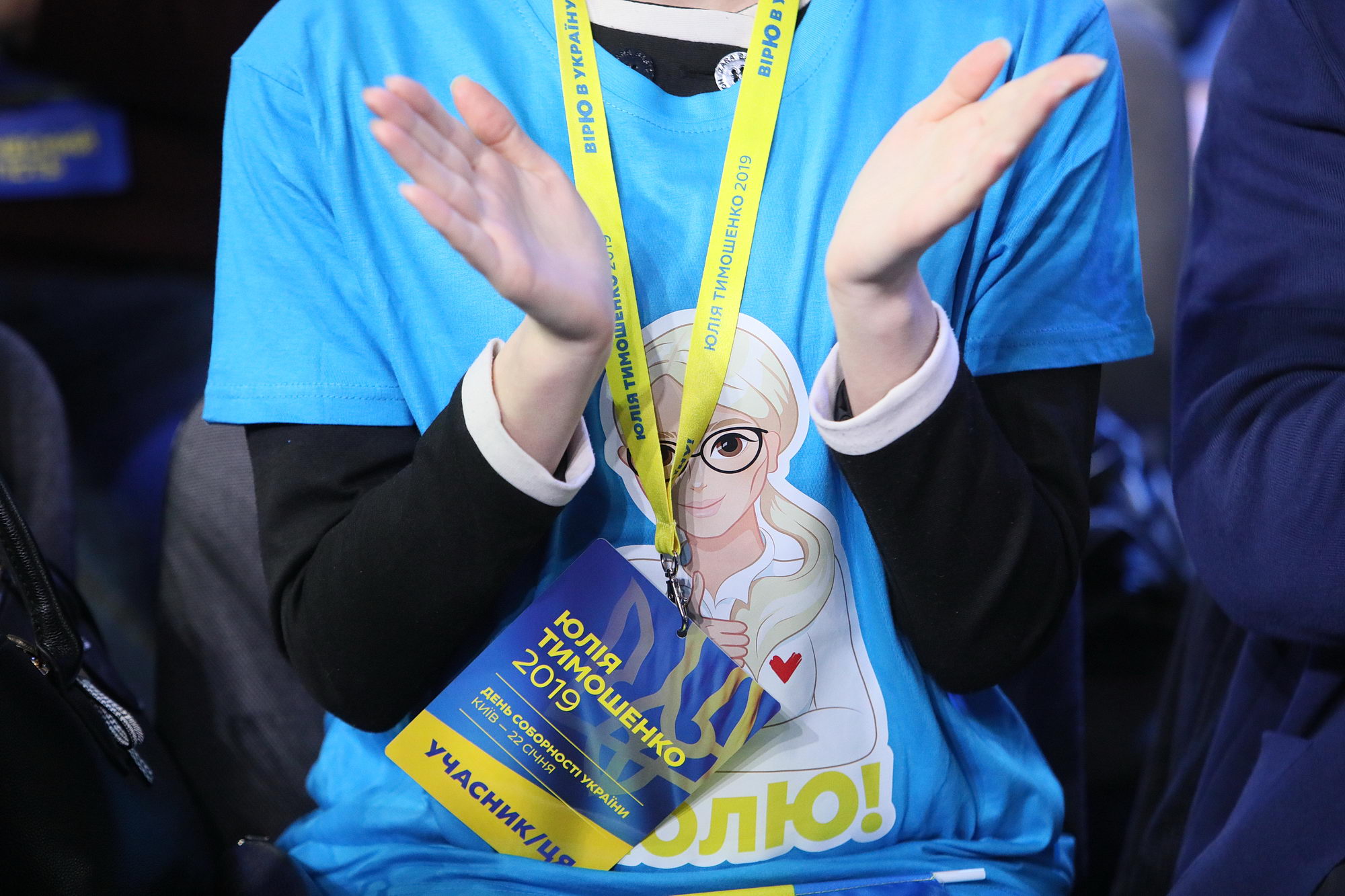

Former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko wasn’t stingy when organizing her party congress on Jan. 22, the meeting which officially nominated her to run for presidential election in March.

She invited the members of her Batkivshchyna party, which currently holds just 21 seats in parliament, to one of the capital’s prime venues, Palats Sportu, the centrally located Soviet event hall. They were almost enough to fill the 10,000-seat venue.

She entertained them with a high-quality show, music performances, and videos about Ukraine’s history and Tymoshenko’s political past.

The forum, held on Ukraine’s Unity Day, was full of symbolic messages, opening with a prayer for Ukraine led by prominent church leader Patriarch Filaret, and Ukraine’s first president Leonid Kravchuk. The Ukrainian national anthem was performed by a little girl with hair braided in the style that Tymoshenko had worn for many years.

