Ukrainian politicians are heading back into parliament from vacation season on Sept. 5. But it’s not going to be an easy return as the new session will bring a lot of work for lawmakers.

The government is hoping for passage of 50 pieces of legislation, including key proposals — some languishing for months and years — to move the nation ahead in its transformation from Soviet republic to a democratic, market-oriented nation.

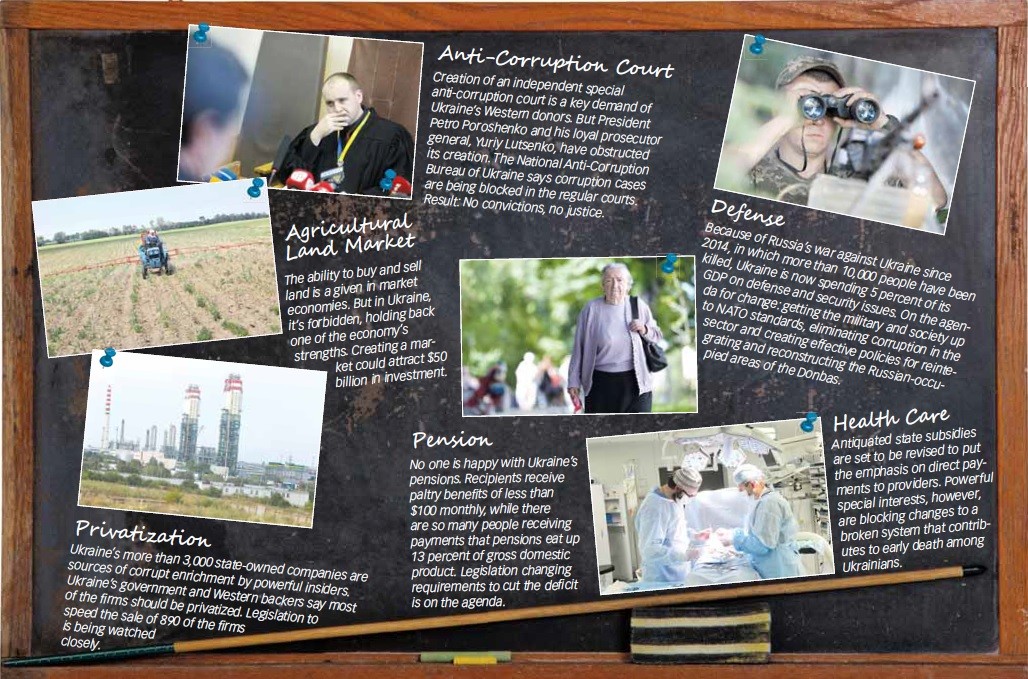

Before the Verkhovna Rada went on vacation on July 14, lawmakers failed to finish the healthcare and pension reform, approve the creation of agricultural land market, speed up the privatization of state-owned enterprises, create the anti-corruption court and much more.

Some of the mentioned reforms are needed to maintain cooperation with the International Monetary Fund. The IMF has already allocated $13 billion out of the $17.5 billion bailout program for Ukraine agreed in 2015.

But the fund suspended lending in April due to stalled reforms in Ukraine. Lawmakers approved only one bill of the two needed to launch healthcare reform, postponed land reform indefinitely again, and failed to pass laws to upgrade Ukrainian schools to international standards.

Although the Ukrainian government has been promising to recognize the conflict in the Donbas as a full-fledged war with Russia, and not an anti-terrorist operation, for a couple of years already, Ukraine’s Security and Defense Council chairman Oleksandr Turchynov promised to present the bill on that in Rada only this fall.

The government has already signaled that working on improving the business climate, the effective management of state property, privatization, state finance management, energy, law enforcement and defense will be major themes.

Ukraine’s parliament returns on Sept. 5 after a long summer break. It remains to be seen whether the lawmakers move on long-stalled or obstructed reforms. Plenty is at stake in success, including continued lending from the International Monetary Fund, the confidence of private investors and the reputation of the nation.

Privatization

During the cabinet meeting on Aug. 30 Ukrainian Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman said the government hoped this fall the Rada would give the green light to the long-stalled privatization of more than 890 of the 3,000 state-owned enterprises in Ukraine.

Only state-owned companies that are strategically important for Ukraine’s economy would stay under government control. Others would be passed into concessions liquidated, or sold to private investors.

The new privatization law the government plans to present in the Rada this fall is to speed up the privatization process and protect the rights of foreign investors in Ukraine.

The privatization of state-owned enterprises was one of the IMF’s demands to continue cooperation under the bailout program agreed with Ukraine in 2015.

If the Rada approves the government’s bill during the fall session, it will speed up the process of privatization by cutting the time Ukraine’s State Property fund needs to prepare the state enterprise for sale to private businesses.

