President Volodymyr Zelensky began his presidency with an important message: Ukraine will support people of Ukrainian heritage’s return to their motherland.

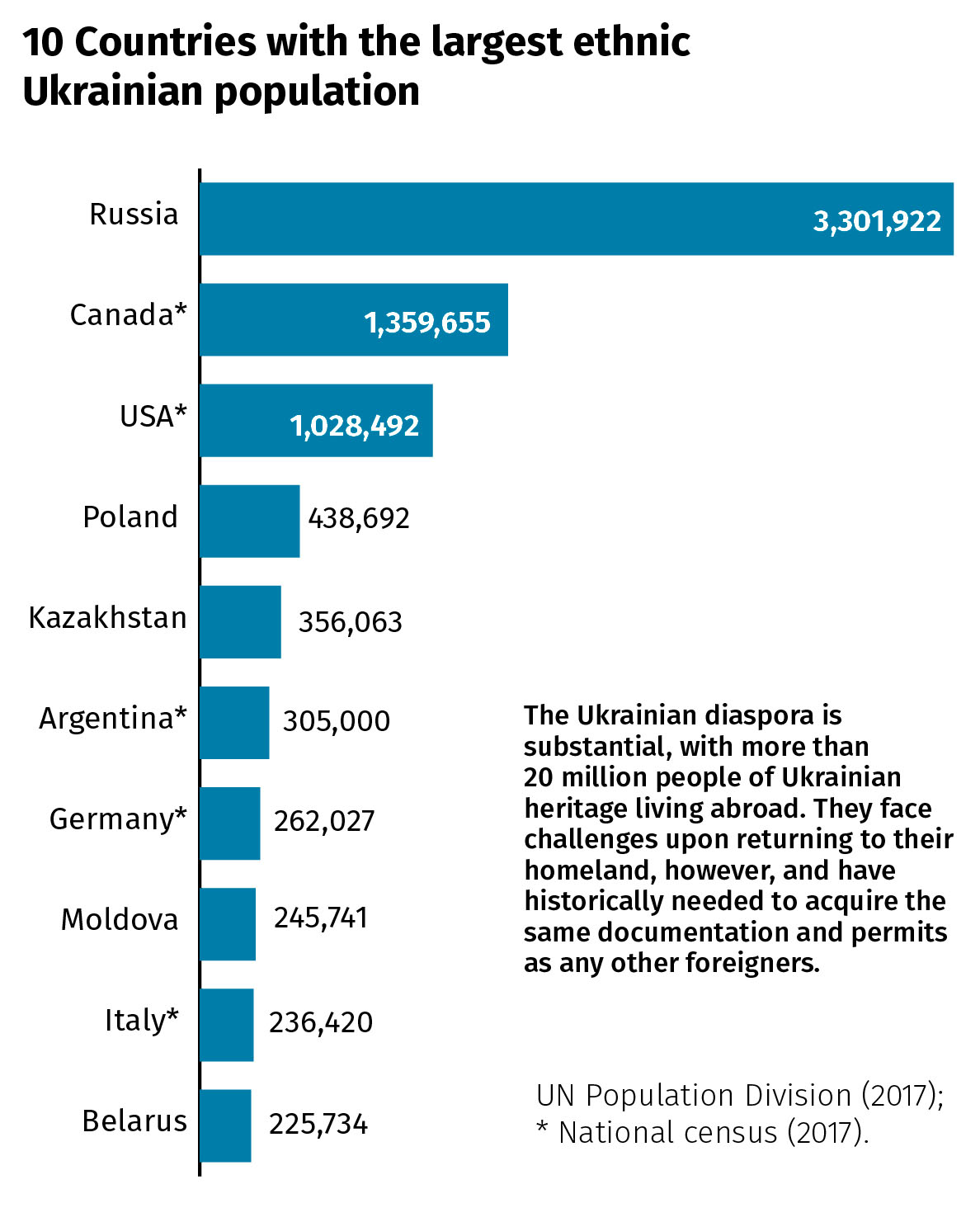

“I appeal to all Ukrainians on the planet: we really need you,” Zelensky said during his inauguration on May 20, adding that there are more than 20 million Ukrainians living elsewhere.

However, Ukraine does not permit dual citizenship. That means the president must now create mechanisms to accommodate foreign Ukrainians who want to work and study in Ukraine while keeping their primary citizenship.

In 2004, Ukraine took the first step toward accommodating foreign nationals with ties to Ukraine by creating the Foreign Ukrainian card. The card is issued by a special commission to members of the Ukrainian diaspora who can prove their Ukrainian heritage.

The card gives them the right to work and study in Ukraine without having to renounce their primary citizenship. But it largely swims under the radar, and often Ukrainian state officials have no clue that the card exists.

And that’s a problem, according to several experts.

Ukraine must promote the Foreign Ukrainian card, grant it more power and create an effective mechanism for making the card appealing to members of the Ukrainian diaspora willing to work and do business in Ukraine.

This isn’t a new idea. Since 2007, Poland has created a mechanism to extend many of the rights of Polish citizenship to members of the Polish diaspora. So why can’t Ukraine?

Passport wars

The idea of granting citizenship to those of Ukrainian heritage dates back to the days of Ukrainian independence.

After three major waves of emigration across the 18–19 centuries, an estimated 6 to 20 million people of Ukrainian ancestry are scattered around the globe.

During his inauguration speech, Zelensky promised to simplify the procedure to give out Ukrainian passports to the diaspora.

“To all who are ready to build a strong and successful Ukraine, I will gladly grant Ukrainian citizenship,” Zelensky said.

Yet, the main concern of those obtaining Ukrainian citizenship is that they forfeit their primary citizenship.

