In early February, President Volodymyr Zelensky shut down three pro-Kremlin TV channels. The bold move was praised by activists, journalists, and pro-Western observers.

However, when the dust from the attack settled, Ukrainian TV remained what it was: not free.

Ukraine’s top 10 TV channels serve as political tools for a handful of oligarchs. They directly influence their channels’ agenda, giving airtime to friendly politicians, while muting and lambasting those who threaten their interests.

Moreover, the pro-Kremlin agenda didn’t disappear from the air.

Narratives and lies similar to the ones aired on the three channels that were shut down are still promoted on the news-and-views station Nash, reportedly linked to Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, as well as on Inter, a major channel owned by lawmaker Serhiy Lyovochkin and fugitive Kremlin-backed oligarch Dmytro Firtash.

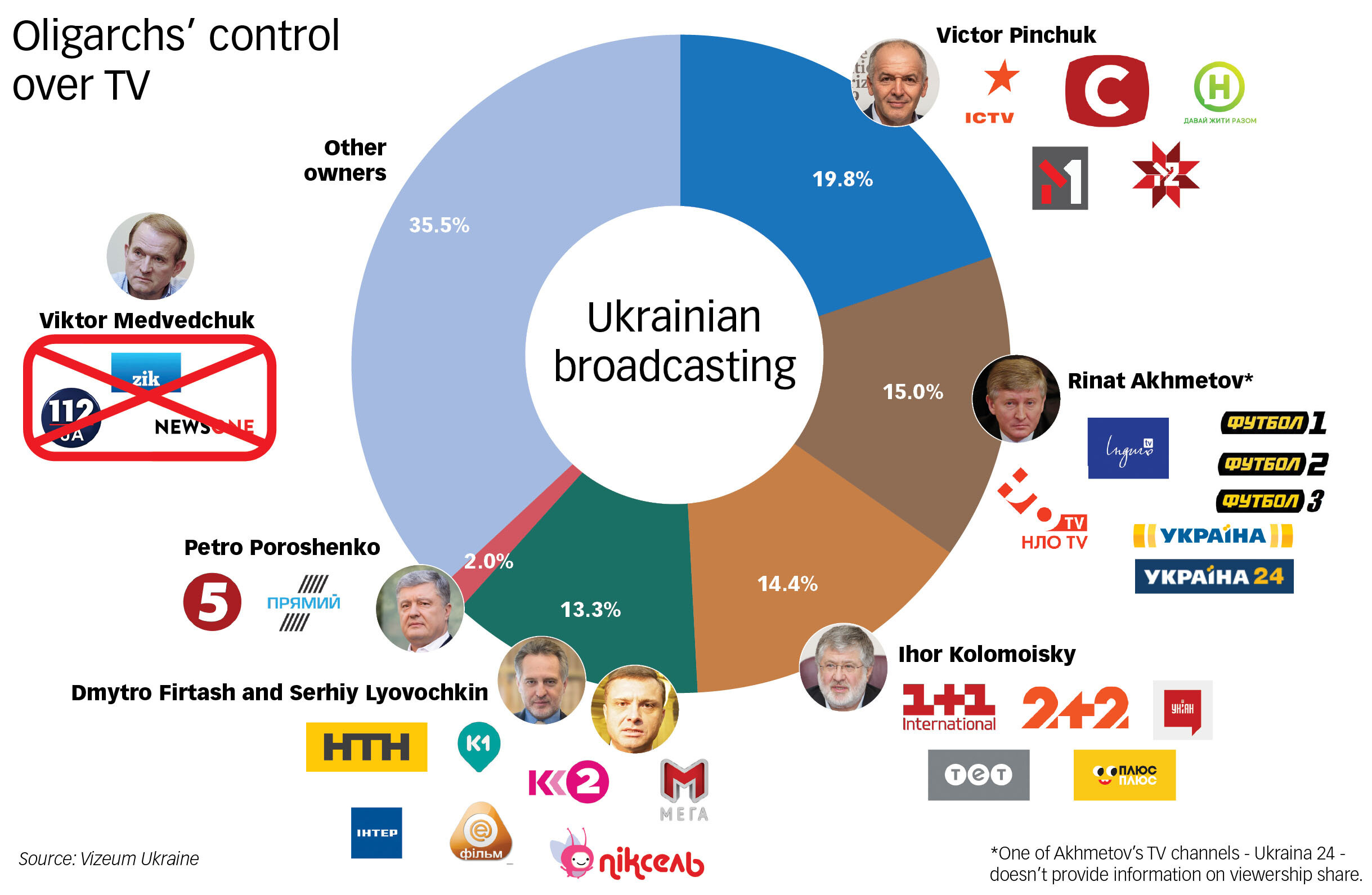

Ukrainian oligarchs Rinat Akhmetov, Victor Pinchuk, Ihor Kolomoisky, Petro Poroshenko, Dmytro Firtash and Serhiy Lyovochkin control the nation’s major television stations and media empires. Viktor Medvedchuk was in the club until Feb. 2, when President Volodymyr Zelensky ordered Medvedchuk’s three TV stations off the air as a national security risk for their Kremlin propaganda. (Kyiv Post)

Other top channels promote the agendas of oligarchs Ihor Kolomoisky, Rinat Akhmetov, Victor Pinchuk and ex-President Petro Poroshenko. Deeply unprofitable, the channels survive only on cash provided by their wealthy owners — who in turn control their coverage.

Together, five oligarchs control nearly 70% of Ukrainian television.

While he shut down three pro-Kremlin stations, Zelensky has never acted on his campaign promise to limit oligarchs’ influence on their TV channels.

Kremlin-friendly network

In the past several years, the loudest voice on Ukrainian TV was the voice of Russian propaganda.

On several channels, Kremlin-friendly TV hosts were mulling public opinion to think that Ukraine is entrenched in a civil war and promoting anti-Western conspiracies.