For example, the fund will be given one year instead of two to corporate the major enterprises, like Odesa Portside Plant fertilizer or the state alcohol producer UkrSpirt, for privatization.

Agricultural land market

Ukraine is one step away from becoming a Europe’s farming superpower, given that 70 percent of its territory is suitable for agriculture. However, the country has been unable to open its land market for sales for 16 years, which has hampered the development of the agricultural sector.

The existing moratorium on land sales also deprived the sector of credit: foreign investors are reluctant to invest and banks won’t provide loans, as land can’t be used as collateral. It also puts at risk another installment of the IMF loan.

First introduced in 2001 for three years, the moratorium has been extended every year since. The current ban expires on Jan. 1, and this fall the

Verkhovna Rada has to decide whether to lift it, or prolong it yet again. The main opponent of the land reform in the parliament is Yulia Tymoshenko’s 19-member bloc, Batkivshchyna, backed by the agrarian unions, who are afraid that farmland will be lost to foreigners and large agroholdings.

The Cabinet of Ministers has to come up with a model for a land market that would satisfy both parliament and farmers.

Healthcare

There are two key draft laws to be backed this fall that will help to transform Ukraine’s healthcare system.

A bill on state financial guarantees for medical services would help to reduce the practice of making unofficial private payments for medical services. Another bill would enable Ukrainians to choose from a list of primary care doctors, not dependeing on the place where they are registered as living, and with whom they will be required to sign a contract.

Officials hope that stimulating competition between individual care providers will drastically improve the quality of medical services and allow doctors to earn higher salaries of between $500–600 per month, as well additional bonuses for the services provided.

Ukraine’s budget currently pays for healthcare based on the size of inputs, for instance, the number of patient beds and the area of hospital rooms.

After the reform, medical institutions will be paid for based on contracts linked to output indicators, like the number of enrolled patients or the patient case mix.

Education

The new law on education is part of an overhaul of Ukraine’s current educational system. It includes introducing a 12-year school system to replace Ukraine’s current 11-year school program. If supported by parliament, children who start school in 2018 will enter a 12-year school program similar to ones already in place in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Schools will be able to form their own curricula, develop syllabi for school subjects in accordance with secondary education standards, and select textbooks and teaching methods. The law will also enable school students to choose between academic or profession-oriented subjects.

Anti-corruption court

The creation of an independent anti-corruption court as a final instance in the fight against corruption was another of the main demands of the International Monetary Fund.

Ukraine’s parliament failed to pass a special bill before the IMF’s deadline (mid-June) which would entail establishing anti-corruption courts by spring 2018.

According to Ukrainian law, President Petro Poroshenko was to have presented his own presidential alternative bill in a short term after.

His and General Prosecutor’s Yuriy Lutsenko’s idea of creating special anti-corruption panel of judges within the old court system of Ukraine generated a great deal of opposition from watchdogs and lawmakers,who created the draft law on setting up the anti-corruption court.

They said the panels would be highly influenced by the presidential administration.

On July 13, during the EU-Ukraine Summit in Kyiv, Poroshenko managed to persuade European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker that an anti-corruption court is not needed, just an anti-corruption panel in the regular court system.

“We previously insisted on the establishment of a new special anti-corruption court in Ukraine, but President Petro Poroshenko persuaded us that … it would be better to create a special anti-corruption panel of judges, who would convict high-profile corrupt officials in Ukraine,” Juncker said.

In May Poroshenko Bloc lawmaker Serhiy Alekseev registered amendments to include the creation of a special anti-corruption panel. Parliament is to consider it during the fall session.

Pensions

Pension reform is also needed to unlock IMF loans. If backed, the reform bill will abolish special privileges for retirees: pensions for years of service will be assigned only for the military. The reform also stipulates that from January 1, 2018 the right for pensions for years of service for employees in education, health, social protection and other categories will be revoked.

Starting in October, the government proposes to abolish a 15 percent reduction of pensions for working pensioners. The draft law also proposes that those who work, should receive wages and pensions in full. The minimum pension will be set at Hr 1,373 or $54. The increase in pensions will affect some 9 million pensioners.

Defense

National Security and Defense Council chairman Oleksandr Turchynov claimed on Aug. 30 that a new bill on state policy of reintegration and reconstruction of the war-torn Donbas is ready to be brought in during autumn session.

The document is expected to de jure scrap the so-called anti-terror operation in the east without imposing martial law. It would proclaim Russia an aggressor, responsible for maintaining the territories it occupies, the officials say.

Nevertheless, it is also to pave the way for the peaceful reintegration of the Donbas into the rest of Ukraine. To do so, it enhances the role of the Ministry of Occupied Territories. And although the draft bill states that the Minsk agreements are the only way to end the war, it nevertheless reserves Ukraine’s right to defend itself against further Russian offensives.