The Azov has become a lawless sea, and Russia is to blame.

That’s the conclusion many are drawing after two merchant ships under U.S. sanctions, linked to the illicit transportation of fuel to Iran and Syria, burned near the Kerch Strait from Jan. 21 to Jan. 23.

But despite growing international concerns about safety, Russia refuses to allow an international monitoring mission into the region and was also unwilling to discuss such a plan with Ukraine.

Observer mission denied

Kremlin officials, who previously said they would allow German and French observers to form an Azov Sea monitoring mission, backtracked on Jan. 22, saying there would be no such agreement.

Instead, Moscow will only allow a one-time visit from German and French experts, Russian officials said, adding new credibility to accusations that Russia is only interested in continuing its illegal annexation of the Azov and tightening its grip on the strategic Kerch Strait.

In December 2018, Russia also rejected a German proposal to deploy observers from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, or OSCE, to the Azov.

The latest announcement from Moscow comes amid heightened concerns over freedom of navigation through the strait and sea, violations of international law, and maritime safety.

Smuggling ships ablaze

On Jan. 21, the merchant ships Candy and Maestro, which sail under Tanzanian flags, anchored near the Kerch Strait. Suddenly, an explosion rocked one of the ships, setting them both on fire.

Soon, it became clear that one of the ships had been transporting a cargo of liquid petroleum gas, or LPG, to the other. The explosion was the result of a dangerous ship-to-ship transfer that reportedly took place in shallow, rough waters close to the Kerch Strait. Additionally, both ships had reportedly turned off their tracking devices, a common practice when illicit shipping or illegal activity is taking place.

Russia reportedly encourages shipping companies to switch off their satellite tracking systems — despite the safety risks — in order to avoid detection and sanctions if they dock in Kremlin-occupied Crimea or transport fuel between Russia and sanctioned countries such as Iran and Syria.

According to U.S. treasury documents cited by the Financial Times newspaper, both of the ships that burned near the Kerch Strait have been used to illegally transport fuel between Russia, Iran, and Syria in defiance of sanctions.

At least 14 sailors have died and six remain missing since the blast. Emergency responders rescued 12 sailors from the burning ships. On Jan. 24, aerial photos showed that the charred vessels continued to burn, but emergency responders had begun to bring the blaze under control.

Andrii Maschenko, an expert on maritime law from Mariupol and managing partner of the Kyiv-based law firm MBLS, says that Russia’s past and current “illegal activities” in the Azov Sea and Kerch Strait have created a lawless and dangerous situation.

“Given the current conditions, unfortunately, we cannot say that navigation through the Kerch Strait and Sea of Azov is safe,” he told the Kyiv Post on Jan. 24.

A Tanzanian-flagged gas tanker burns after an explosion in the Black Sea near the Kerch Strait on Jan. 21, 2019. (Kerch FM)

A strangled sea

On Nov. 25, the Russian coast guard seized three Ukrainian navy boats and detained 24 sailors in Black Sea international waters off the coast of Crimea and near the Kerch Strait. But that attack was hardly the beginning of Moscow’s sea offensive.

Legal analysts and Azov Sea observers are quick to point out that the Kremlin’s aggressive, expansionist actions there began as far back as 2003, when Russia started constructing a sea dyke that would prove to be an earlier incarnation of its long-desired bridge connecting the Crimean peninsula to mainland Russia.

At the time, Russia said the dyke was needed to protect its beaches from erosion. In the years since, multiple skirmishes and clashes took place in the Azov Sea, including one incident in 2013 in which two Ukrainian fishermen were killed, as Russia moved to assert its control over the area.

But the Kremlin truly began blocking Ukrainian access to the Azov in May 2018, shortly after it opened its new bridge to the now-occupied Crimean peninsula.

“The construction of the Crimean Bridge, and further detention of merchant vessels sailing towards Ukrainian Azov Sea ports, just worsened the situation… Russia’s unfriendly actions started long ago,” said Maschenko.

Since May, Russia’s long campaign of harassing Ukrainian and international vessels has delivered a serious blow to commercial shipping. Companies and ports say they are losing millions of dollars.

In 2018, Ukraine’s Azov Sea ports of Mariupol and Berdiansk received about 6.6 million tons of goods. Should Russia blockade the sea entirely, the ports will face annual losses of up to $2 billion, experts say.

But according to Maschenko, who cites statistics from the Sea Ports Administration of Ukraine, valuable transshipments of coal, grain, and ferrous metals from Mariupol and Berdiansk, previously substantial, have been “constantly decreasing” since Russia began its war against Ukraine in 2014.

Blockaded ports

“The ports are pretty empty,” British member of parliament John Whittingdale told the Kyiv Post, after his Dec. 22 fact-finding visit to the Azov region.

