Six months ago, Nelya Pogrebytska, a 26-year-old woman from a small village in Kyiv Oblast, was raped and tortured at a police station in Kaharlyk, a town of over 13,000 people located 80 kilometers south of Kyiv.

The brutal crime shocked not only the town, but the entire nation and provoked an outburst of anger over Ukraine’s failed police reform.

In the following months, a probe revealed more victims of abuse during detention at the same police station. Five police officers, including the chief, were fired and arrested. Two of them remain in custody, while others are under house arrest waiting for the trial.

In early December, the State Investigation Bureau indicted the five former police officers on charges of torture, rape and forced disappearances. And, for the first time, one of them is a police chief facing a prison term for tacitly permitting brutal practices.

In Ukraine, a country where police brutality and violence against women are widespread and often go unpunished, the fact that the Kaharlyk case will reach the court is a big step forward.

“It gives hope to other victims,” says Kateryna Mitieva, spokeswoman for Amnesty International Ukraine, adding that public and media attention contributed to progress in the case.

Systematic brutality

Nelya Pogrebytska has been publicly outspoken since accusing Kaharlylk police officers of rape on May 23, 2020. (TSN)

In the early evening of May 23, Nelya Pogrebytska entered the Kaharlyk police department. She had been summoned as a witness to the burglary of her neighbor’s shop.

She only left around 4 a. m. the next day. During the night of questioning, she was beaten, asphyxiated with a gas mask, threatened with an electric shocker and raped.

Pogrebytska later identified Mykola Kuziv, 35, the head of criminal investigations, as her torturer and Serhiy Sulyma, 29, criminal investigator, as her rapist. The two men were detained and pleaded not guilty. They now face up to 12 years in prison.

Pogrebytska lives in the village of Stavy near Kaharlyk with her six-year-old daughter, who has cerebral palsy. She declined to be interviewed for this story.

Since that night, she has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, her lawyer says. Despite being provided with security guards, she fears that Kuziv and Sulyma might be released on bail one day and come after her.

The State Investigation Bureau probe concluded that Pogrebytska was one of five victims of Kaharlyk police officers, who used torture to coerce confessions to crimes such as theft.

The victims were illegally detained, beaten, tortured with electric shockers and left handcuffed to a radiator overnight. The police officers put a gas mask over their heads, blocked the air supply until they lost consciousness and fired live ammunition over their heads.

The true number of people who suffered from police brutality in the Kaharlyk police department is likely higher.

In the past, numerous people have filed complaints about unlawful actions by Kaharlyk police officers. There was even one pre-trial investigation, according to the National Police’s response to an inquiry by lawmaker Andriy Osadchuk.

Back in January, Oleksandr Saliy filed a complaint that the police officers Sulyma, Kuziv, and Yaroslav Levandyuk had burst into his apartment at night, beaten and tortured him and his friend, Oleksandr Tkach. The two men are now victims in the Kaharlyk case.

Had it not been for Pogrebytska, their story might have never have become known or reached a court.

Levandyuk and another police officer implicated in torture, Yevhen Trokhymenko, are under house arrest and face 10 years in prison. So is former Police Chief Serhiy Panasenko. Prosecutors claim he turned a blind eye to rampant brutality.

Combating brutality

Police brutality is an endemic problem in Ukrainian law enforcement. Women are at higher risk of being abused during detention, according to a recent report by the Kharkiv Institute of Sociological Research.

The reason is impunity at the heart of the law enforcement and justice system, says Denys Kobzin, who leads the institute. Police, prosecutors, judges and attorneys view themselves as one team, so they are reluctant to prosecute or testify against each other.

In 2017, Ukraine launched the State Investigation Bureau, which was tasked with investigating top officials, judges and law enforcement officers. After finishing the pre-trial investigations, it sends cases to prosecutors.

“Everything is locked down inside the system. Prosecutors have to prosecute the police officers, who are their colleagues. If a person is beaten by the police and goes to the hospital, doctors have to report to the police, and the police pass the information to the State Investigation Bureau,” Kobzin said. “No state body considers investigating cases of police brutality and involving independent organizations or representatives of the victim.”

Ukraine’s police reform, which began in 2015, has not yielded the expected result, he said. Little has changed in the police’s procedures, performance assessments and processes for investigating police brutality. Even the police officers themselves — 58.5% of them, according to a survey by Kobzin’s institute — consider the reform a failure.

Mitieva of Amnesty International gives credit to law enforcement for their quick response in the Kaharlyk case — the prompt arrest of the suspects and the ensuing probe that uncovered widespread torture at the same police department. This, she said, indicates some progress in the reform.

The National Police say they are taking measures to fight brutality in their ranks. On July 31, Interior Minister Arsen Avakov ordered the installation of Custody Records software for monitoring the handling of detainees in all police departments across the country.

“In the nearest future, Custody Records will be installed in the police departments of Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv and Kirovohrad oblasts,” Ruslan Goryachenko, head of the police’s human rights compliance department, said.

However, the software is costly. The National Police is seeking co-financing from an international organization or the local authorities, he added.

Custody Records software has already been installed in all 133 detention centers, but only six of them have it integrated with video surveillance.

