Ukrainians who won a revolution three years ago put justice high on their list of demands.

They are still waiting for results.

In a nation stunted by corruption and impunity, Ukraine still has not brought anybody to justice for multibillion-dollar plunder, bank fraud, mass murders and other high crimes.

But Oleksiy Filatov, the deputy head of the Presidential Administration in charge of judicial reform, told the Kyiv Post in an interview that help is on the way. If everything goes as planned, Ukraine will have a newly constituted Supreme Court by June.

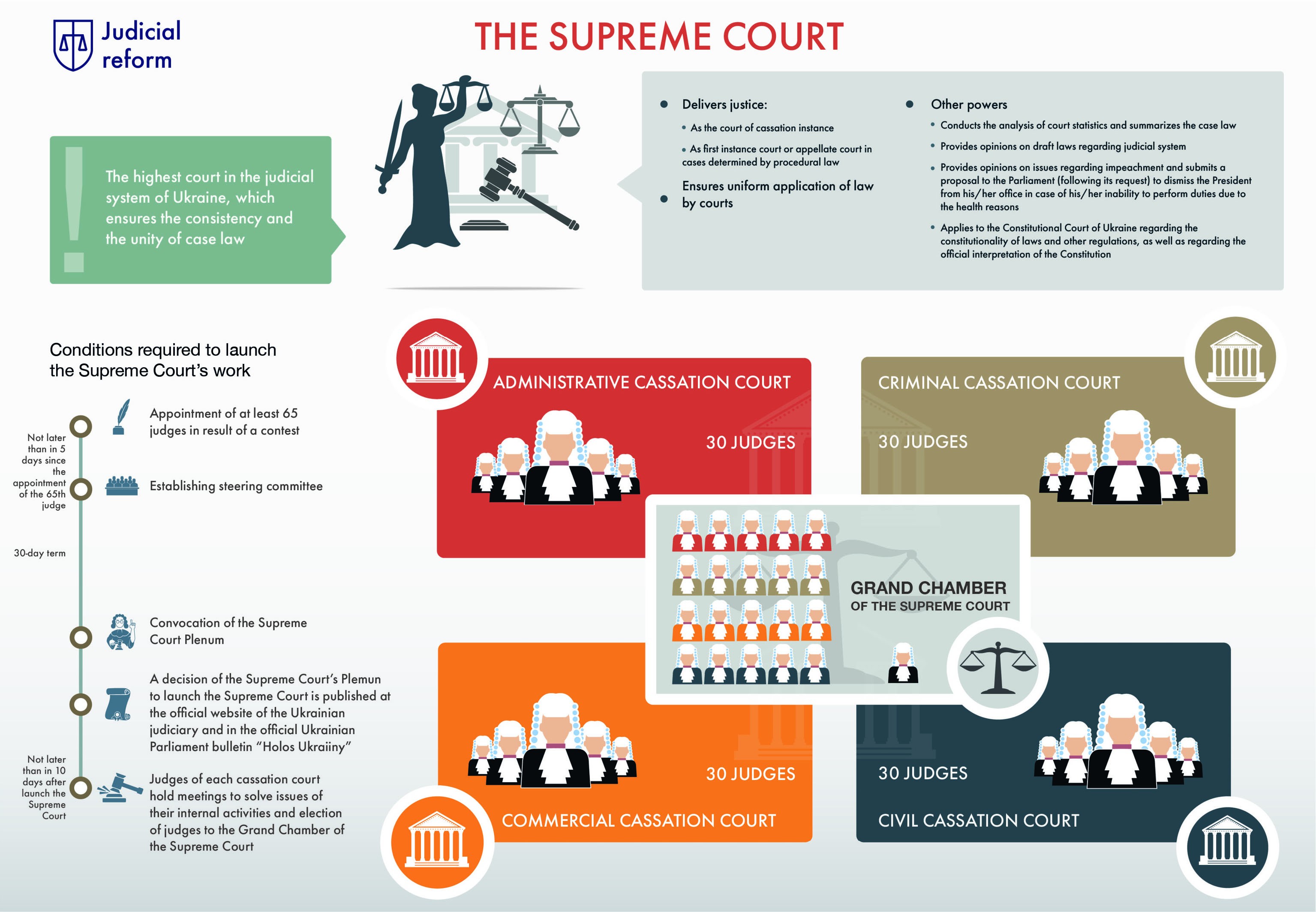

A competition is under way to choose 120 of the 200 judges who will eventually be seated, while 65 is the minimum number of judges needed to make the Supreme Court functional, Filatov said. Ukraine has so many Supreme Court court members because they include four specialized higher appeals, or cassation, courts that last year heard at least 170,000 cases, he said. Overall, the nation has 6,200 working judges.