So now it’s official: On March 31, Tymoshenko, a populistic opposition leader who’s been in the top echelon of Ukrainian politics for 20 years, will try for the third time to become president, after unsuccessful attempts in 2010 and 2014.

Leading in all recent polls with ratings of about 20 percent, Tymoshenko’s chance of winning the presidency are higher than ever.

Her weak side, however, is her anti-rating of about 26-27 percent in December, as recorded in various polls, which exceeds her popularity rating – more voters dislike her than like her.

While her supporters praise her for creativity and hard work, for many in the nation Tymoshenko, a former gas dealer who started her political career back in 1997, symbolizes the old corrupt political elite.

Breaking stereotypes?

Speaking during the congress, Tymoshenko, who wore a red dress and her usual high-heel shoes, tried to show her softer side. She spoke about her family, the tough times she spent in prison, jailed by the regime of ousted former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, and about being betrayed by some of her former friends.

“I made mistakes,” she said. “I’m human, just like you are.”

It was a contrast with her usual tough rhetoric. Then she promised change – as she has done many times during her long political career.

“If in the first 100 days in presidential office I can’t break the old system, can’t show you any results, I’ll just leave the presidential post,” Tymoshenko said.

The audience applauded her – at the direction of rally ushers, male ones dressed in blue, and female ones in yellow. The same ushers indicated to the audience when they should wave their little blue-and-yellow national flags.

Answering Poroshenko

Much of Tymoshenko’s speech was directed at her current main rival, incumbent President Petro Poroshenko, whose team has branded Tymoshenko a pro-Russian politician.

“Calling opponents a ‘hand of the Kremlin’ is the main political technique used by those in power during current elections,” she said.

To undermine Poroshenko’s image as of main defender of the army, Tymoshenko invited to the stage dozens of veterans of Russia’s war against Ukraine, whom as she said had defended Donetsk airport in 2014-2015, one of the most dramatic parts of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

One veteran read a poem in honor of Tymoshenko, calling her “the only political cyborg of Ukraine,” making a reference to the nickname “cyborgs” that the Ukrainian defenders of Donetsk airport got for their endurance.

Tymoshenko also repeated a common accusation against Poroshenko voiced by his opponents – that he tries to profit from the war, selling low-quality military equipment produced by his businesses to the military. She promised not to do the same.

She also tried to play down what Poroshenko now sees as his main achievement in office — obtaining a tomos of autocephaly, or a decree of independence, for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. But while Patriarch Filaret, the former leader of the unrecognized Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate, opened the congress with a prayer to script, he appeared to go off message later by thanking Poroshenko for securing the tomos for Ukraine, which seemed to surprise the audience.

Where does the money come from?

Tymoshenko, as she has done many times before, promised to fight corruption and rid Ukraine of oligarchs. But the extravagant event she was presiding over reflected not only the massive number of Tymoshenko supporters, but also the massive resources she appears to have at her disposal.

Reformist lawmaker Sergii Leshchenko wrote on his Telegram channel that the no-expense-spared show was a signal that oligarchs are already sponsoring Tymoshenko’s campaign.

Tymoshenko started campaigning more than a year ago, earlier than all other candidates, hanging her billboards all over the country. But until she hasn’t registered as a candidate she was not obliged to account for all campaign spending. While election observers call this a violation, Tymoshenko’s media consultant Oleksiy Mustafin said before registration as a presidential candidate she was campaigning as Batkivshchyna party leader, and the money for the campaign came from party funds.

Change of strategy

Tymoshenko’s rating started rising since 2016 when she became a vehement critic of the hike in utility tariffs that the government had to agree to maintain cooperation with the International Monetary Fund. Tymoshenko at the time called it “tariff genocide,” and won popularity predominantly among the residents of small cities and villages all over Ukraine – those worst affected by the hike.

In summer, she also launched a rebranding of her campaign, holding four big forums in Kyiv, where she spoke about her new vision for the country. Her radical proposals to rewrite the country’s Constitution and use of words like “blockchain” were supposed to help her win new supporters among younger residents of the big cities.

With little to show for that tactic, Tymoshenko has since returned to her usual strategy and usual electorate, promising to cut household gas bills in half.

Most of the visitors to her congress on Jan. 22 were middle-aged. Many have been devoted followers for more than a decade. At the same time, now she’s the presidential candidate with the most precise program, political analyst Volodymyr Fesenko said.

And the party faithful believe it.

“This person has a team and a vision for Ukraine,” said one congress attendee, Tetiana Azirina, 65, who has been a member of Tymoshenko’s party since 2006.