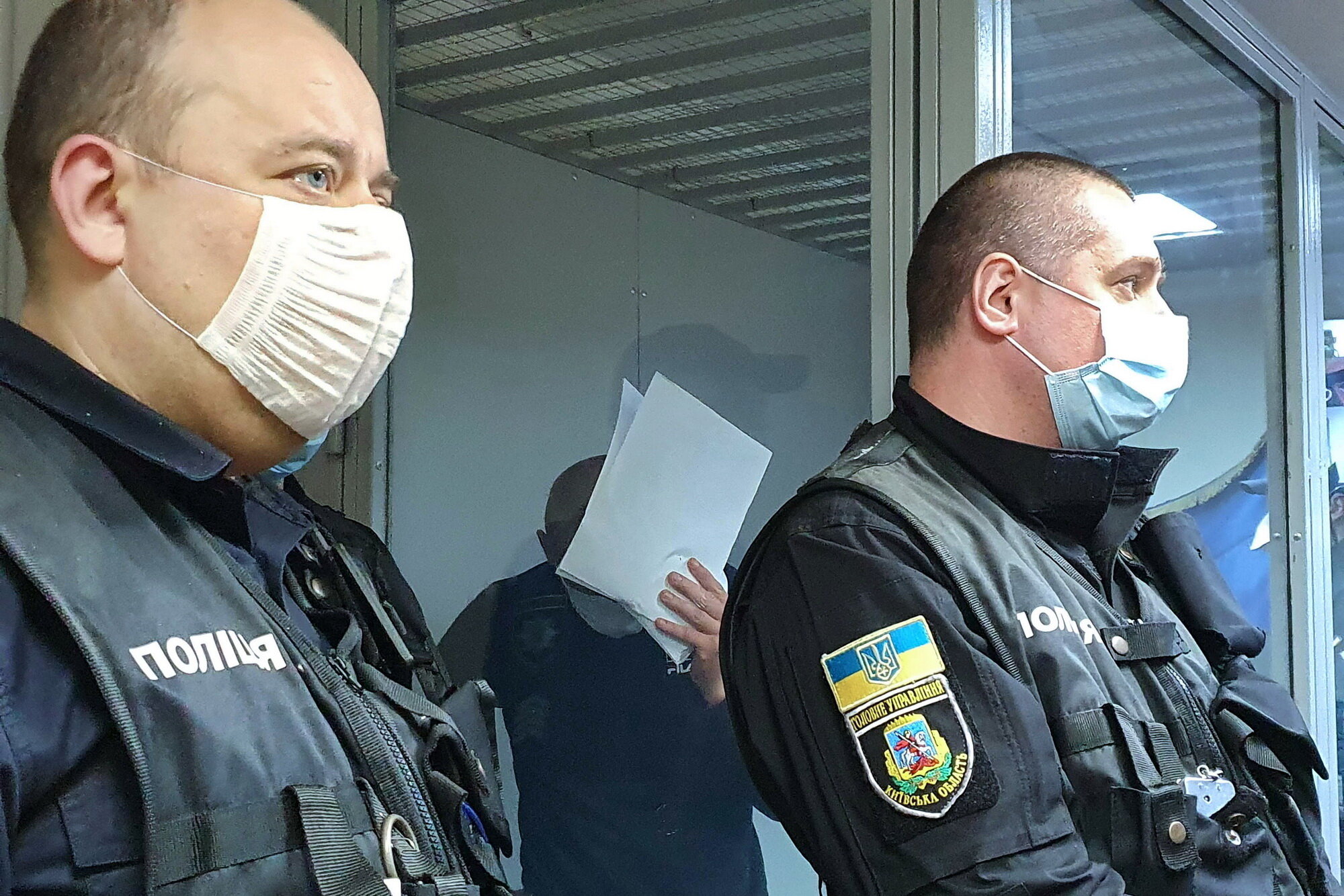

Mykola Kuziv (L) and Serhiy Sulyma (R), former police officers of Kaharlyk police department charged with torture and rape of Nelya Pogrebytska. (Anton Gerashchenko/facebook)

Against the system

Olena Sotnyk, one of four lawyers representing Pogrebytska, has some concerns about the upcoming trial. The main one at the moment is the jurisdiction.

In a provincial town like Kaharlyk, the impartiality of a local court is compromised, she says, because of relations between the police, prosecutors and judges.

There is a chance, however, that if all four judges of the Kaharlyk district court self-recuse, the case will be tried in a different court.

Another potential challenge is that other victims in the case are either former convicts or are currently under investigation for minor crimes. This makes them susceptible to pressure. Moreover, they could face prejudice from the legal system and the public.

Sotnyk, a former lawmaker, says she did not plan to go back to legal practice, but could not remain on the sidelines when she heard about Pogrebytska’s case. She teamed up with three other women: Zlata Symonenko, a white-collar defense lawyer, and Tetyana Kozachenko and Anna Kalynchuk, two private lawyers who used to lead the lustration department at the Justice Ministry.

Symonenko told the Kyiv Post back in October that, for her, taking this case was about breaking the silence surrounding violence against women.

“There is a tendency when women are told not to complain, not to speak up about violence,” she said.

Pogrebytska, unlike many victims, went public.

The all-female team of defenders hopes that the trial could change how the criminal justice system responds to rape.

Sotnyk says investigators, who are predominantly men, are untrained to handle sensitive conversations with victims of rape, especially women, who have suffered psychological trauma. And women feel ashamed to talk to men about the personal details of rape.

She also says the existing approach to investigating rape should change. Today, a victim has to prove they were raped with physical evidence, such as bruises. But sometimes victims do not resist if they are in shock or fear of more violence.

“It is his words against hers. He says the sex was consensual. She has to prove it was rape,” she said, describing rape cases in general. “The victim’s words should be trusted more. They should be the key.”