Nearly a year after the first face-to-face meeting between the presidents of Ukraine and Russia in Paris, talks over bringing peace to the Donbas have stalled again as a fragile ceasefire holds in the war-torn region.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted the priorities of the countries involved in the Donbas peace process from implementing the agreements reached in Paris. Meanwhile, restrictions meant to combat the spread of the virus have worsened the humanitarian crisis in the Russia-occupied region.

Now talks to end Russia’s war have resumed, but another problem has arisen.

A member of Ukraine’s delegation to Minsk accused the mediator, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), of acting in favor of Russia, the aggressor in an expansionist war that has dragged on for nearly six years and killed over 14,000 people.

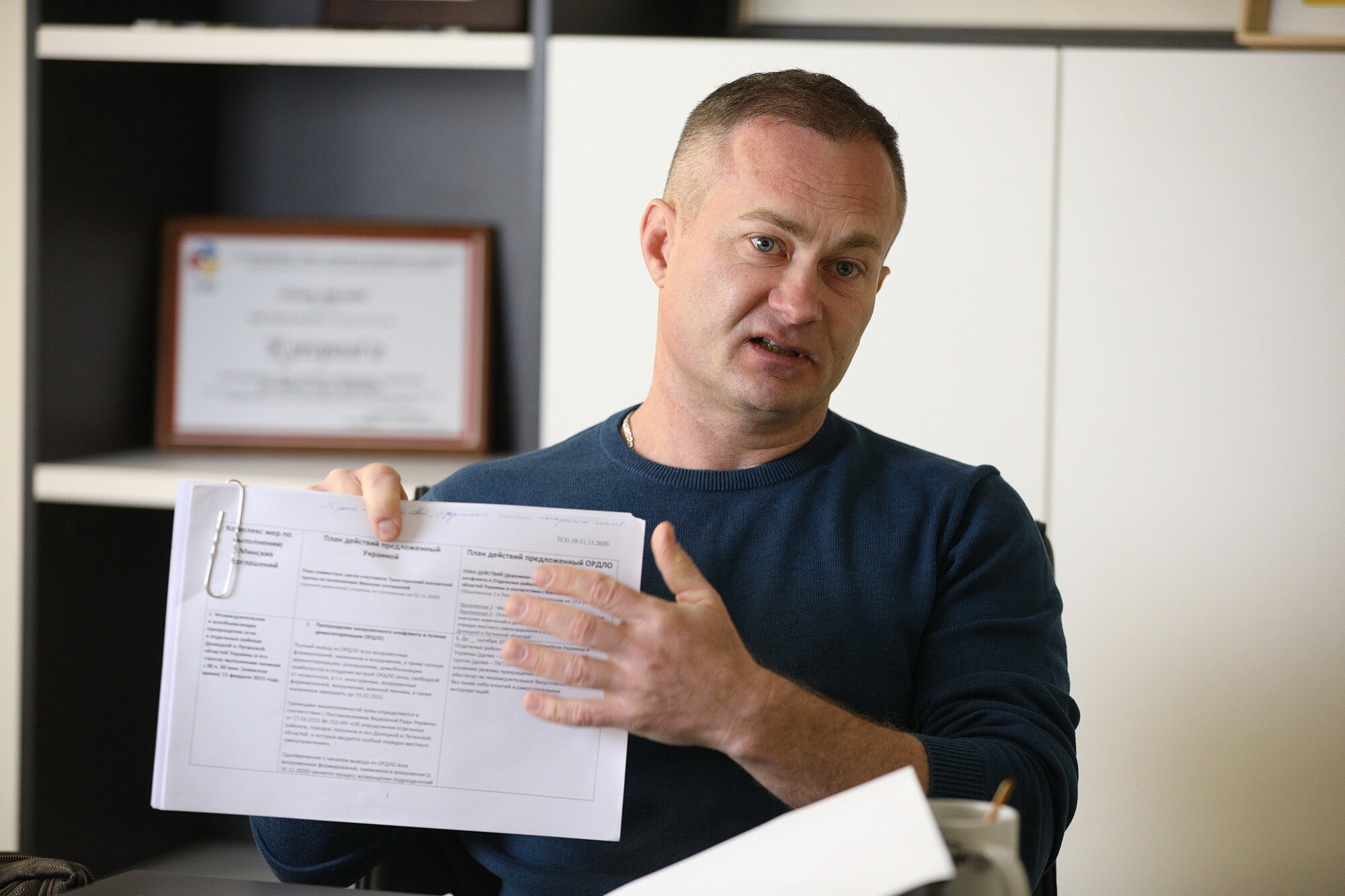

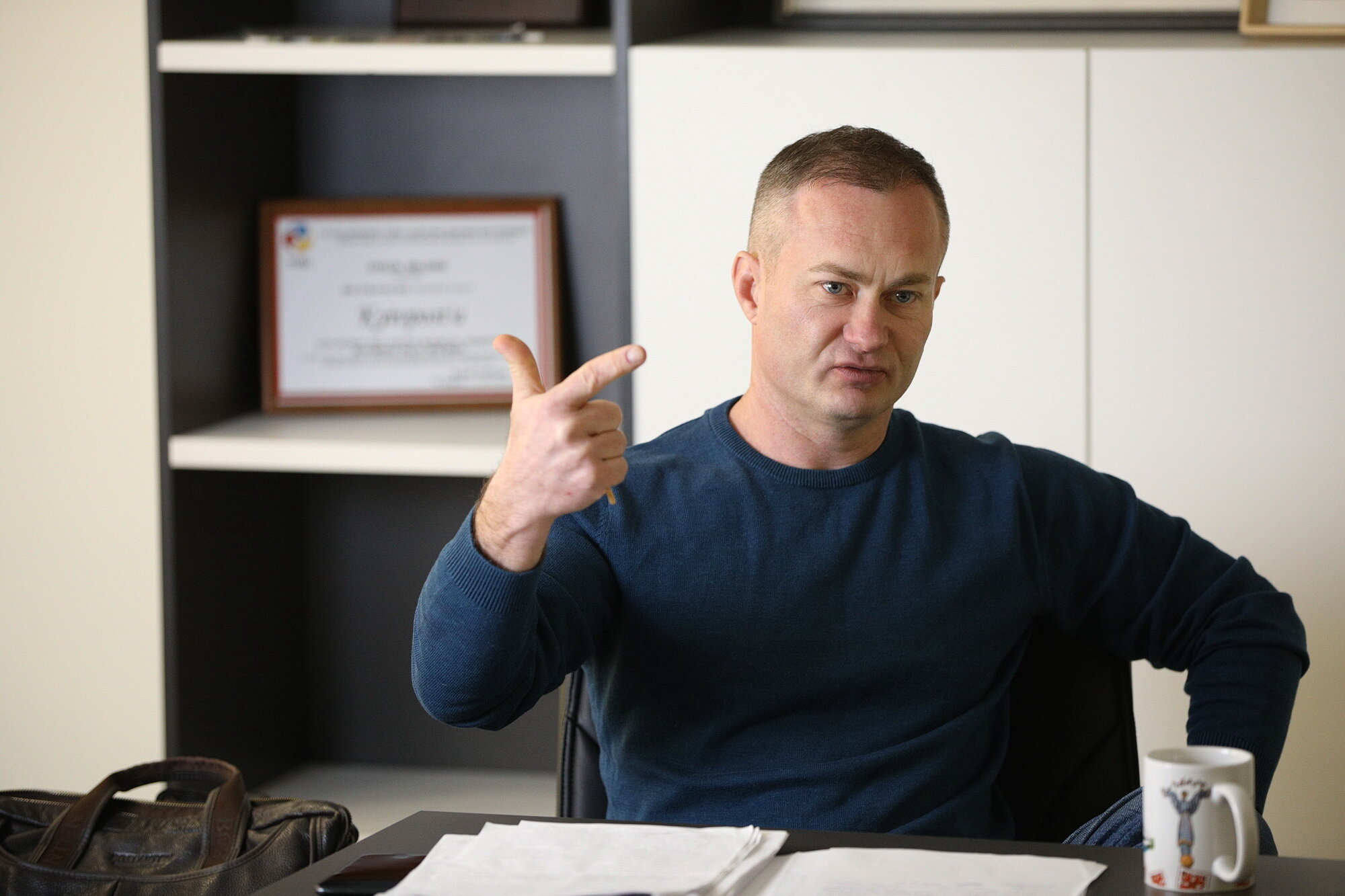

In an interview on Nov. 18, Serhiy Garmash told the Kyiv Post that the OSCE had started treating the Kremlin-backed authorities of Donetsk and Luhansk as an independent party in internal documents, despite the fact that the Trilateral Contact Group officially consists only of three parties: Russia, Ukraine and the OSCE.

This helps Russia advance its narrative that it has nothing to do with militants in the Donbas — whom it presents as separatists. In fact, the Kremlin finances and controls them, according to Garmash, a Donbas-born journalist and delegation member.

“The OSCE’s behavior hinders the conflict resolution and breaches the Minsk Protocols,” he said.

OSCE refused to comment on these allegations.

Fourth party in Minsk?