“In Mariupol, we saw one ship being loaded, but were told it was likely to be stopped for at least 15 days waiting for checks (by Russian authorities) – even though there’s no legal basis for that,” he added.

Today, exports from Mariupol and Berdiansk — two ports that, according to the estimates of some experts, were responsible for 30-40 percent of the country’s steel exports — are negligible, while industrial production and output throughout the region is also down.

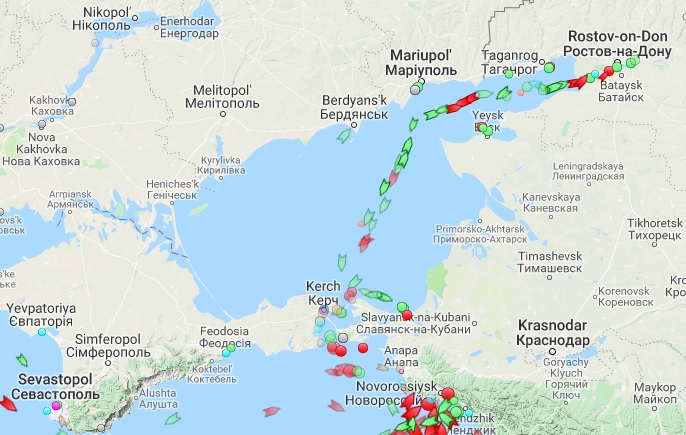

Live satellite photos confirm that Ukraine’s commercial shipping in the Azov Sea is all but crippled.

The live maps paint a bleak picture, showing that Berdiansk and Mariupol are almost empty of cargo ships, with only a handful of docked vessels and practically no shipping traversing the Azov to or from Ukrainian ports. At the same time, dozens of ships stream into and out of the Russian Azov ports of Taganrog and Rostov-on-Don.

To keep exports alive, Mariupol and Berdiansk have been increasingly reliant on Ukraine’s overburdened and outdated railways to get at least some of their goods to other ports, such as Mykolaiv or Odesa, more securely located with access to the Black Sea.

However, train cargo from Mariupol or Berdiansk must currently pass through Volnovakha, some 30 kilometers south of the Russian-held city of Donetsk and a 10-minute drive from the warzone.

If Russia wanted to, it could block Mariupol’s exports on land just as easily as it has crippled them at sea.

A Jan. 18 screenshot from MarineTraffic, a wesbite that uses sattelite data to track ship movements, shows the lack of activity around Ukraine’s Azov Sea ports of Mariupol and Berdiansk but a steady stream of marine traffic to and from Russia’s Azov ports at Rostov, Yeysk and Taganrog.

Investing in resilience

Ukraine’s international allies are slowly taking notice of the Azov region’s vulnerability, on land as well as at sea, even if they have not taken any robust measures against Russia – such as passing new sanctions – since the Kremlin stepped up its aggression.

To them, aid spending and strategic investments into infrastructure and industry, in order to protect Mariupol and Berdiansk from the effects of Russian blockade, could be an effective method of support.

In a Dec. 22 interview with the Kyiv Post, Michael Fallon, a senior British lawmaker of the U.K.’s governing Conservative party and secretary of defense from 2014 to 2017, said that Russia was breaching “all international law” in the Azov Sea while waging “economic war” on Ukraine.

He also said that he was disappointed to see European sanctions on Russia continued, but not increased. But there are other ways for the international community to help Ukraine, he suggested.

“I think we ought to be looking at how our international aid money is spent in Ukraine,” he said, adding that Ukraine’s southeast, especially Mariupol, is “extremely vulnerable” to economic pressure from Russia.

U.K. lawmakers Fallon and Whittingdale said that Ukraine’s international partners should be reviewing their aid expenditure programs and investments in the country, especially in the troubled Azov region, to determine how its “resilience,” particularly in infrastructure and transport, can be boosted.

According to some experts, a logical and highly desirable investment would be a fast, direct train connection that covers the roughly 150 kilometers from the coastal Azov city of Mariupol to Zaporizhia or Dnipro, cities some 500 kilometers from Kyiv with safe access to the Black Sea.

Whittingdale said that more British lawmakers would soon be coming to Ukraine’s southeast regions on similar research trips. But the European Union and European Investment Bank, or EIB, might be the first in committing to invest.

“The European Union and EIB and are sending a joint fact-finding mission to the Azov region and Mariupol at the end of the month, in order to assess areas of investment and funding” EIB spokesperson Anna Honcharyk told Kyiv Post on Jan. 24, adding that both the EU and EIB wanted to “expand their economic presence” in the region through investments and grants.