Sergei Korotkikh, a member of Ukraine’s Azov volunteer force, has been a member of neo-Nazi and far-right movements in three countries.

Korotkikh, also known by his nicknames Malyuta and Botsman, grew up in Belarus, then moved to Russia in the early 2000s and went on to Ukraine in 2014. In Ukraine, he fought against Russia as part of the Azov contingent and was a top police official under ex-Interior Minister Arsen Avakov.

Some of the groups that Korotkikh joined have publicly praised Nazi Germany and Adolf Hitler and declared a “racial war” on immigrants. In Ukraine, Korotkikh continues to espouse far-right ideas and casts himself as a crusader against Western liberalism.

But questions are raised about whether Korotkikh’s actions are more dangerous than his views.

Members of the far-right groups co-led by Korotkikh have been convicted of murders and were involved in numerous assaults.

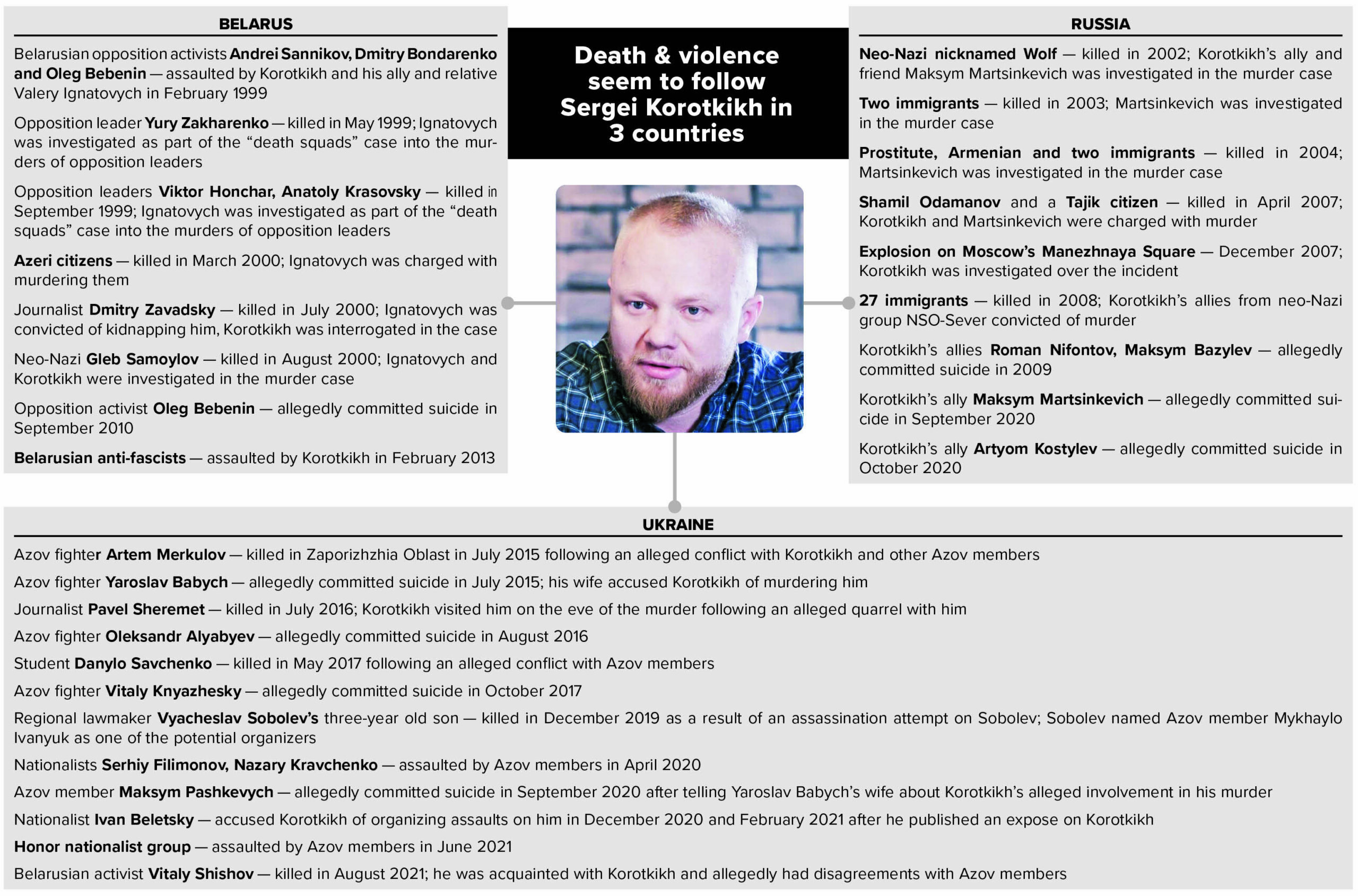

Also, multiple people around Korotkikh have been killed or died in suspicious circumstances in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. Some of the dead may have known a great deal about the fighter and his alleged crimes.

Korotkikh could be crucial in helping to solve the 2016 murder of Belarusian journalist Pavel Sheremet and the 2021 hanging death of Belarusian activist Vitaly Shishov. The official Sheremet investigation has effectively reached a dead end, and no progress has been reported in the Shishov case.

Korotkikh, who was charged by Russia with the 2007 murders of two immigrants near Moscow, had been investigated in several criminal cases before but always escaped punishment. His critics say that he got away with everything due to his alleged links to Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian intelligence agencies and law enforcement bodies, and due to testimony he gave against his closest associates.

In Ukraine, he and his fellow Azov fighters enjoyed the patronage of Avakov, the former interior minister and one of the nation’s most powerful officials from 2014–2021.