“I believe the new Supreme Court will be far better than any court we had before,” Filatov said. “And if we are successful at forming this Supreme Court then we can count on dramatic change in the whole judicial system.”

For starters, the new Supreme Court judges will be paid Hr 200,000 ($7,381) monthly – a respectable income designed to discourage bribery.

The judges will have been chosen by the High Qualification Commission of Judges, which consists of no appointees of fugitive ex-President Viktor Yanukovych, ousted on Feb. 22, 2014, by the EuroMaidan Revolution, to Filatov’s knowledge.

And, through advisory bodies such as the Public Integrity Council, the selection process is transparent, Filatov said.

“We managed to make the rules of the competition as transparent as possible, even though we were criticized by the Council of Europe for having this competition too open, with too much participation by civil society. We managed to engage civil society to the extent nobody did,” he insisted.

But Filatov’s contention is disputed. For example, the selecting commission was supposed to publish online dossiers detailing the professional background, income and education of all candidates. To Filatov’s knowledge, the dossiers have been made public. Watchdog nongovernmental organizations say they haven’t – and those that have been made public are heavily redacted.

Moreover, while the selection process was open to lawyers and legal scholars in a bid to inject fresh talent into the courts, 78 percent of the 382 applicants were judges – casting doubt about how “new” and trustworthy the next Supreme Court will be.

When fully appointed, Ukraine’s Supreme Court envisions 200 judges who are the ultimate law of the land through its grand chamber. The four cassation courts act as higher appeals courts to lower court rulings. (Presdientail Administration)

No anti-corruption court

Even Filatov admitted that the new Supreme Court – even if consisting of top-notch legal minds with the highest integrity – won’t be enough.

The prosecutors, police, investigators, judges and defense attorneys who make up the legal system operate as “interconnected vessels,” Filatov said. “If you have dirty water in one of them, it’s inevitable it will make the water dirty in all the other vessels.”

And Ukraine’s got plenty of dirty water.

“I am not satisfied at all with what his happening in the judiciary in general,” Filatov said. “The general level in the judiciary is not satisfactory. The general level of the prosecution is still not satisfactory. All together, this makes an average criminal case have bad prospects. If there is a good defense lawyer, the prosecutor would not get a guilty verdict.”

Others have an even harsher view.

Besides the unreformed courts, Ukrainian law enforcement agencies such as the Interior Ministry, the Security Service of Ukraine and the General Prosecutor’s Office remain largely politicized, corrupt, ineffective and widely distrusted.

While new anti-corruption agencies have been established, they are understaffed compared to the traditional institutions and, even worse, they run into the same old discredited judges when trying to move cases through courts.

That’s why many Ukrainian reformers long ago called for the creation of a special anti-corruption court until the nation can restore public trust in the traditional institutions.

But creation of an anti-corruption court has stalled in the face of obstruction, inertia and disagreements. President Petro Poroshenko has yet to submit to parliament the administration’s proposal for such a court.

Reformist members of parliament such as Sergii Leshchenko and Yehor Soboliev believe that foreigners should preside over cases chosen for their gravity, but their proposed version faces opposition from the administration.

“My personal opinion is that we should have this court in place,” Filatov said. “The anti-corruption court can only build upon the fundamentals we put in place.”

The delays are taking place, he said, because the constitution first had to be amended, a law on the status of the judiciary had to be passed, a new supervisory High Council of Justice had to be chosen and changes had to be made to the legal powers of prosecutors.

Without these revisions, he said, a new anti-corruption court could not function.

“Our intention was to give up drafting to NGOs (nongovernmental organizations),” Filatov said. “Unfortunately, the draft law was not satisfactory.” He proposes a working group of experts to find agreement followed by a competition to select judges to “put this court in place.”

In other words, the establishment of any anti-corruption court with special powers remains a distant dream for Ukrainians even as impunity continues to flourish.

Critics want the anti-corruption court to be truly independent, instead of subordinate to the Ukrainian Supreme Court. But the constitution prohibits such extraordinary powers, he said, making the Supreme Court the highest law in the land.