As a result, the pro-Kremlin Opposition Platform — For Life party that holds 44 seats in parliament gained first place in the January polls. It was the first time an openly pro-Russian party led the polls since the EuroMaidan Revolution ousted Russian-backed President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014.

The man behind the revival was Viktor Medvedchuk, a friend of Vladimir Putin and former head of Leonid Kuchma’s presidential administration.

Returning to the national stage after a decade in the shadow, Medvedchuk consolidated fractured Kremlin sympathizers and took control of three news TV channels formally owned by his associate Taras Kozak — Channel 112, NewsOne, and ZIK.

Medvedchuk is no stranger to abusing freedom of speech. It was during his tenure that Kuchma’s office started sending written instructions to the media about the coverage it wanted. Those instructions were known as “temniki.”

The three-channel group acted like one, promoting the Kremlin’s agenda.

In 2018, parliament voted to impose sanctions against pro-Kremlin media, primarily those controlled by Medvedchuk.

However, the National Security and Defense Council never acted on the parliament’s request. According to the transcript of the council’s meeting obtained by the Kyiv Post, Poroshenko personally withheld sanctions against Medvedchuk’s media from the agenda, saying that the decision needs more work.

Lawmakers with pro-Kremlin Opposition Platform – For Life Serhiy Lyovochkin (L), Viktor Medvedchuk (C) and Vadym Rabinovych speak in the parliament session hall on Feb. 16, 2020. Medvedchuk’s three TV channels – ZIK, NewsOne and Channel 112 – have been shut down by President Volodymyr Zelensky. Channels owned by Lyovochkin remain on air. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

Anatoly Oktysiuk, a political expert at local think tank Democracy House, says that Poroshenko was deliberately nurturing Medvedchuk and his pro-Kremlin allies to face a comfortable opponent during future elections.

“Poroshenko knew that Medvedchuk isn’t an actual threat to him, rather a convenient embodiment of evil,” Oktysiuk told the Kyiv Post.

As a result, during the 2019 parliament elections, Medvedchuk’s pro-Kremlin party gained second place, reviving him as a nationwide politician.