According to the constitution, Ukraine doesn’t recognize dual citizenship. If a Ukrainian national obtains a foreign passport, he or she still is considered a Ukrainian citizen in Ukraine. However, if a foreigner wants to obtain a Ukrainian passport, he must renounce his other citizenship.

Members of the Ukrainian diaspora, mainly concentrated in North America and the European Union, won’t give up their citizenship rights in their home countries to become Ukrainian nationals.

Paul Grod, head of the Ukrainian World Congress, believes that Ukraine must introduce dual citizenship for Ukrainians abroad.

“Ethnic Ukrainians, provided they meet reasonable criteria for citizenship, should be eligible to acquire Ukrainian citizenship without the need to renounce their current citizenship,” says Grod.

However, Ukraine is hesitant to allow dual citizenship. The government fears that more and more Ukrainians will be granted Russian citizenship, which will help Russia justify a further invasion of Ukrainian territory.

In March 2014, Russia used “protecting” its citizens as a pretext for war against Ukraine.

On April 24 of this year, Russian president Vladimir Putin simplified the procedure for obtaining Russian citizenship for those living in occupied regions of Donbas. Two months later, the simplification was expanded to all residents of Ukraine’s Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts.

Now Ukraine has gone on the offensive, promising Ukrainian citizenship to Russians facing politically motivated persecution back home. They would need to renounce their primary citizenship.

However, an exclusion must be made for Ukrainians living in the West.

“Some may want the full privileges and responsibilities of citizenship, yet others may prefer a more robust status of Foreign Ukrainian which currently exists but has very little value,” says Grod.

Despite modest improvements, many foreigners in Ukraine are still facing an uphill battle to obtain their visa and documents.

Foreign Ukrainian

For Ukrainians who were born outside Ukraine but want to have the option of living and working in Ukraine, there is an option that allows them to keep their initial citizenship.

Foreign Ukrainian status is issued to those able to prove their Ukrainian ethnicity or that their ancestors lived on the territory of present-day Ukraine.

On paper, the card grants an abundance of rights — the right to study for free in Ukrainian universities, work in Ukraine and obtain a long-term tourist visa, if needed.

A commission headed by Ukraine’s foreign minister gathers four times a year to review applications.

However, as of 2018, only 10,322 people have received the Foreign Ukrainian status.

Pavlo Kravchuk, an expert at Europe without Barriers, a nonprofit studying migration, says that few in Ukraine know that the Foreign Ukrainian card exists — and that includes government officials who, in theory, must provide services to card holders.

“They ask: ‘What is it? What does it do?’” says Kravchuk.

The main problem is that, even though the card provides many services, including the right to work and to study for free, these rights exist only on paper.

“Those who obtained the card expected something, yet they didn’t receive what they expected,” Kravchuk says.

The card also provides a 5-year tourist visa, but most members of the Ukrainian diaspora already live in visa-free countries. Thus, they can easily visit Ukraine for 90 days every 180 days. The card also doesn’t simplify the process of obtaining Ukrainian citizenship.

Polish example

In 2007, the Polish government introduced the Polish Card, issued to citizens of the former Soviet Union who can prove their Polish ancestry.

The card gives them the right to study for free in Polish schools and universities, open businesses and work in the country without a work permit. The card also provides financial assistance from the state to those in need and simplifies the process of obtaining Polish citizenship.

The card has been crucial for boosting Poland’s workforce. According to Ukrinform news agency, over 200,000 people received the Polish Card in the first 10 years of its existence, among them over 105,000 Ukrainian nationals. Over 10,000 people apply for the card yearly.

Ukrainians and Belarusians are the primary recipients of the card, mostly young people seeking the chance to work and study in the European Union.

There is a clear advantage to receiving the Polish Card, says Kravchuk.

Poland has higher wages and needs labor. The country is also a member of the European Union, and Poland’s passport has more power, allowing its holders to work and travel to more places.

According to the World Bank, Poland and Ukraine have among the lowest fertility rates in the world, yet Poland has been able to maintain its population due to an influx of migrants.

In contrast, Ukraine’s population declined from 53 million to a mere 42 million since obtaining statehood.

In 2019, the Polish government opened the Polish Card to members of the Polish diaspora worldwide.

The so-called Polish Card is offered by the country to people of Polish national heritage who live abroad (diaspora) and grants them the right to live, work and study in Poland.

Introduced in 2007, it has proven 20 times more popular than a similar card issued by Ukraine, called a Foreign Ukrainian Card. The permit offered by Ukraine is considered more difficult to obtain and does not offer a pathway to eventual citizenship.

Catching up

But change may be coming. After his election, Zelensky expressed his intention to make it easier for those who associate themselves with Ukraine to live and work in the country. The success of the Polish Card can serve as an example.

Ukraine can’t compete with Poland in terms of wages, but the document can serve as a working mechanism for those willing to do business in Ukraine.

The Foreign Ukrainian card gives almost the same rights as its Polish counterpart, but has been neglected for years.

“First we have to inform the people,” says Kravchuk.

Those services written in the law must be delivered. Government officials must know their responsibilities, and potential recipients of these services must know their rights.

The government should promote the card by increasing its benefits — for example, fast-track citizenship, the right to live in Ukraine without a visa, the right to open a business, and access to bank loans and tax breaks.

However, many are hoping for Ukraine to introduce dual citizenship, albeit with strict restrictions on who can hold two passports. The Ukrainian World Congress wants its members to be allowed a Ukrainian passport with voting rights and the option to service the country both in the military and the government. But it’s president also supports the Foreign Ukrainian card.

“I believe that both options should be available to ethnic Ukrainians,” he says.