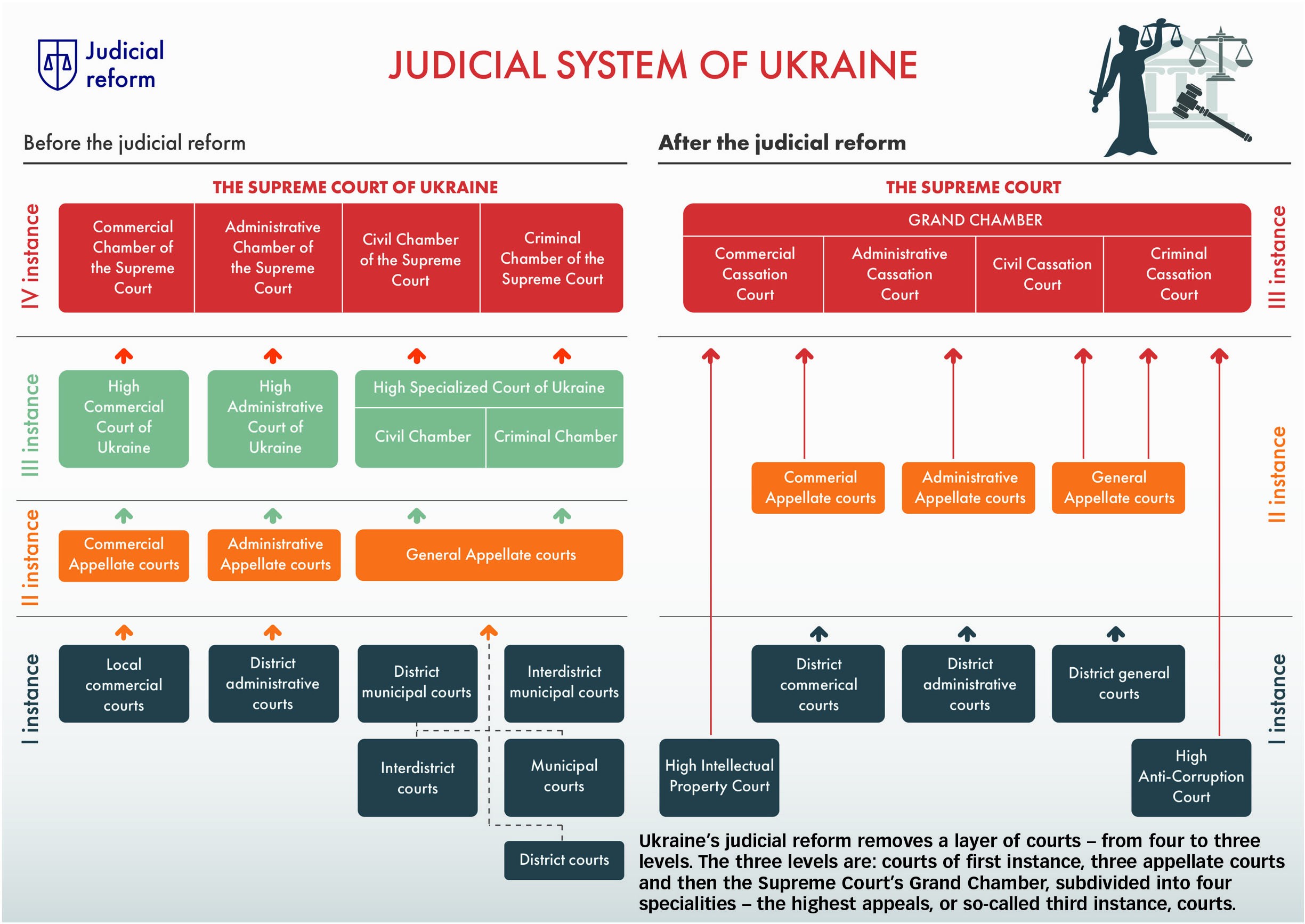

Ukraine’s judicial reform removes a layer of courts – from four to three levels. The three levels are: courts of first instance, three appellate courts and then the Supreme Court’s Grand Chamber, subdivided into four specialities – the highest appeals, or so-called third instance, courts.

‘Let’s see the results…’

The president, especially, but also the parliament have great influence by appointing commission members who choose the Supreme Court, raising the perennial question of political interference.

But Filatov rejects the premise.

“What makes you think that Poroshenko controls the Supreme Court?” he asked. “We are at now at a stage when Ukrainians don’t trust each other. There is certain political influence on the court system. The question is what is the extent of the political influence and does it interfere with properly executed justice. Political dependence has been one of the biggest problems in Ukrainian judiciary since long ago,” he said. “We are yet to see the results. The High Council of Justice was just recently reset, according to the new rules. The new Supreme Court is selected in a way to minimize political influence on the judges. Let’s see the results of the processes. Then we’ll be able to judge whether this process was successful or not. Then we will see whether there’s public trust or not.”

Private practice past

Filatov joined the Presidential Administration in 2014 after 13 years with Vasil Kisil & Partners law firm in Kyiv and more than 20 years as a private practice lawyer. His background partly explains his patience with Ukraine’s slow place.

“I had one of the biggest dispute resolution teams in Ukrainian law firms,” Filatov said. “I can tell you from very practical experience that the problems existing in the Ukrainian judiciary are not something you can change overnight. For the average person who probably hasn’t been to court anytime in his or her life and who sees only the surface, it’s easy to quickly judge and make a conclusion that we still don’t have a U.S. and U.S. standard court, which is true. The question is whether it’s realistically possible to make this kind of progress in three years.”