Ukraine’s dysfunctional law enforcement has failed to investigate Korotkikh’s alleged wrongdoings, deepening the sense of impunity with which extremists operate in Ukraine. Despite ultra-nationalists being a political fringe group in Ukraine, rumors about Korotkikh have played into the false Kremlin narrative that neo-Nazis are running the country.

Korotkikh, who previously denied the accusations of wrongdoing, did not respond to requests for comment.

“Azov’s official position can only be stated about the events that concern Azov fighters during the period when they officially served,” the press service of the Azov regiment told the Kyiv Post. “The questions you asked do not concern (Azov’s) activities.”

Yulia Kuzmenko (L), Yana Dugar and Adnriy Antonenko (R), who were charged with the 2016 murder of journalist Pavel Sheremet, sit in a courtroom on Jan. 12, 2020 in Kyiv. Evidence against them is weak, and Azov member Segrei Korotkikh’s critics suspect him of involvement in the murder. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Belarusian period

Korotkikh, who is of Belarusian descent, was born in Russia and grew up in Belarus, where his first intelligence links appeared.

In the 1990s, Korotkikh served in Belarus’ military intelligence and studied at the Belarusian KGB academy.

At the time, both Korotkikh and his relative Valery Ignatovych were among the leading members of the Belarusian branch of RNE, a Russian neo-Nazi group.

The first violent episodes, murders and mysterious deaths around Korotkikh also occurred in Belarus.

In February 1999, Korotkikh took part in an assault by neo-Nazis against Belarusian opposition activists Andrei Sannikov, Dmitry Bondarenko and Oleg Bebenin.

“Sannikov was lying in a pool of blood, and several people were kicking him,” Bondarenko told the Charter 97 news site in 2013. “He was in effect being killed.”

Korotkikh later dismissed the incident as an “ordinary clash between subcultures.”

In 2010, Bebenin was found dead in what appeared to be a fabricated suicide.

Korotkikh’s relative Ignatovych has been given a life sentence by a Belarusian court for a murder and an armed assault that took place in Minsk Oblast in December 1999. Ignatovych was also charged with killing five Azeri citizens in March 2000.