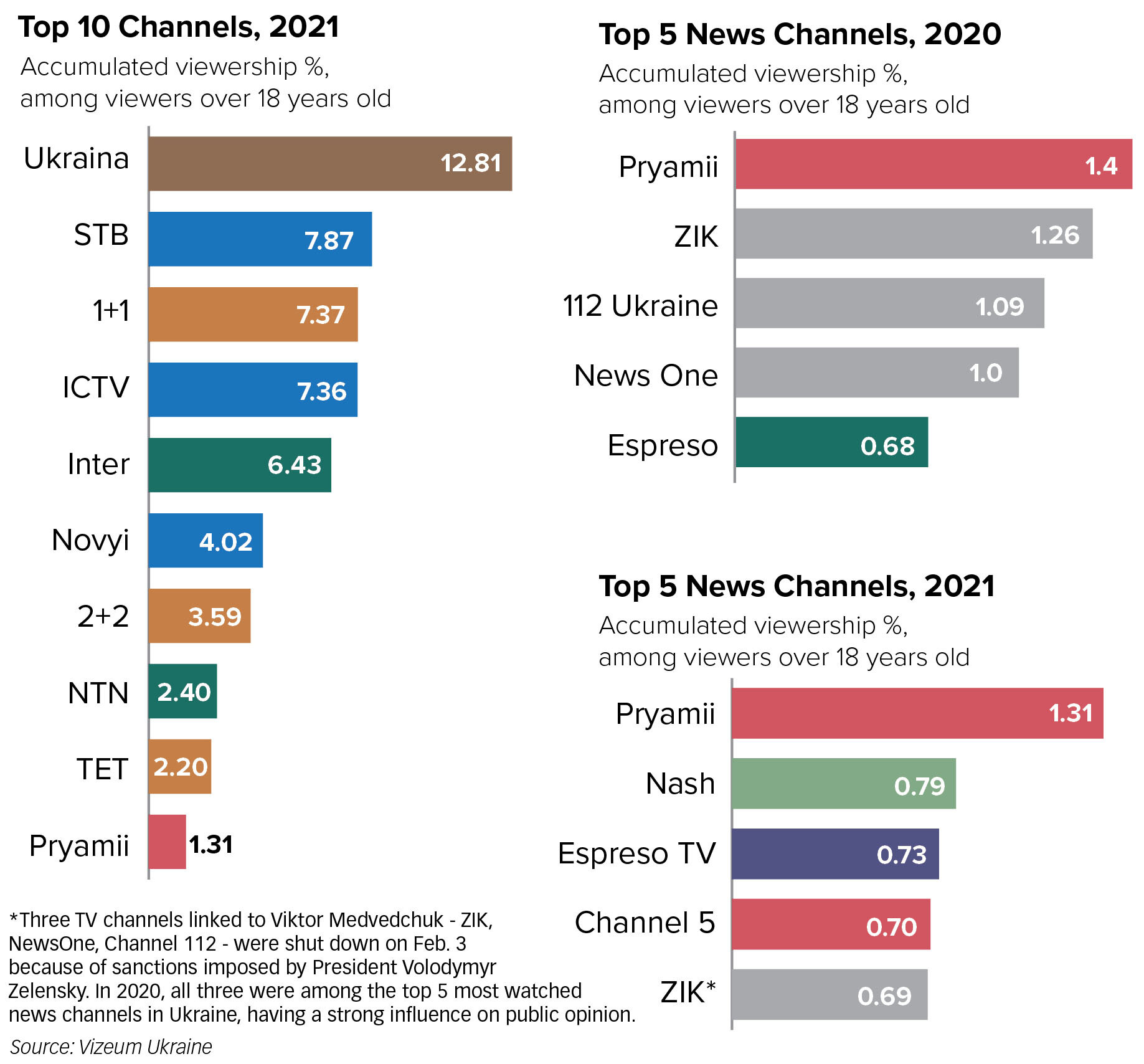

In February, when the National Security and Defense Council imposed sanctions against pro-Kremlin lawmakers and their vast businesses and media, Medvedchuk’s three TV channels were among the most-watched news channels in Ukraine with nearly 4% of the total viewership.

After the sanctions, they continued to go live on YouTube. Their one attempt to return to broadcasting — by acquiring a small TV station and rebranding it — failed. One hour after it went live on Feb. 26, the station was taken off the air.