Some watching the reform under way contend Filatov’s powers are blunted by a criminal justice system that allegedly faces routine political interference from, among others, Poroshenko’s close ally in parliament, Oleksandr Hranovsky. The lawmaker, in interviews with the Kyiv Post, has denied his reputed status as “grey cardinal” controlling judges on behalf of the administration and its allies.

Filatov said he has only heard the rumors and read the news stories.

“Interference with the judiciary is a crime,” he said. “We will be able to say Hranovsky or anybody else has interfered with the judiciary as soon as there is a guilty verdict confirming this…I have heard rumors. I read the press. I did not receive a personal complaint.”

Oleksity Filatov, deputy head of the Presidential Administration in charge of judicial reform, looks on as President Petro Poroshenko signs papers during a March 22 session of the Judicial Reform Council in Kyiv. (Mikhail Palinchak)

Few jury trials

In many nations, political influence is lessened in a number of ways. One of them is jury trials. A jury composed of average citizens is empaneled and empowered to decide guilt or innocence, removing judges from the decision. Judges still preside over trials, but more as referees in deciding evidence to be considered and whether legal procedures are followed.

Ukraine’s constitution calls for jury trials, but in practice they are used in less than 1 percent of the cases, Filatov said.

“I would be happy to have jury trials in Ukraine,” Filatov said. But by and large, he said that Ukrainians still “don’t want to serve” as jurors.

“But this doesn’t mean we should abandon this idea,” Filatov said. “This idea and this tool will work effectively as soon as Ukrainian society is really ready for this. A jury trial can only be part of a very well working court system.”

But he also sounded skeptical, asking “how can we be sure a jury would not be bribed? How can we be sure a jury will not be influenced or intimidated or subjected to any other influence from outside the courtroom? We can’t be sure about the judge, too. But have now a very transparent procedure of appointment and liability if the judge takes a certain incorrect decision or violates certain procedural rules and so on.”

Distrusting ex-partner

Filatov’s former colleague, Andriy Stelmashchuk, managing partner of Vasil Kisil & Partners law firm in Kyiv, has no faith in the judicial reform under way.

“We have to replace those people who compromised themselves, not just to fire them, but to put somebody to jail, carry out an investigation with respect to people involved in illegal activities,” Stelmashchuk said. “Nobody was actually put into jail or accused, at least. We see some investigations with respect to a few people, but not enough.”

His assessment of Poroshenko’s motives and that of Filatov, the president’s point man, is scathing: “They are trying to create another court which will be controlled by the president,” Stelmashchuk said. “We didn’t have to have all those huge amendments to the legislation to change the judiciary. They took a lot of time. The purpose of the movements is clear: They demolished the old Supreme Court in Ukraine and created a new one. It’s a technical move…It’s an old trick used by all presidents.”

The fundamental problem, Stelmashchuk said, is that “there are no check and balances in Ukrainian politics.” Politicians have “convinced themselves” they are interfering in the judicial system “for the good of the nation.”

He doesn’t believe Poroshenko is acting in the best interests of the nation.

“He decided to go the way Yanukovych did. He’s much more clever than Yanukovych from an intellectual perspective. Politically, he’s repeating the same mistakes – son who is in parliament, how he behaves with oligarchs. It’s very disappointing.”

Filatov’s final word

While their emphasis is different, Stelmashchuk and Filatov aren’t all that far apart when it comes to the effectiveness of Ukraine’s judicial system.

But Filatov still has faith in the process he’s leading and said the administration has the nation’s best interests in mind.

“I am not satisfied with the quality of justice Ukraine has at this point,” Filatov said. “There are a number of instances which can be seen as examples as to how justice should work – good judgments, good prosecutors. But we still have too few examples. I want to have more.”

As for the pace, “I still think we could move faster, if not for the political situation and some obstacles that we don’t really influence,” Filatov said. “At the same time; I am pretty satisfied with what we have managed to achieve.”

President Petro Poroshenko’s 3 objectives for judicial reform from March 22 Judicial Reform Council meeting

1“To ensure independence of courts, independence from the political pressure. That is why we have abolished the function of the president and the Verkhovna Rada in the formation of the judicial corps to ensure this independence.”

2Responsibility of courts and judges.

3“Renew the judicial branch of power.”

Ukraine is “at the final stage of establishing the new Supreme Court,” Poroshenko said. “I am really hopeful that the new Supreme Court will soon start working to defend the right of Ukrainians to a fair trial. Society has an opportunity to control, as the key thing I expect is trust in the new Supreme Court and restoration of public confidence in the judicial power … We are speaking of a country with the rule of law, not the rule of crowd.”