Russia-backed delegates from the Donbas, who claim to represent two unrecognized republics in the region, have been present in the Minsk peace talks since the beginning of 2014. They even signed the Minsk agreements, albeit not as a negotiating party. Rather, they were part of the Russian delegation.

In June, Kyiv appointed four new members to its delegation to Minsk. They are native residents of the Donbas who left for Ukraine-controlled territory after Russia invaded in 2014.

Garmash was one of them.

Now, representatives of the Donbas participate in both the Ukrainian and Russian delegations.

However, Garmash said, the so-called separatists still enjoy a more privileged status, and the OSCE has started treating them as an independent fourth party.

To support his claims, he showed the Kyiv Post a copy of an internal document compiled by Pierre Morel, a French diplomat and OSCE coordinator of the Minsk peace process’ political subgroup.

The document, which Morel presented during the group’s meeting on Nov. 11, is a chart comparing two new peace plans: the one Ukraine’s delegation prepared and the one suggested by representatives of the occupied Donbas – Russia’s proxies.

As the breakaway region is not a negotiating party, its representatives do not have the power to independently submit any documents in the Minsk negotiations, Garmash said.

“There can only be two plans, Ukraine’s and Russia’s. What they suggested and what the OSCE consequently presented to us for discussion, that so-called peace plan by representatives of (occupied) Donetsk and Luhansk, is illegitimate,” Garmash said.

Garmash believes Morel’s document legitimizes the breakaway Donbas and violates the Minsk Protocols.

“Maybe the OSCE is not viewing them as a party to the peace talks, but it allows them to behave like one. The OSCE created all the conditions for them,” he said.

About a month ago, Garmash and his colleagues sent a letter of complaint to Morel, but never heard back.

“They’re not just ignoring me. They’re ignoring 1.5 million internally displaced people from the occupied Donbas whom I represent,” Garmash said. “This is what Russia wants, and the OSCE as a moderator is taking Russia’s side in this case.”

He is not the only one who feels the OSCE is biased.

“This allows Russia to impose its narrative about a civil war (in Ukraine),” said Sergiy Solodkyy, first deputy director of the New Europe Center think tank in Kyiv.

The problem is that, while several agreements set the commitments of each side in the peace process, in reality, the Trilateral Contact Group has virtually no hard and fast rules defining exactly how it should operate, according to Solodkyy, an expert in foreign policy and security.

“The absence of clear rules leads to a situation where Russia can do whatever it wants,” he added. “These look like negotiations of goodwill — if there was a will and it was good. But there isn’t.”

The OSCE does not have much power to rein in Russia, according to Solodkyy.

Ukraine’s delegation, in turn, is not doing enough to stop OSCE behavior, Garmash said.

The Ukrainian delegation’s spokesman, Oleksiy Arestovych, did not reply to a request for comment.

Russia is happy

Russia feels relatively comfortable with the OSCE serving as a mediator in Minsk, political analysts believe.

It is more uncomfortable for Moscow to meet in the Normandy Format, the highest level of peace negotiations on the Donbas, where the presidents of Ukraine and Russia meet and the leaders of Germany and France serve as mediators.

“If the Ukraine issue is discussed on the international level, this brings the attention of the world’s media and experts in regional politics to Russia’s responsibility (for the war),” Solodkyy said.

“It’s obvious why Russia tries as hard as possible to avoid such an international format,” he added.

Both Berlin and Paris are trying to make a reluctant Moscow stick to peacemaking. Russia, however, has a long track record of attempting to halt Normandy Format meetings in a bid to avoid responsibility for its military aggression in the Donbas.

It has been almost a year since the last Normandy Four meeting. Prior to that, the gathering was on standby for three years.

From left: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, French President Emmanuel Macron and Russian President Vladimir Putin arrive for a meeting with German Chancellor at the Elysee Palace, on Dec. 9, 2019 in Paris. The Normandy Four peace talks are dedicated to end the war in Donbas. (AFP)

The next meeting was scheduled to be held in April, but has been constantly delayed, first because of the pandemic and then due to the deadlock in negotiations between Ukraine and Russia.

At the previous meeting in Paris on Dec. 9, 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin insisted that Kyiv should negotiate with the unrecognized, Moscow-controlled authorities in the Donbas directly. His Ukrainian counterpart, Volodymyr Zelensky, refused.

“If you translate the Kremlin’s position into regular human language, it means that no negotiations make any sense unless Ukraine agrees to Moscow’s terms,” Solodkyy said.

“It’s a dead-end. Either Ukraine compromises or Russia,” he added.

Why the talks stalled

Zelensky has limited room for compromise bounded by “red lines” he can’t cross without drawing accusations of selling out Ukraine’s interests.

