SHAMOKIN, Pennsylvania — The road to Shamokin winds, rises and dips among the high pretty, wooded hills and mountains surrounding it.

For thousands of Ukrainian immigrants seeking a new life in America, the town of 7,000 people in central Pennsylvania was their destination. They would probably have completed the last part of their long journeys by horse-drawn carts after arriving by ship at one of the ports along America’s East Coast and going inland by rail.

The scenery would have reminded them of the hills and mountain ranges of their own home terrain as many of the first immigrants were Lemkos, Boykos, Hutsuls from alpine areas that in modern times lie in western Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia, and Romania.

But the pervasive smell of coal as they approached Shamokin would have been a strange sensation, deep in the heart of coal mining country. As well as traditional pits beneath the earth, the coal was being excavated in massive open cast mines that scraped away huge areas of soil to get the anthracite needed to fuel the process that turned iron ore into steel — the other product that Pennsylvania was contributing to America’s huge economic growth.

Shamokin means “Place of Eels” in the language of the native Susquehanna Indians who lived there prior to the settlers.

It is almost surrounded, belt-like, by a larger community called Coal Township, of some 14,000 people.

Even now, decades after most of the mines closed down, the smell of coal still occasionally wafts in through car windows as a traveler passes what used to be an open cast mine now replanted with grass or trees.

World’s largest manmade mountain

It’s only after speaking to people in Shamokin that the visitor realizes that some of the hills surrounding the town of around 8,000 people were not made by nature but are decades of waste from the mining of anthracite coal.

One became the world’s highest manmade hill, over three kilometers long from 20 million tons of refuse. It overlooks the town and sometimes smoke trails ominously from fires that smolder for decades within its depths.

Nobody knows exactly how many Ukrainians came to work in the coalfields in Shamokin and the many other communities built around mines in the region. But they certainly numbers in the tens of thousands.

The majority of those Ukrainian immigrants had been recruited by agents working for the mine owners sent to Central Europe to find Ukrainians from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Ukrainians, known as Rusyns or Ruthenians at that time, were regarded as more docile than the troublesome Irish miners that had filled most of jobs since the 1830s and who had taken to striking in demand of better wages and conditions.

The fact that, unlike the Irish, few of the Ukrainians spoke any English made them seem easier to keep in line by their employers.

Conditions for miners were dangerous and conditions were tough for their families. There were many fatal accidents as man and huge, powerful machines interacted at a time when safety regulations were sparse.

If a miner died, his wife and children received no compensation and were expected to leave their homes within a few weeks.

Often the widow did not have enough money to pay for a proper funeral and her grief would be compounded by having to bury her husband in a pauper’s grave without even a gravestone.

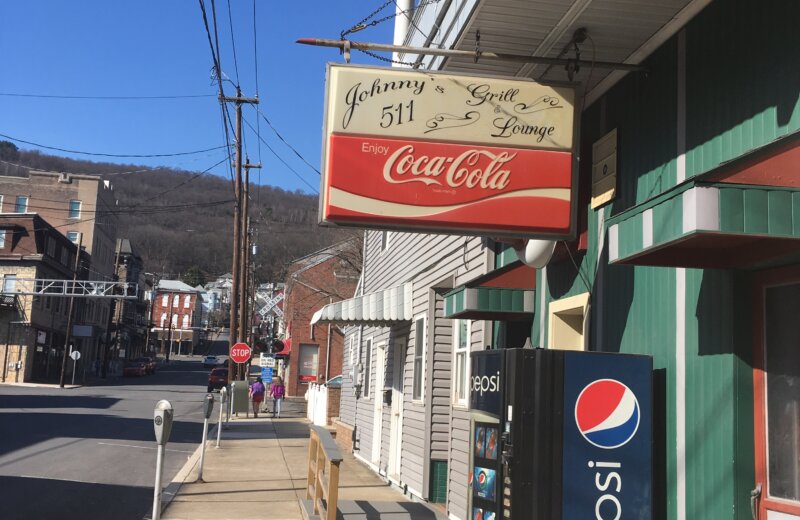

Shamokin, Pennsylvania, is the birthplace of the Ukrainian National Association in 1894. (Photo by Askold Krushelnycky)

An editorial that changed Ukrainian history

An editorial in a Ukrainian-language newspaper in the U.S. called Svoboda (Freedom) had urged in 1893 that Ukrainians organize themselves into self-help groups. The newspaper, which continues today, is rightly proud that it helped change the course of history.