Despite extensive incriminating evidence, Ignatovych was acquitted of this crime. Korotkikh testified against Ignatovych, saying that the knife found on the crime scene belonged to his relative.

Ignatovych has also been convicted of kidnapping Belarusian journalist Dmitry Zavadsky, who disappeared in July 2000 and is believed to be dead. He was the cameraman and friend of Sheremet, who was assassinated in Kyiv in 2016.

A spade with Zavadsky’s DNA was found in Ignatovych’s car but that was not enough to upgrade the conviction from kidnapping to murder.

Korotkikh was also interrogated in the Zavadsky case but escaped official charges. He told a Belarusian news site in 2015 he had an alibi in the case.

In 2000, two bodies were found near the town of Krupky in Minsk Oblast. Zavadsky’s mother Olga and lawyer Garry Pogonyaylo said one of them could belong to Zavadsky. Both Korotkikh’s and Ignatovych’s parents grew up in Krupky.

At around the same time, Korotkikh and Ignatovych had a conflict with Gleb Samoylov, head of their RNE branch in Belarus, and Samoylov expelled Ignatovych from the organization. Samoylov was murdered on Aug. 5, 2000 — after Ignatovych had already been arrested.

Former Belarusian investigator Dmitry Petrushkevych told the Kyiv Post that Korotkikh had also been investigated in the case of Samoylov’s murder. But, again, he was not charged.

Ignatovych’s murky career did not prevent Korotkikh from praising him.

“Valery (Ignatovych) has been accused of a lot, but nobody mentions that he was a man of high quality,” he told Ukrainian journalist Natalia Vlashchenko in 2019. “I believe him to be one of the most consistent and ideologically-driven people I’ve known.”

Korotkikh’s Russian friend Maksym Martsinkevich later described a 2005 trip to Minsk with Korotkikh in his audio book Destrukt and said that both of them supported the Belarusian regime as the epitome of their neo-Nazi ideals.

“Malyuta (Korotkikh) told me that they here they beat Jews, here they beat Asians, and here they kicked the shit out of an (opposition) activist,” Martsinkevich said in a reference to Korotkikh’s description of his Belarusian period in the 1990s.

Martsinkevich said that they chased several people who looked like opposition activists around Minsk during the 2005 trip and let them go after they claimed not to belong to the opposition.

In 2013 Korotkikh and Marsinkevich also clashed with Belarusian anti-fascists, and Korotkikh stabbed one of them with a knife.

Activists hold portraits of murdered Belarusian activist Vitaliy Shishov at a rally next to the Belarusian Embassy in downtown Kyiv on Aug. 3. Shishov was acquainted with Azov member Sergiy Korotkikh and allegedly had disagreements with Azov before he was found hanged in a Kyiv park. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Murder of immigrants

In the early 2000s Korotkikh moved to Russia, where he became one of the leaders of the National Socialist Society, founded in 2004. It openly supported Hitler and Nazi Germany and prepared for a “racial war.”

He was a close ally and friend of Martsinkevich, the leader of the neo-Nazi group Format 18.

In Russia, Korotkikh was also accused of involvement in murders.

In April 2007, near Moscow, neo-Nazis killed Shamil Odamanov, a native of Russia’s North Caucasus republic Dagestan, and an unknown Tajik citizen. According to a 2015 investigation by Israeli documentary maker Vlady Antonevicz, the 2007 murder could have been carried out by Korotkikh and his allies Martsinkevich and Dmitry Rumyantsev. Korotkikh and Rumyantsev denied the accusations.

In August 2007, anonymous neo-Nazis, who said they were the National Socialist Society’s military wing published a video in which they cut off Odamanov’s head and shot the Tajik. They also declared war on immigrants and called for releasing Martsinkevich, who had been arrested in a separate hate crime case, and appointing Rumyantsev as the president of Russia.

