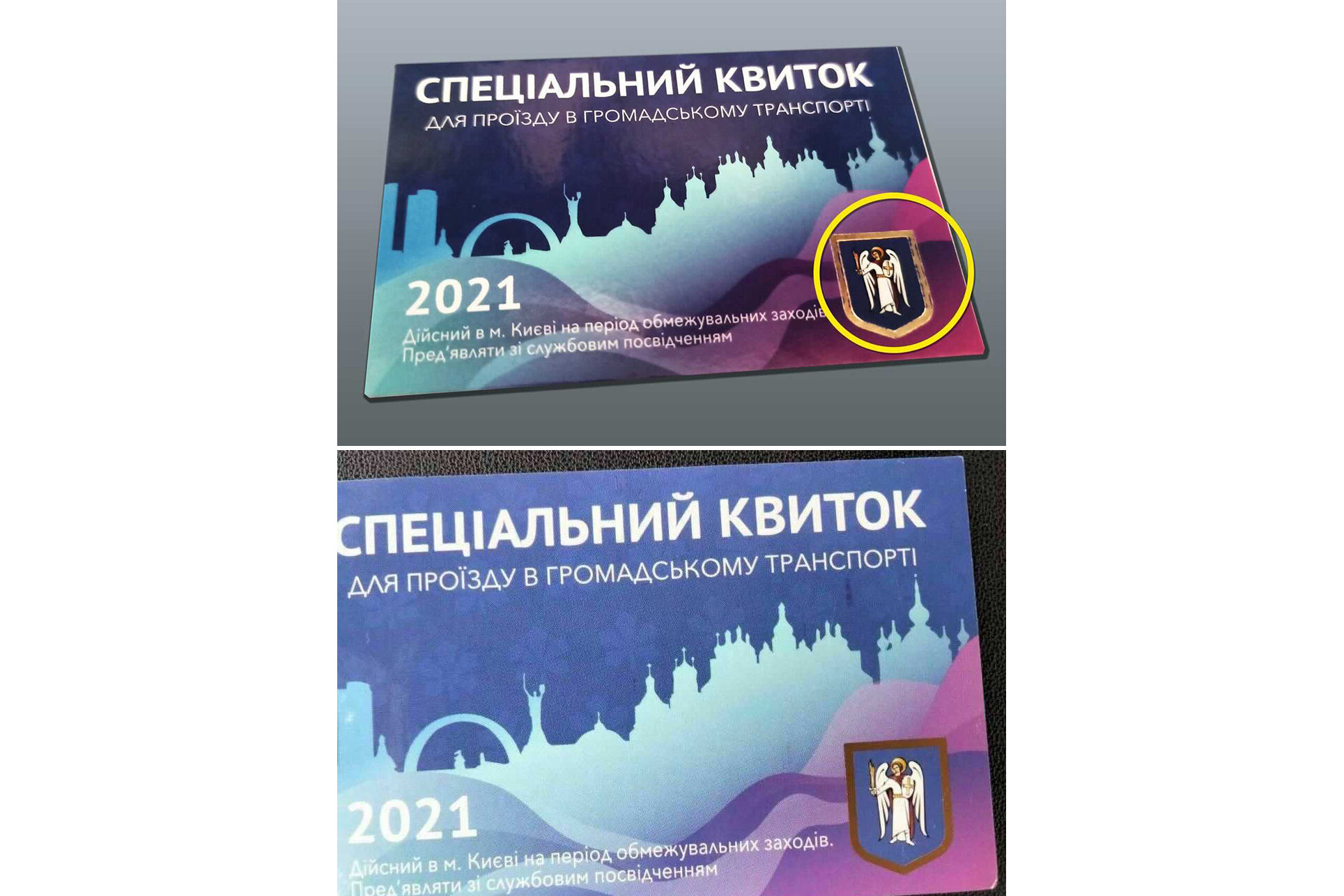

Top: A screenshot made by Ukraine’s broadcaster Suspilne — a real transport permit issued by the government, with the Kyiv Coat of Arms surrounded by a gold engraving, circled in yellow.

Bottom: A permit sold by scammers online, which looks identical to the real permit.

Indeed, a permit issued by the government has a gold engraving around the Coat of Arms of Kyiv, which is located in the lower right corner of the permit.

An authentic government-issued permit also has the seal of the individual’s workplace, as well as a signature of the company’s manager.

Documents offered for sale online appear identical to real permits, and have the golden engraving which would disappear if permits were fake and reprinted.

This means that they could have been smuggled through official channels.

Clinics involved?

A person behind the largest Telegram channel, which had over 3,700 followers, claimed that they were getting the permits in large quantities from a hospital. Hospitals, including private ones, qualify for permits as essential businesses.