The channels also filed several complaints about the sanctions to the Supreme Court. There has been no decision yet.

Russian sympathizers

Even without Medvedchuk’s channels, pro-Kremlin propaganda isn’t gone. TV channels Inter and Nash continue spreading anti-Western narratives.

Inter is one of Ukraine’s oldest TV channels. It is in the top 5 most-watched channels and has a bigger audience than Medvedchuk’s three channels combined.

Inter is owned by Firtash, a Ukrainian energy and chemical tycoon, who lives in exile in Vienna. Firtash has been fighting extradition to the United States since his arrest in 2014 on bribery charges that he denies.

Pro-Russian lawmaker Lyovochkin also owns a share. His ally, lawmaker Yuriy Boyko, the most popular pro-Russian politician in Ukraine, has a regular presence in news segments, talk shows, and commercials.

However, Inter has toned down its pro-Russian propaganda after Zelensky imposed sanctions against Medvedchuk’s media, according to Otar Dovzhenko, an observer at the Detector Media watchdog.

“Firtash-Lyovochkin’s group understood the hint,” said Dovzhenko.

Another channel, Nash, didn’t. Although it has a small audience, it is now the most heavily pro-Kremlin channel in Ukraine. Pro-Russian lawmaker Yevhen Muraev created Nash after a fallout with Medvedchuk.

Before Kozak-Medvedchuk’s sanctions were shut down, Nash had just 0.38% share of the TV audience in January.

After sanctions, Nash became one of the most-watched news channels in Ukraine with over 1.5% of the viewership.

The ownership and control over Ukraine’s major TV stations are highly concentrated among a handful of oligarchs who also have major interests in the leading sectors of Ukraine’s economy. This has long been a source of concern in Ukraine. The news TV stations, in particular, are used as propaganda outlets promoting their owners’ political and private interests. (Kyiv Post)

Despite a very similar agenda, Nash avoided sanctions and this didn’t pass unnoticed. One of the first to bring attention to the fact was ex-President Poroshenko.

Nash could have been placed under sanctions together with Medvedchuk’s channels in 2018, by the Security Council. But, just like Poroshenko saved Medvechuk’s channels by taking them off the agenda Avakov asked for Nash to be withdrawn at the same meeting.

According to the transcript, Avakov said that Nash was affiliated with Akhmetov. Withdrawing Medvedchuk’s channels but sanctioning Akhmetov’s would be seen as taking sides, he said at the meeting.

There is no official connection between Nash and Akhmetov or Avakov.

Poroshenko cheerleading

When running for president in 2014, Poroshenko said he would sell his Channel 5, which he owned since 2004. He not only didn’t do that, but he acquired another TV channel, Pryamii.

Together, the two stations today have just a 2% of the general viewership, but Pryamii is among the most watched news-and-views channels.

Although Pryamii was launched in 2017, Poroshenko has always denied owning it, despite obvious links and heavily pro-Poroshenko coverage.

In February, after Medvedchuk’s channels were shut down, Poroshenko said that he bought Pryamii from its official owner Volodymyr Makeenko to save it from possible sanctions. His claim didn’t make legal sense because Poroshenko’s status as a lawmaker doesn’t protect his media from sanctions.

On Pryamii, Poroshenko continues his tactic of conveniently juxtapositioning himself against a pro-Russian opponent. Two politicians that often appear on Pryamii are Poroshenko and Boyko.

Pryamii TV channel airs a speech of channel owner ex-President Petro Poroshenko on Feb. 18, 2021.

Top speakers on Pryamii are usually lawmakers from Poroshenko’s European Solidarity party, while news segments begin by talking about Poroshenko’s charitable work or statements he published on Facebook or Twitter.

Coverage on Channel 5 is similar. On Valentine’s Day, it aired a flattering interview with Poroshenko and his wife.

Both channels relentlessly criticize Zelensky and his government.

Akhmetov & Kolomoisky

Akhmetov’s Ukraina and Kolomoisky’s 1+1 are the most popular TV channels in Ukraine with 12.8% and 7.4% of viewership as of March.