A year before the murder – in 2006 – Martsinkevich and Korotkikh also filmed a staged video in which they wore KKK uniforms and pretended to kill a Tajik drug dealer.

At that time, Korotkikh, Martsinkevich and Rumyantsev were not charged.

But in September 2020, Martsinkevich was found dead in a Russian prison, right after he allegedly testified about Korotkikh. The Russian authorities claimed his death was a suicide.

Russia’s Investigative Committee said that before his death Martsinkevich had admitted to multiple murders, including the 2007 murder of Odamanov and the Tajik citizen. In August 2021, the Investigative Committee also charged Korotkikh with murder. He denied the accusations, dismissing them as “fake news.”

Antonevicz and Russia’s Baza investigative journalism project have published what they say is a note written by Martsinkevich to a friend.

In the alleged note, Martsinkevich confessed that both he and Korotkikh had taken part in the 2007 murder. “I told them that Malyuta (Korotkikh) cut off (Odamanov’s) head,” the note reads.

In his book “Destrukt,” Martsinkevich described numerous situations when he brutally beat up, crippled and robbed immigrants on a weekly basis. In 2007 he also publicly said that he sought to kill Tajiks and “blacks” who come to Russia.

“I have a dream to kill about 10 people, film it and go away from Russia – maybe to Mexico – and then post it from there online,” Martsinkevich said in one interview.

“He was my friend, brother and in some respects a sort of a son,” Korotkikh said about Martsinkevich after his death in 2020. “And the worldview that he had was largely formed by me… He was smart and bright, and that’s why he was killed.”

Other deaths

Martsinkevich’s alleged suicide was just one in a series of mysterious deaths. Other people who knew about Korotkikh’s alleged wrongdoings also vanished.

Martsinkevich’s alleged accomplices Roman Nifontov and Maksym Bazylev committed suicide in 2009, while another accomplice, Artyom Kostylev, took his life in October 2020, according to the official version.

Three other alleged accomplices of Martsinkevich and Korotkikh – Andrei Dedov, Oleksandr Shitov and Artyom Krasnolutsky – fled to Ukraine, according to Baza and Antonevicz.

In 2007–2008, the National Socialist Society collapsed. However, 13 members of one of its offshoots, the National Socialist Society-North (NSO-Sever) were convicted in 2011 for 27 murders and 50 assaults that took place in 2008. NSO Sever was led by Bazylev, a close ally of Korotkikh and Martsinkevich.

Just like in Belarus, Korotkikh’s career in Russia involved alleged links to Russian law enforcement. The National Socialist Society was co-founded by Maksim Gritsai, whose brother is an officer of Russia’s FSB intelligence agency.

Another link between Korotkikh and Russian authorities is through Dmitry Rumyantsev, leader of the National Socialist Society. His brother Oleg Rumyantsev is a member of advisory bodies at Russia’s Presidential Administration and other state bodies and an aide to a lawmaker from Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party.

According to video footage and a document leaked in August, Korotkikh allegedly agreed to cooperate with Russian law enforcement and gave testimony on Martsinkevich and other allies.

Olga Zavadskaya, mother of missing Dmitry Zavadsky, journalist Pavel Sheremet’s cameraman and friend, holds his portrait durind a protest in Minsk, 07 July 2005. Zavadsky disappeared on his way to pick up Sheremet from Minsk Airport on July 7, 2000. (AFP)

Ukrainian period

Korotkikh moved to Ukraine after Russia launched its aggression in 2014, joining the far-right Azov volunteer unit.

In Ukraine, he enjoyed the patronage of Avakov, Ukraine’s long-serving interior minister. Azov reported to his ministry and Korotkikh used to work as a top police official under Avakov and calls himself a friend of his son Oleksandr.

A trail of blood followed Korotkikh’s career in Ukraine too.

Artem Merkulov, a former Azov fighter, was killed in a night club in Berdyansk, a city in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, in July 2015.