Hence, the scammers demanded an upfront payment to “pay the chief physician.”

The scammers didn’t specify the name of the hospital, but later posted photos and videos of the permits which had seals of Kyiv City Heart Center and the adjacent Kyiv City Ambulance Hospital.

Sellers also offered certificates of employment from hospitals and other enterprises, to prove the permits’ authenticity.

The certificate of employment, supposedly obtained from the Kyiv City Heart Center, had the name of an alleged chief of personnel, one Shkliar S.P., but didn’t have a signature.

In reality, the deputy director-general for personnel and social affairs at the Heart Center is Halyna Kostiushko.

In a comment for the Kyiv Post, she denied any connection between the hospital and the scammers.

“I am the only one who signs off on the certificates of employment,” Kostiushko said. “We document every certificate we issue in our database.”

The Kyiv City Ambulance Hospital employment certificates had the name of Oleksandr Shved as their head of personnel.

Shved does work at the hospital, and according to Ukraine’s news broadcaster Suspilne, declined to comment about the permits. He also added that the staffer who might have signed certificates that were sold online was not at work because his shift was over.

The Department of Health of the Kyiv City State Administration said it’s already looking into the incident, Suspilne reported.

A municipal transport worker checks for special permits for public transport in Kyiv on April 5, 2021. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Another hospital whose name popped up on the permits and employment certificates was Boris Medical Clinic, one of the best-known private health care providers in Kyiv.

These employment certificates also had the name of the supposed chief of personnel, Rublenyk B.B., as well as the clinic’s seals.

But, since Boris Medical Clinic recently became a part of the larger health care network Dobrobut, it no longer uses Boris seals, the clinic’s information operator told the Kyiv Post.

Another Instagram user claimed they were a Boris employee named Iryna, who obtained permits from the clinic’s administration.

“Since our clinic laid off over 40% of their staff, we have an abundance of permits… the administration let us sell them to those who truly need them to get to work,” the user wrote.

Dobrobut, which now oversees Boris Medical Clinic, hasn’t replied to the Kyiv Post’s request for comment.

Desperation

Ukrainians who seek to obtain the permits illegally seem angry and desperate, as many are unable to get to their jobs, care for family members who live far away, or even get to a hospital.

“How do I get to see a doctor? How do I help my elderly family members?” user Olga Sosnova commented under a post in Telegram.

“I am grateful there are people who aren’t afraid and who help us… together we are strong,” she added, referring to the scammers.

Taxis were among the few transportation options left to people without permits. But taxi prices soared due to high demand.

“Unfortunately, not everyone can take taxis,” another user wrote.

Bureaucracy

The process of obtaining the permits from the Kyiv City Council was arbitrary and had bureaucratic hurdles.

Some employers reported receiving only a portion of all the permits they’ve applied for. Meanwhile, some non-essential businesses were able to get permits as well.

“Not all our staff received the permits, including me, so I just had to stay home and wasn’t able to work,” Valentyna Eremina, who works at a state agency in Kyiv, told the Kyiv Post. She initially wanted to buy a fake permit, but changed her mind, fearing scammers would just steal her money.

“I live on the left bank (of Kyiv), but my job is on the right bank. Metro was the main method of transportation for me,” Eremina said.

Rules for all?

Although the transportation ban was meant for all types of public transport, not all drivers were willing to follow the rules.

Drivers of marshrutkas — routed shuttles that originated in Soviet times — appeared to be willing to transport anyone without a permit.

“They let you in and don’t ask anything, as long as you pay,” Julia Karakai, a Kyivan who uses marshrutkas regularly, told the Kyiv Post.

Karakai thinks that drivers disobey because marshrutkas are operated by private companies, which lose significant profits during lockdowns.

People get off a marshrutka in Kyiv on Sept. 2, 2020. (Volodymyr Petrov)

Even before the lockdown, the Association of transport carriers of Kyiv and Kyiv oblast asked the Kyiv City Council to officially shut down marshrutkas while Kyiv was in the red zone. During this time, public transport was instructed to operate at half capacity.

“Carrying 11 passengers is very unprofitable for us,” the association’s head Ihor Moiseenko said.

As the transportation ban entered into force, photos of marshrutkas carrying only two to five people circulated on social media.

The metro, on the other hand, was often patrolled by the police, who made sure people had government-issued permits and identification documents upon entry.

Some Kyivans were caught carrying fakes and were turned away.

Kyiv City Council announced the transportation ban will be lifted on April 30.

Nevertheless, scammers continued to offer fake permits, deceitfully telling social media users that lockdown will be extended until May or June.

“Tomorrow, lockdown will be extended at least until May 10. Message us for purchase…”