In the past, Zelensky’s credibility has suffered as the result of failures to clearly communicate proposals related to the Donbas to the public. Controversial appointments and dismissals within the peacemaking group have also provoked the ire of his critics.

After taking office in 2019, Zelensky got off to a good start.

His administration brought 35 high-profile Ukrainian political prisoners and sailors back home and implemented a disengagement of forces near the Stanytsia Luhanska front-line checkpoint. That allowed for the reconstruction of the local bridge, which international observers touted as a major humanitarian victory for the people crossing the contact line every day.

Zelensky’s in-person meeting with Putin in Paris last December did not yield a breakthrough but did result in the release of 135 Ukrainian prisoners.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, bringing other, more urgent issues to the fore.

Besides the unilateral opening of two new checkpoints by Ukraine, little progress has been made in implementing the agreements reached at the Normandy summit.

New locations for the disengagement of forces have not been defined. And the so-called Steinmeier Formula, a peace plan, has not been codified in Ukrainian legislation due to a fundamental disagreement between Ukraine and Russia over what should come first: local elections or border control.

The plan envisions granting self-governing status to the now-occupied territories, but only after Ukraine holds local elections there under its legislation and in presence of the international observers. Kyiv insists it must have control over its eastern border and armed formations must withdraw from the Donbas before the elections can be held.

This requirement remains at the core of Ukraine’s latest peace plan, which was welcomed by Germany and France, according to the Ukrainian President’s Office.

The plan proposed by Russian-backed militant leaders is its polar opposite.

They submitted it in late October after blocking negotiations for three months and demanding that local elections be held on the occupied territories, too.

Despite the absence of a political settlement, the ceasefire that began on July 27 has been held much better than all previous ones, albeit imperfectly.

OSCE monitors recorded a significant drop in violence. In nearly four months, four Ukrainian soldiers have been killed in combat and two civilians have been injured. A little over 2,500 ceasefire violations were recorded as of Nov. 24. In contrast, in the last week before the July 27 ceasefire, monitors recorded 8,000 violations.

Ukrainian border guards stand guard as OSCE observers cross the checkpoint between the Kyiv-controlled territory and occupied areas in the war-torn east, in the town of Schastya in the Lugansk region on Nov. 10, 2020. (AFP)

Katharine Quinn-Judge, a Ukraine analyst for the International Crisis Group, said the sides need to view the security measures not in the context of a broader political solution, but as steps toward alleviating the daily hardships faced by the local population. She cites the pullback and bridge renovation in Stanytsia Luhanska as an example of this approach.

Unfortunately, there are few signs the other side is willing to do this.

Last December, Ukraine expanded the list of goods that can be taken across the contact line and increased weight and value limitations. The Russian side did not reciprocate.

In November, Ukraine opened seven checkpoints, including two new ones, in the towns of Zolote and Shchastya as part of its commitments at the Normandy summit. However, the authorities of the occupied areas have kept their checkpoints closed, using the pandemic as an excuse. In a Nov. 17 report, Human Rights Watch called the restrictions on movement “excessive, confusing, and arbitrary” and said they block civilians’ access to healthcare, pensions and their families.

Currently, there is only one checkpoint open in both directions, Stanytsia Luhanska, and the Olenivka checkpoint on the occupied side is open twice a week.

“Zelensky compromised as much as he could,” Solodkyy said. “Zelensky made so many concessions, but we are not seeing any concessions or compromises on the part of Russia.”

What’s next

Experts agree that the resolution of the Donbas war is in the Kremlin’s hands. As a result, fulfilling the Minsk agreements will be extremely difficult and it is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

“The president (Zelensky) is not a problem. Neither are the negotiators from Ukraine’s side. The problem is not international mediators, either. The problem is Moscow,” Solodkyy said.

“The issue is that the cost of this war is still not prohibitive for Russia,” Quinn-Judge said.

Putin has downplayed the impact of Western sanctions on the country’s economy, saying its counter-sanctions hurt Western countries more. In 2019, Russia reported $6.3 billion in losses from sanctions. At the same time, Russia’s subsidies for the faux states in the Donbas have been estimated at the meager $1 billion to $6 billion a year.

The occupied region is not going to integrate into the Russian economy, but “the republics” hinder Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations.

Nikolaus von Twickel, an analyst and editor at the Center for Liberal Modernity in Berlin, said time is working against Ukraine. The longer those “republics” exist and the anti-Ukrainian propaganda there continues, the less likely it becomes that those who rejected Kyiv will change their minds, he said.

“Ukraine should do its utmost to present itself as a more attractive option than Russia, to become stronger and prosperous,” he said.

However, Ukraine cannot overcome Russia on its own, said Solodkyy.

“Ukraine needs to engage its key Western allies to joint action against Russia’s hybrid war.”