Both channels have diverse programming — from Ukrainian soap operas and American movies to news segments and political talk shows. During news segments and talk shows, each channel promotes the owner’s agenda and gives airtime to politicians favored by the owner.

Dovzhenko said that owners use their TV channels in several ways. On one hand, they can whitewash their name and promote their business in the eyes of the government, politicians, and competitors. On the other, the channels are used to influence public opinion and sell that service to politicians.

“This part of the channel’s activity is usually important before elections when certain political parties need to be promoted,” said Dovzhenko.

The most recent example could be seen during the October local elections.

Akhmetov’s Ukraina TV channel was actively promoting Opposition Bloc, a less popular pro-Russian party tied to Akhmetov. The main speakers were party leader lawmaker Vadym Novinsky and politician Borys Kolesnikov. Both are Akhmetov’s business partners. It didn’t help — the party performed poorly in the elections.

Akhmetov’s media also promoted two populist oligarch-friendly politicians: Oleh Lyashko, leader of the Radical Party, and Yulia Tymoshenko, leader of the 24-member Batkivshchyna faction in parliament.

In 2020, Akhmetov launched news-and-views channel Ukraina 24. It’s not clear how much it grew his influence on the audience: the new channel doesn’t reveal viewership data.

On both Ukraina and Ukraina 24, neutral news segments blend in with those that promote Akhmetovfriendly politicians or the oligarch’s charity work. Ukraina 24’s hosts, recruited from pro-Kremlin channels, interview Lyashko about how importing cheap electricity is bad for Ukraine. Akhmetov’s DTEK is the largest electricity producer in Ukraine and lobbies against electricity imports.

It is similar to channels owned by the other heavyweight oligarch, Kolomoisky.

His channels backed Zelensky and his party during the 2019 elections but since then the relationship went sour.

Zelensky supported the anti-Kolomoisky bank law and, most recently, excluded Kolomoisky’s associate Oleksandr Dubinsky from his Servant of the People parliament faction.

As a result, Kolomoisky’s channel has focused on promoting the oligarch’s new project — For the Future, a party led by lawmaker Ihor Palytsa, Kolomoisky’s long-standing business partner. The party members hold 24 seats in parliament. With Kolomoisky’s media support, it scored fifth place in the 2020 local elections.

Right now, Kolomoisky’s 1+1 promotes For the Future candidate Oleksandr Shevchenko in upcoming by-elections in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Shevchenko ran the Bukovel ski resort when Kolomoisky owned it.

After the Kolomoisky-Zelensky relationship cooled, members of Zelensky’s administration and party have migrated from Kolomoisky’s 1+1 channel to Akhmetov’s Ukraina 24. Speaker Dmytro Razumkov, Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal and Chief of Staff Andriy Yermak have all given lengthy interviews on Ukraina 24 in the past several months.

Lower-profile Pinchuk

The less political, yet influential oligarch Viсtor Pinchuk has the largest share of Ukrainian TV. His three channels — ICTV, STB and Novyi Kanal — have 18% of Ukraine’s TV viewership.

Pinchuk, the son-in-law of Kuchma, who ruled from 1994–2005, is notorious for remaining on good footing with Ukrainian political elites.

His stance on Russia’s war against Ukraine has come under criticism. While Pinchuk acknowledges that Russia invaded Ukraine and occupied Crimea, he advocated for letting Crimea go in return for peace in eastern Ukraine.

His metallurgical company Interpipe sells its produce to Russia. His channels tend to follow a similar line.

“For the last 15 years, Pinchuk’s channels have been loyal to any government if it doesn’t attack Pinchuk and does not touch his father-in-law Kuchma,” Dovzhenko told the Kyiv Post.

A notable exception is Medvedchuk’s Opposition Platform which is unofficially banned from Pinchuk’s TV.

Overall, Dovzhenko says “there is no ‘magic pill’ that would de-oligarchize the media.”

“The oligarchic media will not stop praising their owners and their business, but at least there is a chance that they will stop throwing information ‘dirty bombs’ at the society,” he adds.