Merkulov’s death followed a conflict between him and other Azov fighters, including Korotkikh, over their allegedly illegal activities, including the hijacking of cars, in Berdyansk, according to Artem Furmanyuk, a journalist who has worked for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Ostrov and other publications. Azov fighters Oleksandr Pastukh and Serhiy Znachko were also suspected of being accomplices in the murder, according to sources cited by Furmanyuk.

Another gruesome death — that of Azov fighter Yaroslav Babych — occurred in July 2015. The coroner and Azov members claimed that he died because of erotic asphyxiation.

But others argue that his death was an assassination disguised as a suicide.

Oleh Odnorozhenko, an ex-deputy head of Azov, and Babych’s wife Larysa have accused Korotkikh of killing Yaroslav — an accusation that he denied.

“My husband was vehemently against Botsman (Korotkikh). He knew his history,” Larysa Babych told the Kyiv Post.

She said that Korotkikh had personally threatened Babych in the Azov base in the village of Urzuf in Donetsk Oblast in June 2015.

“Botsman said ‘we’ve gotta do something about traitors’,” Larysa Babych recounted, describing a meeting between her husband, Azov leader Andriy Biletsky and Korotkikh in Urzuf. “And a month later my husband was dead.”

She said that she and her husband had to flee from Urzuf after the threats, and Babych had said “I would not like Korotkikh to stab me in the back with a knife.”

Sheremet

Another acquaintance of Korotkikh, Belarusian-born journalist Sheremet, was blown up in his car in central Kyiv on July 20, 2016.

Late on July 19, 2016, six Azov members, including Korotkikh and Biletsky, met with Sheremet near his house. The Azov members later said that they were going to participate in a coal miners’ rally the next day and had sought Sheremet’s advice about media strategy for the event.

Odnorozhenko and another source told the Kyiv Post that Sheremet and Korotkikh had a quarrel at the Atek factory building on the eve of the murder. The second source spoke on condition of anonymity due to fear of reprisals.

The sources said that, during the quarrel, Korotkikh and Sheremet discussed the Odesa Portside Plant and Korotkikh’s Belarusian past. In a July 17, 2016 column, three days before his murder, Sheremet criticized the release from custody of two suspects in a corruption case involving the Odesa Portside Plant.

Korotkikh’s friend and relative Ignatovych has been convicted of kidnapping Sheremet’s cameraman and friend Zavadsky, who disappeared in 2000 and is believed to be dead.

In January EUobserver, a Brussels-based English-language publication, and the Belarusian People’s Tribunal, an opposition group, published an audio recording in which alleged officials of Belarus’ KGB discussed murdering Sheremet in 2012. This leak prompted speculation on Korotkikh’s alleged role since he studied at the Belarusian KGB Academy in the 1990s.

A law enforcement source who was involved in the Sheremet investigation told the Kyiv Post that the Korotkikh version was one of the most plausible ones but it had not been properly investigated due to the political connections of Azov members to ex-Interior Minister Arsen Avakov.

There is another link to Azov in the Sheremet investigation. A source familiar with the investigation told the Kyiv Post that Zoryana Kohut, a member of the National Corps — Azov’s civilian branch, had also been investigated in the Sheremet case.

Kohut’s phone was geolocated near the place where a person filmed by surveillance cameras was taking photos of the cameras. Kohut’s face is similar to the face of the person taking pictures in the surveillance videos. She declined to comment.

Her husband, Azov member Denys Kohut, has been under investigation in the Sheremet case too.

Yet another Azov member, Ivan Yatsenko, has also been investigated in the Sheremet case, according to investigation materials obtained by the Kyiv Post.

Other deaths

One Azov fighter, Russian-born Oleksandr Alyabyev (Ervin Korf), was found dead with an assault rifle bullet in his chest at a military base in August 2016. This appeared to be yet another murder camouflaged as a suicide.