Shamokin was the first place where that call was heeded and on Feb. 22, 1894, a day that was chosen because it was the birthday of America’s founding father, George Washington, the first branch was formed of what would become the Ukrainian National Association.

On May 30, 1894, the association’s first convention to elect a president was held in the town.

The Ukrainian miners mostly belonged to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and had already come together for liturgies in Roman Catholic churches. The first Greek Catholic Parish in the U.S. was created in the nearby town of Shenandoah in 1884.

Wanting a church of their own, they collected donations from their meager wages to build their large church of granite in the style of their homeland with domed copper roofs, now a weathered, oxidized green color.

Father Mykola Ivanov, born in Lviv, studied in Ivano-Frankivsk and Rome and was assigned to Shamokin in 2005.

He said much of the construction work was done by the parishioners themselves, defying exhaustion from long, backbreaking hours in their physically demanding mining jobs to build their superb Transfiguration of Our Lord Church, which was dedicated on Sept. 22, 1889.

Ivanov said: “The parishioners told the architects how they wanted it designed using the influences and styles from the various regions they had come from. These people had a remarkable vision of what they wanted and it was driven by their large hearts which were filled with love for their faith and the Church.”

Keeping Ukrainian traditions

From the 1890s onward, the church and the UNA worked together to build a thriving Ukrainian community with its own schools, and reading rooms.

In 1905, there were some 1,000 parishioners attending church and most were UNA members.

But from the 1960s onward, coal mines started to close down and people moved away to find new jobs elsewhere. Shamokin has a friendly air but it has a worn out feel. Many of the shops are closed and the rows of clapperboard houses have seen better days, like elderly people resigned to never regaining the energy of their youth.

Many of Shamokin’s inhabitants of Ukrainian origin have though clung devotedly to their faith and around 350 attend church services. They nearly all turned out for celebrations when the leadership of the UNA arrived in February to commemorate the founding of the first UNA branch.

There was a special church service and the town’s mayor gave a speech about the importance and contribution to the community of the areas Ukrainian-origin population.

David Kaleta, is a retired teacher at the local high school and he told the Kyiv Post that his family were among the first immigrants who arrived in the late 1800s.

“People are fourth or fifth generation now. Our parents and grandparents used to tell us that as we were in America we should speak English. So very few here now understand or speak Ukrainian,” he said.

The liturgies are all in English but, like most masses celebrated in the Greek Catholic rite, are sung and the distinct melodies and cadences of the Ukrainian-language liturgy are easily recognizable in their English versions.

An old photograph showing an early anniversary of the church has a large portrait of Ukrainian national poet Taras Shevchenko. Today it is likely that many of the parishioners do not know who he was.

Ivanov, who said his primary mission is to cater to the spiritual needs of his congregation, has a cousin who is in the Ukrainian Army and fighting on the front lines in eastern Ukraine against Russia’s invasion.

He tries to make his parishioners aware of Ukraine’s history and the contemporary situation there. Ivanov’s idea is to bring Ukrainians visiting the U.S. to Shamokin so that they can hold discussions and perhaps spark more interest in the “old country.”

He is no doubt inspired by what happened in his church. After all it was here, 125 years ago, that Ukrainian priests and patriots from all over Pennsylvania prayed for success for the self-help group that became invaluable in striving for Ukrainian freedom, the UNA.

During that first, historic convention, what would in 1917 become the Ukrainian national anthem, “Shche Ne Vmerla Ukraina,” was heard for the first time in America, performed by local choirs.