Meanwhile, the murder of student Danylo Savchenko took place in May 2017. According to sources cited by Mariupol-based news site 0629 and Furmanyuk, Azov fighters organized a raid against drug trafficking and beat up Mykola Ligotsky, who tipped them off about Savchenko, an alleged drug dealer. The Azov members are suspected of interrogating, torturing and killing Savchenko, the sources said.

Another Azov fighter, Vitaly Knyazhesky, was found dead in October 2017. According to the official version, Knyazhesky committed suicide by shooting himself with a rifle. Skeptics don’t believe in the suicide version.

Knyazhesky had previously testified against Biletsky in a criminal case.

Israeli documentary maker Antonevicz claimed in May that Knyazhesky and Yekaterina Logunova, an associate of Korotkikh and Martsinkevich based in Ukraine, resemble the couple in surveillance footage that planted the bomb under Sheremet’s car. Logunova did not respond to a request for comment.

Knyazhesky was not the last Azov member to die mysteriously.

Maksym Pashkevych, a driver for Biletsky, was found dead in September 2020. According to the official version, he also committed suicide.

Larysa Babych says that Pashkevych died after he told her about Azov members’ alleged participation in her husband Yaroslav’s death.

According to Larysa Babych, Pashkevych had claimed that he had driven Azov members to Babych’s house, and that six Azov members, including Korotkikh, killed Yaroslav. He also told her that he was afraid of being killed for leaking information about her husband’s death.

Meanwhile, Ivan Beletsky, a Russian-born anti-Kremlin nationalist who lives in Ukraine, has accused Korotkikh of organizing two attacks against him in December 2020 and February 2021 as revenge for Beletsky’s criticism of Korotkikh. He denied the accusations.

Beletsky said that they told him to kneel and apologize before Korotkikh and threatened to kill him. He said that he recognized one of the assailants as Artyom Krasnolutsky, an associate of Korotkikh from Russia.

“I was strangled until I was unconscious,” Beletsky said about the February incident. “They stretched my arms and beat me in the celiac plexus… They told me they would kill me.”

Shishov

Korotkikh has also admitted to being acquainted with Vitaly Shishov, head of the Belarusian House — a Belarusian opposition group in Kyiv — and having links to the organization.

On Aug. 3, 2021, Shishov was found hanged in a park on the outskirts of Kyiv in what appears to be a murder disguised as a suicide. Many blamed Shishov’s death on the Belarusian KGB, prompting yet another wave of speculation on Korokikh’s alleged role due to his studies at the Belarusian KGB Academy.

Korotkikh told the TV channel Nash and the Zaborona news site that he had helped Shishov get a residence permit and registered him in his own apartment.

A source in Kyiv’s Belarusian diaspora told the Kyiv Post that there was a split in Kyiv’s Belarusian community due to Korotkikh’s attempt to take over the protest movement against Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko in late 2020. Many people were fearful of Korotkikh and did not trust him, the source said.

Shishov was not comfortable with the idea of Azov ultra-nationalists dominating the Belarusian House, the source said. He tried to distance himself from Korotkikh and even to remove him from the movement, according to the source.

Rodion Batulin, a deputy head of the Belarusian house, is a close associate of Korotkikh. He declined to comment.

Batulin’s far-right background is also controversial. His Telegram account is called @denverevki — a Russian translation of “Day of the Rope” — a term from a book by U.S. neo-Nazi writer William Luther Pierce, referring to the lynching of racial and ethnic minorities.

Batulin left Ukraine before Shishov’s death, prompting suspicion that he was trying to create an alibi. On Aug. 4, the Security Service of Ukraine banned Batulin from entering the country, citing national security concerns.

The Belarusian House said Shishov had noticed that he had been under surveillance.

According to WhatsApp correspondence published by the Belarusian House in August, in June Batulin asked Shishov to tell the police he was being watched.

“Make sure that, when you are killed, people won’t say that Botsman (Korotkikh) sent me,” Batulin advised him. “So that everyone understands that it’s the (Belarusian) KGB.”